How democratic and effective are the UK’s civil service and public services management systems?

Citizens and civil society have most contact with the administrative apparatus of the UK state, whose operations can powerfully condition life chances and experiences. In an article from our forthcoming book, The UK’s Changing Democracy: The 2018 Democratic Audit, Patrick Dunleavy considers the responsiveness of traditionally dominant civil service headquartered in Whitehall, and the wider administration of key public services, notably the NHS, policing and other administrations in England. Are public managers at all levels of the UK and England accountable enough to citizens, public opinion and elected representatives and legislatures? And how representative of, and in touch with, modern Britain are public bureaucracies?

Whitehall sign. Picture: Can Pac Swire, via a (CC BY-NC 2.0) licence

Whitehall sign. Picture: Can Pac Swire, via a (CC BY-NC 2.0) licence

What does democracy require for how Whitehall and the national civil service operates, along with wider public service delivery systems?

- Services provision and implementation, and the regulation of social and economic activities, should be controlled by democratically elected officials so far as possible. Policy-making at this level should be deliberative, carefully considering all the interests of all relevant actors.

- Before significant policy or implementation changes are made, fair and equal consultation arrangements should allow service recipients and other stakeholders to make inputs into decisions, especially where services are being withdrawn or rights are being constrained.

- The management of all public services at all levels of government (within national, regional, local and micro-local agencies) should be impartially conducted within administrators’ legally available powers. All citizens should have full and equal access to government and to the beneficial services and goods to which they are entitled, without discriminatory provisions applying to any group. The human rights of all citizens should be carefully protected in decision-making, and ‘due process’ rules followed in adjudicating their cases or entitlements.

- Wherever ‘para-state’ organisations deliver services on behalf of or subsidised by government (for example, non-government organisations [NGOs] or private contractors), these public value standards (action within the law, equal treatment and access, respect for human rights, and freedom from corruption) should all apply in exactly the same way.

- The importance of ‘public value’ considerations is especially heightened in government legal and regulatory activities, cases of compulsory consumption, where service-users face any form of ‘coerced exchange’ choices, or where consumers depend heavily on professional expertise or are subject to the exercise of state or professional power.

- Public services, contracting and regulation should be completely free from corruption, with swift action taken against evidence of possible offences.

- The civil service and public services organisations should recruit and promote staff on merit, having due regard for the need to combat wider societal discrimination that may exist on grounds of race, ethnicity, gender, disability or other factors.

- Ideally, public administrations will be ‘representative bureaucracies’ whose social make-up reflects (as far as possible) that of the populations they are serving. Where differences in the social make-up of the people delivering and receiving public service has significant implications for the understanding, legitimacy and perceived quality of services, the delivery organisation must demonstrate committed efforts to overcome recruitment biases.

- Government-organised and -subsidised services should be efficient and deliver ‘value for money’. Costs should be reasonable and competitive, and the activities and outputs should be produced using technologies that are modern, and kept under review, using best practice methods. Over time the productivity of government-organised and state-subsidised services should grow, ideally at or above the societal average level.

- The efficacy of government interventions and regulations should be carefully assessed in a balanced and evidence-based way, allowing for consultation not just with organised stakeholders but also with unorganised sets of people affected, or interest groups active on their behalf.

- Regulation and de-regulation should both be implemented in balanced, up-to-date and precautionary ways that safeguard public safety and the public interest, but keep the economic and transaction costs of regulation to the minimum needed.

- Point of service standards in the public services should keep pace with and be comparable to those in other modern sectors. Procedures for complaints and citizen redress should be easy to access and use, and public service delivery agencies should operate them in transparent and responsive ways, fulfilling ‘freedom of information’ requirements.

- Where mistakes happen, and especially where public service delivery disasters occur (at implementation levels) that seriously harm one or a few persons, or that affect large number of people in highly adverse ways, public service organisations should show a committed approach to recognising and rectifying problems, and to rapid organisational learning to prevent them from recurring.

