Breaking with the past: how voting reform could reinvigorate Australian politics

Spoiled ballot papers and the lowest turnout since voting became compulsory in 1925: young Australians are increasingly disillusioned with traditional politics, and with the two main parties in particular. Adele Lausberg says it is time to overhaul the way the House of Representatives is elected to give smaller parties more of a voice. Both the House and the Senate would benefit from a shake-up in their seating arrangements to foster a more consensual approach.

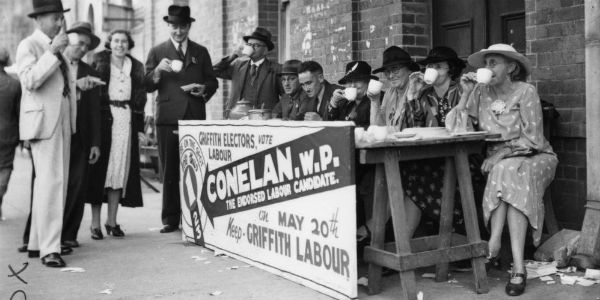

More enthusiastic times: campaign workers take a tea break during elections in Brisbane in 1939. Photo: State Library of Queensland. No known copyright restrictions

Young people in Australia are increasingly becoming disinterested and disengaged from mainstream electoral politics. While this trend cannot yet be classified as long term, it raises an interesting point of why young people are turning away from traditional conceptions of politics, and why they are less likely than older Australians to join political parties.

This is not just a problem affecting the young. Research demonstrates that there is waning interest in politics from Australian citizens, with a 2014 poll showing only 43 per cent of Australians think that it matters which major party is in power. The 2016 election saw a rise in the ‘other’ vote in both the House of Representatives and the Senate, a steady increase that has occurred since the 2010 election. In 2013, first preferences for parties in the House of Representatives other than the two major parties reached 21.1%, eclipsing the 1998 record of 20.4% while in the Senate the record reached 32.3%, up from 26.2% in the 2010 election (see here for records since 1949).

Given the increase in the vote of the ‘other’ parties and the increasing propensity for young people to cast an intentional informal vote, perhaps it is time to consider more radical change to give voters more options in who represents their interests outside the two major parties. While the current upward trend in ‘other’ votes may be cyclical, if it continues into the long-term the current system may warrant reform.

A change in voting system is not fanciful

An overhaul of a political system is not a fanciful idea. In 1996, New Zealand changed from a first-past-the-post system to a mixed-member proportional system. Voters in New Zealand were given the opportunity to use a referendum to overhaul their system, punishing the major parties and ushering in electoral change. They chose the Mixed Member Proportional system, transforming New Zealand politics in one stroke.

Changes to Australian voting systems are not without precedent either, with examples in both 1984 and 2016. One significant criticism of the Senate’s electoral system in recent years was the allocation of preferences by parties. The ability of the Australian Motoring Enthusiast Party to gain a Senate seat with only 0.51% of the Victorian vote was of considerable concern to voters and commentators alike. That our political system was able to give an individual micro-party such power was indicative of problems with the Senate voting system. The reforms passed in a marathon sitting in 2016 introduced optional preferential voting and abolished group tickets which were the root cause of this problem. Though they have not yet been tested at a half Senate election yet, the reforms did not reduce the number of smaller parties at the double dissolution election in 2016 and there are now 20 cross bench senators. This is the largest crossbench since the expansion of the Senate in 1950, allowing for a considerable variety of representatives, arguably better reflecting the views of voters.

The Senate has been home to more diverse parties and individuals that reflect a wider representation of the Australian community – for better or worse. It is likely that the Senate will continue to offer a more diverse representation of parties and political issues into the future. The ability of Australians to elect a wider array of political parties to the Senate is made possible by the proportional voting system in that house. By contrast, the House of Representatives has single members for each electorate, elected through a full preferential voting system. This leaves a considerable number of voters feeling under-represented by their local member. For example, The Greens gained 10.2 per cent of the nation-wide vote in the House of Representatives in 2016, yet this translated to only one seat in that House. At the same time, they received 8.7 per cent of the vote in the Senate and were able to secure 9 seats.

We can already see different voting systems in action across Australian parliaments, with Hare-Clark in Canberra and Tasmania. While all electoral systems have flaws and none can offer a ‘perfect’ solution, having a higher number of political parties allows for wider representation of the community’s views and could mean more voters feel that their vote counts, which may help engage younger voters. It also allows more space for minor and peripheral parties to collaborate with members of major parties to achieve legislative change.

Reforming the House of Representatives and Senate

Reform in the House of Representatives could follow the Hare-Clark model, expanding the geographical size of electorates and increasing the number of representatives elected to each. In order to accommodate this new system, the ergonomics of the chamber could be rearranged in a semi-circle with all members facing the speaker’s chair, following the Riksdag (Swedish parliament). Members of the Riksdag are arranged by region, not party, which creates more opportunities for cooperation across party lines, albeit by region-specific issues more than community issues.

This same seating model could be translated to the Senate, which would help return the Senate to one of its original functions as a state’s house. While the voting system in the Senate already allows for greater diversity in parties, it has been argued that further reforms could be made to more accurately reflect the numerical population of the states, as well as introducing reserved seats for indigenous Australians.

If momentum for adapting Australia into a Republic is reinvigorated, this could create an opportunity to have a national conversation about changing our electoral and political systems. Undeniably, wholesale change would be incredibly difficult to achieve, not least because it would involve major parties disadvantaging themselves and there is a historical difficulty in passing referenda. However, New Zealand demonstrates that this is not an impossible feat.

The last three elections have shown that votes are increasingly going to ‘other’ parties which — if it indeed continues — should make us pause and reflect. A more serious concern is voters reporting that they do not care which party is in power. Australians overall have shown they enjoy the act and empowerment of voting – we consistently generate high proportions of unspoiled votes. Yet we must recognise that more young Australians are beginning to intentionally spoil their ballots in recent elections as a form of protest. It is important to foster political interest and engagement in our youth. If the current trends continue, it may be time to discuss opportunities for systemic reform.

This post represents the views of the author and not those of Democratic Audit. It first appeared at PopPoliticsAus.

Adele Lausberg is a PhD candidate at the University of Adelaide.

Adele Lausberg is a PhD candidate at the University of Adelaide.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Again, though, tinkering with the seating arrangements (making them in a cosy circle rather than the old way) is not the answer to the failure of the political elite to engage the younger voter – it actually sounds like a perfect version of the old analogy…of re-arranging the deckchairs of the Titanic as the ship goes down.

The real answer is that the political class has failed to respond to changes and specifically appears to want to both patronise the voter and tell them what they want to hear and then do the opposite (why on earth is Hollande so unpopular in France? Elected as a left winger and then immediately puts into force rules and laws at the behest of his real masters in Berlin and Brussels). Fine if you’re a full-on austerity supporter and a member of the Goldman Sachs fan club, but not what the voters went into the polling stations for. Same with Syriza in Greece.

We can mess around with the type of chairs, or the systems all we like but if the entire elite continues to let the voter down while appearing to hate them, well there is little hope. The problem starts there, not with those naughty chairs.

Breaking with the past: how voting reform could reinvigorate Australian politics https://t.co/FadZzZ60yj

Breaking with the past: how voting reform could reinvigorate Australian politics https://t.co/ovKDZ5KniW https://t.co/qParMVR16K