Auditing the UK’s democracy in 2018: Core UK governance institutions show sharply declining efficacy

Today we are publishing The UK’s Changing Democracy: The 2018 Democratic Audit, a systematic assessment of the country’s democratic institutions, large and small. Previous audits of the UK’s democracy, including the most recent in 2012, have generally found that, overall, the quality of our democratic institutions have improved over the past twenty years. However, Patrick Dunleavy and Alice Park find that this year’s Audit shows unprecedented declines in the core institutions of the UK’s democratic system, particularly at the centre.

The context

The 2018 Democratic Audit presents the most comprehensive survey of recent trends across all aspects of the UK political system. Carefully assessing liberal democratic trends within the UK has never been so important in recent times because:

- From April 2019 the UK government will cut loose completely from the convergence on a ‘European’ template for liberal democracy, which has previously dominated most recent constitutional and political changes since 1997.

- The UK’s famously ‘uncodified’ (or messy) constitution faces another period of dramatic upheaval.

- New loads will be placed on the UK central government by ‘taking back control’ of trade policy and immigration. Steering a single-country course is more difficult also within a world economy and system of international relations that is increasingly dominated by giant nation states (China, USA, India) and the EU, and where realpolitik ‘power politics’ seems to be renascent (as with Russian policies).

- The background international context for liberal democracies has also worsened dramatically:

- Some iconic liberal democracies (like the USA) are now backsliding on respecting democratic basics, such as maintaining the integrity of elections.

- More recent liberal democracies have slipped back into semi-democracies where incumbents skew the scales of elections in their favour and penalise political opponents (as in Turkey, Thailand and the Philippines).

- Even within the EU powerful populist incumbents are skewing constitutional arrangements in their favour (for example, in Hungary and Poland), while elsewhere corruption remains a serious threat.

- Established semi-democracies have become more authoritarian and locked-in over time, with breaches of rights and overseas excesses increasing (as in Russia).

- China continues to demonstrate that an authoritarian government can post remarkable economic growth and maintain relatively stable governance, and at immense scale – undermining liberal democracy’s claim to uniquely support economic modernisation and social development.

- Some evidence suggests that Western publics have increasingly lost sight of, or mentally downgraded, the importance of living in a democracy.

- Recent experience demonstrates that having a few big ‘building blocks’ of democracy in place, such as a majority voting system and a popularly elected legislature, is not enough to prevent democratic decay or backsliding. In addition, dozens of ‘micro-institutions’ must also work in pro-democratic and supportive ways if an overall level of responsiveness to majority views and protection of civil liberties is to be maintained.