In liberal democracies, citizens and politicians expect that the civil service and other public service organisations will meet all of the multiple requirements listed above, simultaneously. If lapses occur in any aspect, public trust in these bodies can be severely impaired, usually increasing their costs appreciably and reducing their abilities to get things done.

Yet the different expectations clearly crosscut each other. For instance, carefully consulting and respecting human rights adds expense and time to government agencies’ processes, so it may curtail their ability to reform, and impair efficiency-seeking and cost containment. Similarly, treating people equally means that agencies cannot do what firms do, and focus just on those customers who are easy or profitable to serve, turning their backs on difficult cases. Yet agencies are also expected to match firms in terms of productivity growth. Public management involves handling these dilemmas so as to (somehow) steer a course between them that maximises public value.

Yet the different expectations clearly crosscut each other. For instance, carefully consulting and respecting human rights adds expense and time to government agencies’ processes, so it may curtail their ability to reform, and impair efficiency-seeking and cost containment. Similarly, treating people equally means that agencies cannot do what firms do, and focus just on those customers who are easy or profitable to serve, turning their backs on difficult cases. Yet agencies are also expected to match firms in terms of productivity growth. Public management involves handling these dilemmas so as to (somehow) steer a course between them that maximises public value.

Recent developments

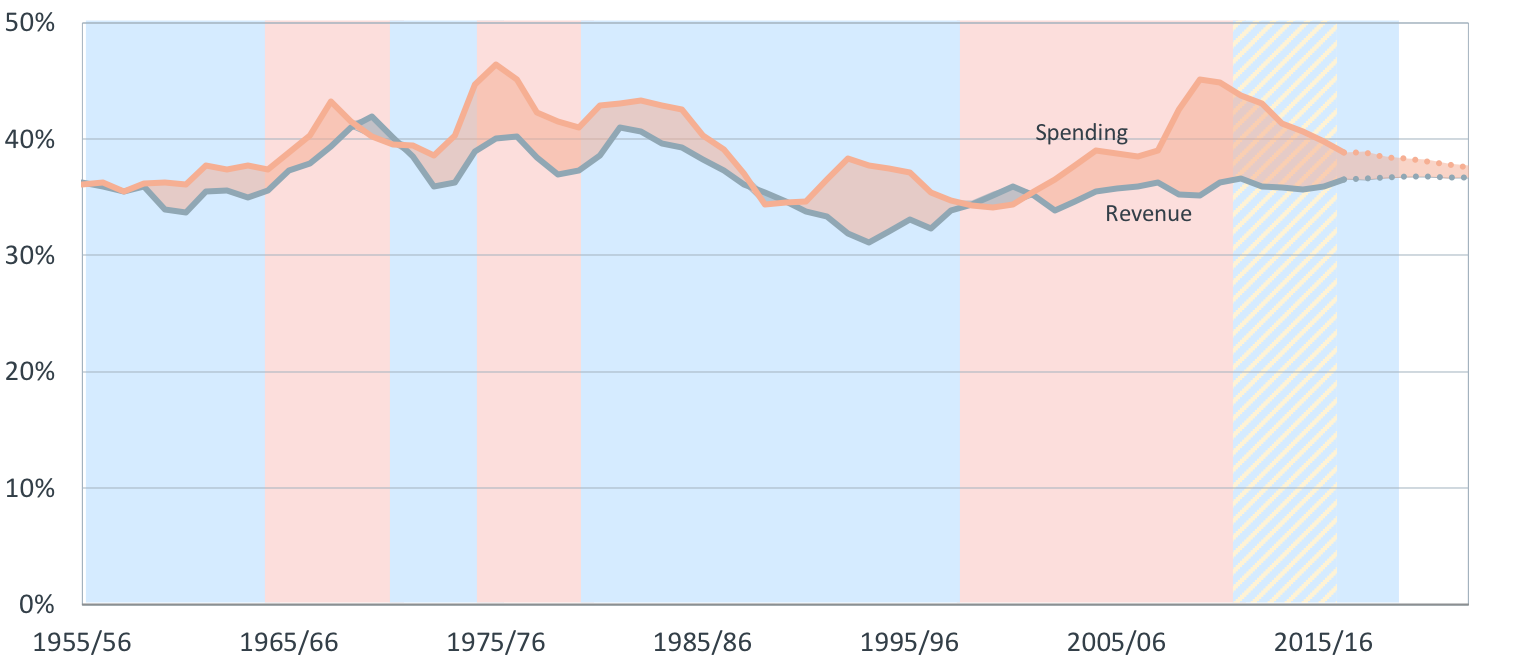

The recent history of public services has been dominated by the austerity programme of the 2010–15 Conservative–Liberal Democrat government, which sought to restore a balance between public spending and government revenues, primarily by cutting back welfare payments and the running costs of public services. Figure 1 shows that their plan sought a rarely achieved balance of current spending and receipts, initially by 2020 but now postponed past 2023. Public spending would (in theory) stabilise at around 37% of GDP – pretty much above the level it has been since the late 1980s.

Figure 1: Tax receipts, public spending and UK deficits as a proportion of gross domestic product from 1995 to 2016, and projected to 2023

Source: Institute for Government, Whitehall Monitor 2018, Figure 3.3.

Notes: A dark pink gap between the spending and revenue lines shows a public sector deficit, and a grey gap shows a (rare) surplus. The government in power is shown by the background shading: pale pink Labour; blue Conservative; hashed Conservative–Liberal Democrat coalition. Dotted lines are projections under autumn 2017 government plans.

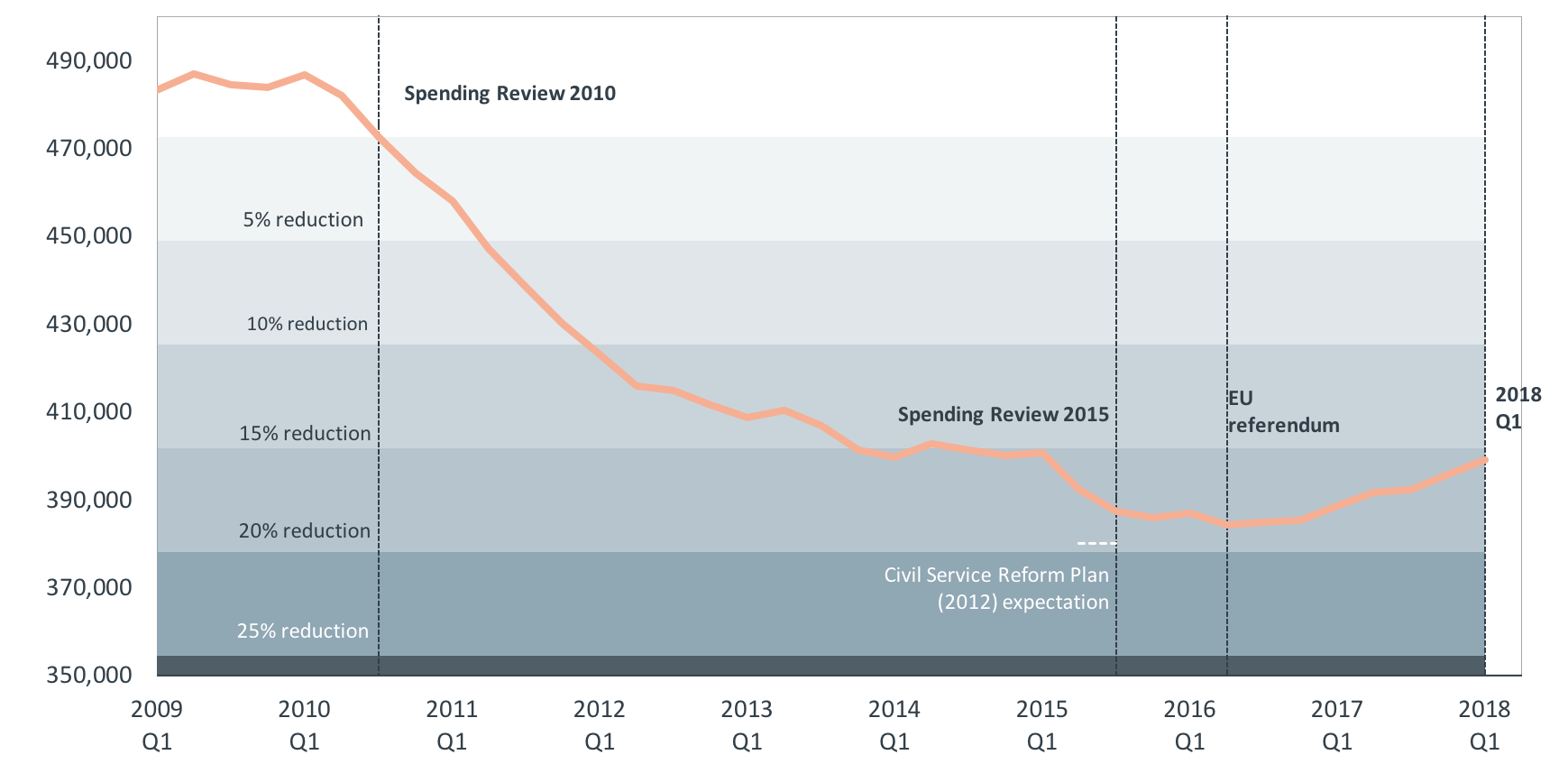

The NHS was exempted from austerity with spending maintained in real terms, but the higher costs of health inflation were not covered. Most spending cuts focused on welfare benefits, policing, prisons, and devolved and local government services, with the civil service exporting many cutbacks to other agencies to accomplish. Nonetheless Whitehall running costs were also targeted and Figure 2 shows that for a year in 2016 the number of civil servants fell below 385,000 – its lowest level since 1940 (when the UK’s population was also far smaller). By 2017, though, this total was rising again as Whitehall geared up for the 500-plus projects involved in leaving the European Union.

Figure 2: The size of the UK civil service, 2009 to first quarter of 2018

Source: Institute for Government, Whitehall Monitor 2018, Figure S7, and updated for Q1 2018.

Much of the apparent fall in Figure 2 may also be rather deceptive, because of the growth of a para-state of contractors (and a few NGOs). These organisations now carry out many functions previously done by Whitehall but do not count in the personnel numbers. In 2017 the UK government as a whole spent as much on contracting with firms for goods and services as it did on paying public sector salaries. There are no grounds for believing that this has in any way saved money, and it also carries large risks because just a few oligopolistic firms dominate public services work. In January 2018 one of these contractors, Carillion with 65,000 employees, went bankrupt, imposing costs of up to £148m on UK government in finding and paying alternative providers to take over their work at short notice. Other firms, including Capita, were on a watch list for similar problems in mid-2018.

In its 2017 general election campaign, Labour called for an end to austerity and ending the multi-year public sector pay quasi-freeze (with rises limited to 1% for all public sector workers, cutting their real pay by around 2% a year). This theme apparently chimed with the public, especially when three terrorist attacks occurred near or during the campaign, drawing attention to reductions of 20,000 in police numbers. Shortly afterwards the Grenfell Tower fire catastrophe dramatised the radical erosion of building and fire safety regulation (see below). Contrary to David Cameron’s sanguine 2014 assessment that spending cuts had done little damage, voters clearly felt that NHS waiting list backlogs, an epidemic of badly potholed roads, ‘banana republic’ safety regulations, and disappearing police and fire personnel mattered a lot. Tory MPs returned from the 2017 campaign to press ministers to end the pay freeze for government sector workers.

Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities, Threats (SWOT) analysis

| Current strengths | Current weaknesses |

|---|---|

| The UK civil service model has a long tradition of being very politically controllable and accountable. Its culture is generalist and non-partisan, able to work with governments of different partisanship and to tackle new issues with some competence. Departmental viewpoints are strongly held in Whitehall, but less so than in many other liberal democratic countries thanks to cross-departmental movements of personnel over their careers. | The lessened but still-dominant ascendency of the generalist ‘policy profession’ within Whitehall feeds into and encourages an ‘amateurish’ pattern of policy-making. It overvalues short-run administrative and organisational changes as keys for increasing public policy effectiveness. This undervalues the importance of long-run and substantive changes, which rely on managers having greater professional expertise specific to each policy area (and requiring more advanced higher education than most UK policy profession staff actually have). |

| Officials are individually and collectively responsive to public opinion, keen to avoid criticisms, and committed to equal treatment of citizens at the point of service. These qualities are (generally) replicated in other public services. | There is no statutory protection of civil servant independence. The ‘Armstrong Doctrine’ holds that ‘the civil service has no constitutional personality separate from that of the government of the day’. So, UK senior civil servants have only a weak capacity to ‘speak truth to power’. They especially have not been able to curtail ministerial hyper-activism (for example, changes made solely for the sake of demonstrating a new minister’s control), pointless party political policy churn, and legislation that was little used after its passage into law. |

| Public administration in the UK is generally effective and reasonably modern. The civil service has a well-developed pattern of continuously or regularly undertaking reforms and looking for best practices elsewhere to adopt. The UK’s record in digitally transforming public services is a reasonable if not outstanding one, especially in the heyday of the Government Digital Service (2011–15), but less so now (see below). | The NPM organisational culture means that senior UK civil service officials may be party-politically neutral, but show a chronic bias towards ‘new public management’ (NPM) approaches. NPM greatly over-values the importance of ‘managerialism’, ‘leaderism’ (exaggerated faith in strong leadership) and public/private ownership for substantive service development. It greatly under-values the salience of digital change, evidence-based policy-making, workforce expertise commitment, and the incremental improvement of services in continuously growing productivity. |

| Whitehall has a strong tradition of contingency planning and rallying around in resilient ways in crises, plus an ability to see issues through despite resources being scarce. | The same over-orientation towards managerial reorganisations and strong leadership has been spread strongly into policing, local government and the NHS by Whitehall interventions. |

| Corruption and fraud in the civil service is rare and through central government vigilance this norm has been extended into devolved governments and other sub-national agencies. | The ‘revolving door’ denotes a set-up where senior mandarins can retire or leave their posts, but then move into private consultancy jobs or posts in public service contractor firms. Critics argue that it also creates a pro-outsourcing NPM bias. Rules supposedly safeguarding the public interest by limiting moves to beneficial jobs are only weakly enforced, as a 2017 NAO report noted. |

| The increased financial involvement of private sector firms in delivering critical public services (via privatisation, the private finance initiative and public-private partnerships) has sometimes worked. But at other times it has weakened the stability of public service, importing new sources of financial instability and risk (as with the Carillion bankruptcy, see above) and poor productivity change (see below). | |

| There have been some notable and recurrent lapses in the equal treatment of some black and ethnic minority citizens, women and people with physical or mental disabilities within the police, prisons service, NHS and local government, with a succession of adverse scandals. The Windrush saga exposed a systematic race-biased Whitehall policy stance enforced over many years (see below). | |

| Citizen redress processes have always been weak in conventional public services (see below). They have been made far more complex and often impenetrable by the contracting and commissioning by private sector firms in services areas, and by NGOs in many welfare state and social services. Legal and administrative provision for complaints and redress in these areas lags many years behind organisational best practice. | |