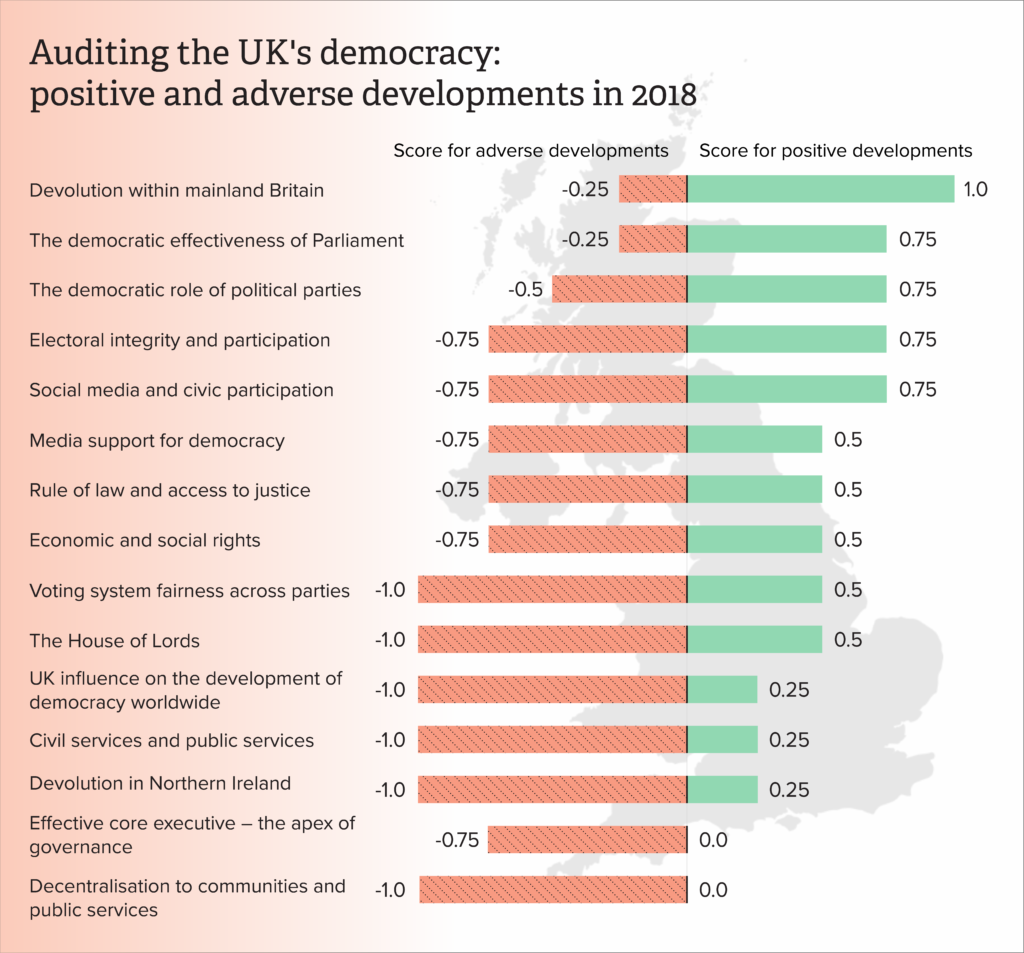

Notes: Each score indicates the answer to the questions: ‘Have positive and substantial pro-democratisation trends occurred?’ (for positive scores); or ‘Have substantial threats or problems to democratic quality emerged in this area?’ (for negative scores). 1 = clearly Yes to the question posed; 0.75 = tending towards Yes; 0.5 = impossible to say Yes or No to the question; 0.25 = tending towards No; 0 = Clearly No to the question posed.

Source: Scores from The UK’s Changing Democracy, Chapter 8.1: The UK’s recent democratic gains and losses. Infographic by Stacey McCormack.

The key causes for concern

We find seriously worrying adverse changes in the democratic quality of some core political processes in the UK:

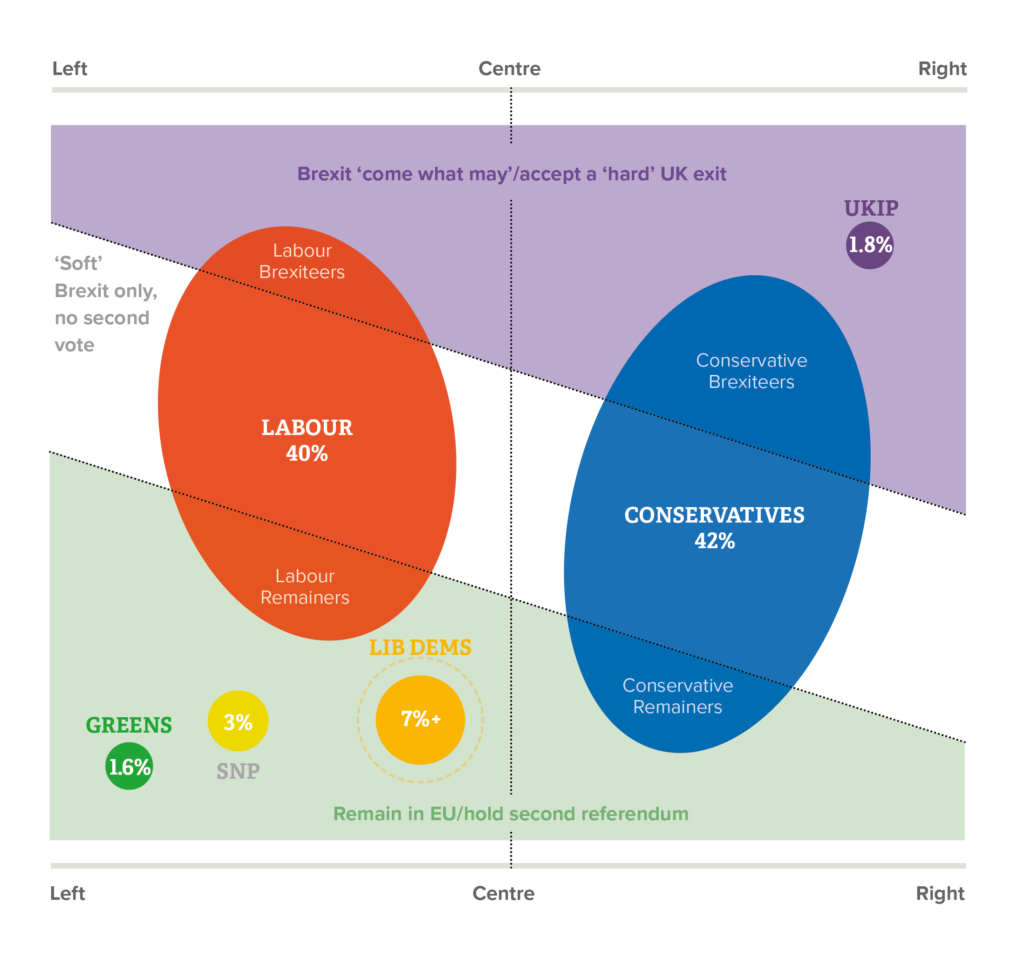

- British party politics is in an unprecedentedly chaotic condition. Divisions over Brexit cross-cut the top two Conservative and Labour parties (see Figure 1, below), and the two parties’ leaderships have proved unable to develop any effective consensus on the UK’s strategy. The attempt to force through only a governing-party solution for leaving the European Union (forswearing any national consensus, especially Conservative–Labour co-operation) has created protracted uncertainty, depressed economic growth, and cost households and enterprises dear.