| A few corruption blackspots remain, especially in areas like overseas sales of defence equipment, and private contractors taking over government-run services on a payment-by-results basis. |

| Future opportunities | Future threats |

|---|---|

| The Brexit move to ‘take back control’ (and its many associated difficulties) may create an ‘overload’ at the centre that impels both ministers and Whitehall and the civil service to cease blocking the delegation of more powers and freedoms to devolved and local governments. | The burden of new legislation and statutory instruments imposed by any abrupt Brexit transition could overload Whitehall capacities, but might be handled better given an extended transition period. An early Deloitte consultants’ report argued that Whitehall really needed 30,000 more civil servants to process over 500 Brexit-related projects, sparking angry denunciations by the May government. Nothing like this level of extra resource has so far been made available. Even though post-Brexit regulatory changes will now be ‘sifted’ by MPs, the planned extensive use of ‘Henry VIII’ powers in the Brexit transition to make new executive orders with reduced parliamentary or public scrutiny means some Whitehall powers may go unchecked. |

| The growing use of social media (aided by the pervasive use of mobile phone cameras to generate photo and video images) has greatly increased the specificity and rapidity of citizen vigilance. The potential ‘audience reach’ of criticisms, and the speed and salience of news of mistakes, have also increased. Officials now confront a stronger discipline of public criticisms. So perhaps responsiveness – in better explaining policies, and in quickly correcting mistakes or services lapses – may improve. | The UK civil service will need to rebuild key skill sets and forms of expertise (for example, in trade negotiations or strategic economic regulation), which have been wound down during the 43 years of EU membership. These cannot be easily or quickly put in place, and will be costly to recreate. Some critics also argue that during the Brexit referendum and the prolonged negotiations in 2016–19 Brexiteers amongst ministers and MPs repeatedly undermined the legitimacy of civil service advice, alleging a pro-Remain bias amongst senior officials whenever policy papers presented information that they found unpalatable. |

| As austerity eases off, some of the pressure for digital changes has also ebbed away, with the Government Digital Service (GDS) budget cut back and an absence of any clear ministerial lead (see below). May has moved digital change out of the Cabinet Office to an expanded Department for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport (DCMS), a ministry with a poor history in this area and little clout with other departments. | |

| A loss of EU migration is likely to adversely impact labour shortages, most particularly in the NHS. | |

| ‘New public management’ strategies plus many years of austerity policies have worn thin the UK state’s capacity to cope with crises and unexpected contingencies. The August 2011 riots in London and some other cities showed one kind of vulnerability, eventually requiring 16,000 police on the streets to bring them to an end. And the 2017 Grenfell Tower disaster and scandals around building safety de-regulation demonstrated another facet of the same underlying fragility (see below). |

New public management, austerity and ‘zombie NPM’

Critics of conservative, state-shrinking policies often characterise them as ‘neo-liberal’, and see uncaring senior officials as complicit in over-cutting government provision. In fact public servants in the UK from the 1980s to around 2005 bought into a rather different set of doctrines called ‘new public management’ or NPM. Its central themes were:

- Disaggregation (chunking up large bureaucratic hierarchies into smaller organisations) to improve responsiveness;

- Competition (especially between in-house providers and private contractors) to improve efficiency; and

- Incentivisation (paying officials and contractors by results) to improve motivations for hitting targets.

NPM continued under the Blair/Brown governments – but in more ‘humanised’ ways, and with concessions to trade union interests.

Many commentators confidently predicted that the coalition government in 2010 would return NPM ideas to centre stage, not least because they had been the orthodoxy when Tory ministers had last been in power (back in 1996–97). But in fact, only one or two NPM-style changes were made – below the Whitehall level. They were implemented in a ‘zombie NPM’ style that soon ran into opposition, causing the intended changes to be heavily modified. ‘Free schools’, for instance, were supposed to boost competition and expand choice, but soon ran into regulatory problems, limiting their spread. The Cameron government also made some play with the idea of backing a ‘Big Society’ in 2010–13 (supposedly preferable to a ‘big state’, and thus providing some ideological cover for austerity). This concept was always tenuous, especially as NGOs and the third sector were among the first to suffer from cutbacks. It disappeared for good after a Commons select committee found little substance to it.