- Meanwhile in England the smaller parties (Liberal Democrats and UKIP) are locked into seriously adverse positions by their own recent records and decisions.

- Systems for internal party democracy allowing wider party memberships to elect party leaders are theoretically in place. But they were by-passed by Conservative elites in 2016, so that Theresa May became Prime Minister without any contest. They have also failed in the Liberal Democrats since 2015 (because there are too few MPs to sustain a competition). And in 2015 many Labour MPs proved unable to accept the election of Jeremy Corbyn, or work with him, despite his convincing win, rerunning the contest in 2016, and only really reconciling to his leadership in spring 2017.

Figure 1: The UK’s changed party system at the 2017 general election and the subsequent Brexit negotiations phase

Notes: The positions of the party ovals show their approximate left/right position; their size shows their vote shares at the 2017 general election; and their shape shows how party opinion spreads across the green, white or purple Brexit positions shown. (The Liberal Democrats’ dotted line shows their stronger local election performance.)

Notes: The positions of the party ovals show their approximate left/right position; their size shows their vote shares at the 2017 general election; and their shape shows how party opinion spreads across the green, white or purple Brexit positions shown. (The Liberal Democrats’ dotted line shows their stronger local election performance.)

Source: From The UK’s Changing Democracy, Chapter 3.1: The political parties and party system (Figure 2).

- The cumulative adverse impacts of austerity and non-growth policies (2010–18) on core executive capabilities, the civil service, public services and local government have rapidly increased since 2015. Civil service efficacy has radically declined, the quality of public services has significantly worsened, and local government has been hollowed out.

- The once smoothly operating central government apparatus around the Prime Minister, Cabinet and major departments has stuttered and malfunctioned with increasing frequency – generating policy disasters over Iraq, Afghanistan, Libya and Brexit in foreign affairs, and in the domestic realm over NHS reorganisation (2010–12), Universal Credit (2011–18) and the complete erosion of building safety regulations that became evident in the Grenfell Tower catastrophe.

- UK democracy is still limited by legacy arrangements from imperial or pre-democratic times that should have no place in a modern liberal democracy, including:

- A completely unelected second chamber of the legislature, with no accountability to citizens at all.

- An extensive ‘dark state’ apparatus, subject to no or only vestigial overview by Parliament or democratic institutions.

- An unclear residue of ‘crown prerogative’ powers for government to take major executive actions alone, without parliamentary approval, for example on declaring war, launching military actions or incorporating former EU-era regulations into UK law.

- A main electoral system for Westminster and English and Welsh council elections that dates from mediaeval times and erratically assigns parties seats in no fixed relation to their share of votes – for example, giving the SNP 95% of Scottish seats at the 2015 general election, on the basis of winning 50% of votes.

- The complex power-sharing devolution arrangements in Northern Ireland have ceased to operate, jeopardising its future governance at a key time.

- Even in areas where the UK has previously led good practice, democratic effectiveness has been undermined by a failure to recognise new threats and challenges. For instance, electoral integrity in the UK is normally high, but out-of-date legislation and regulation failed to properly regulate Leave spending in the 2016 referendum, prevent Russian bots influencing voters in 2016 and 2017, or curb manipulative messaging and targeting of voters using illegitimate information.

Optimistic developments

Not all recent developments are gloomy though. Hopeful changes in UK democracy, include:

- Since 2010 Westminster has been a ‘hung parliament’ for all but two years (2015–17), instead of a single party having a controlling majority. This has increased backbench MPs’ roles in policy-making on some major policy issues, and made the select committee system increasingly effective in overseeing policy implementation.

- Mass party memberships have re-grown in the digital era, at least in Corbyn’s Labour Party and the Scottish National Party, and have helped to diversify these parties’ sources of finance.

- Devolution in Scotland and Wales has proved increasingly successful, attracting involvement by voters, developing distinct national party systems and producing effective governments, whose powers have also grown strongly over time, and should expand further after Brexit.

- Positive and responsible uses of social media by most citizens (on a scale far larger than abuses of social media) have greatly extended the scope and quality of public surveillance over governing elites. Ordinary people can now make their views heard on far more issues, in specific detail, and far more quickly and effectively – increasing the responsiveness of officials and public services to public opinion.

The UK’s Changing Democracy: The 2018 Democratic Audit is published by LSE Press on 1 November 2018. This article is based on the executive summary.

Patrick Dunleavy is Professor of Political Science and Public Policy at the London School of Economics, and Centenary Professor at the University of Canberra. He is co-editor of The UK’S Changing Democracy (LSE Press, 2018), published free and open access on 1 November.

Alice Park is Managing Editor of the Democratic Audit blog and co-editor of The UK’s Changing Democracy.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.