The chief zombie-NPM ‘reform’ was a reorganisation of NHS administrative structures pushed through by Cameron’s first Health Secretary, Andrew Lansley. Eventually implemented in 2012–13, at a huge cost (between £2.5bn and £4bn), it created Care Commissioning Groups, supposedly run by consortia of GPs. CCGs ‘buy’ services from NHS acute hospitals, which were also mandated to ‘commission’ more services so as to allow more private firms to bid for ‘work packages’. The result was a massively complex ‘quasi-market’ scheme that Cameron had to ‘pause’ and try to simplify, before it was finally put into action. Of the promised CCG improvements in commissioning and savings in management costs there has been little or no sign, and instead acute controversies have grown over a ‘postcode lottery’ in access to costly drugs or fertility treatments. Some prominent private sector contracts for acute hospital services have also already failed.

In spring 2018 May and the then Health Secretary (Jeremy Hunt) criticised the Cameron-era changes, admitting that they were dysfunctional. The Prime Minister commented:

‘I believe that, as our NHS evolves, and delivers more joined-up care across different services, we should make sure the regulatory framework keeps in step and does not become a barrier to progress… So I think it is a problem that a typical NHS Clinical Commissioning Group negotiates and monitors over 200 different legal contracts with other, different, parts of the NHS. It is too bureaucratic, inhibits joined-up care, and takes money and people away from the front line.’

May promised new legislation to streamline the system, but the chances of this are currently hard to assess.

Meanwhile in Whitehall austerity meant reversing many earlier NPM changes. The high salaries for leaders under ‘incentivisation’ schemes proved unaffordable, as did the luxury of multiple executive agencies created in the 1990s. Top pay was promptly capped to the level of the Prime Minister’s salary, and many agencies re-absorbed into central department groups. ‘Light touch’ regulation supposed to encourage competition collapsed in financial markets in 2008–10, prompting a huge prudential re-regulation by 2015. The Grenfell Tower disaster in June 2017 showed that building controls and fire safety had been deregulated into meaninglessness (see below).

Detailed analysis of new public management’s claims to have saved money and improved government efficiency also suggested that the whole NPM experiment did not realise any cost reductions or efficiency improvements. And while the structural costs of austerity were diffused, by 2017 evidence accumulated that their consequences had become potentially far-reaching. For example, the annual growth in UK life expectancy, which had been strong before 2010, slowed to a complete standstill after 2011, for no clear reason except the increased stress placed on the NHS.

Digital era governance in the UK

Although ministers still publicly adhered to NPM discourses, the demands of severe austerity proved to be key in some parts of Whitehall finally adopting a completely different public management strategy under Cameron, called ‘digital era governance’ (DEG). As its name implies, DEG strategies focused on the reform potential arising from embracing a wholesale transition to online and digital services. Two other elements directly reversed NPM by stressing the ‘reintegration’ of services, to provide more simplified and cost-effective structures, and ‘needs-based holism’ to ensure that public services meet citizens’ needs in the round (and are not provided in an uncoordinated way to ‘customers’ of highly siloed agencies).

DEG strategies were often poorly implemented by officials trained only in NPM approaches, but austerity pressures were so severe that they prevailed. In 2011 the Cabinet Office required departments to adopt ‘digital by default’ approaches, where at least 80% of services are delivered to people online. The Department for Work and Pensions was catapulted from ignoring online services completely (as it did from 1999–2010) into embracing digital by default as an integral part of the Universal Credit change, a huge benefits and tax credit re-integration push forced through by the Secretary of State for Work and Pensions (and former Tory leader) Iain Duncan Smith.

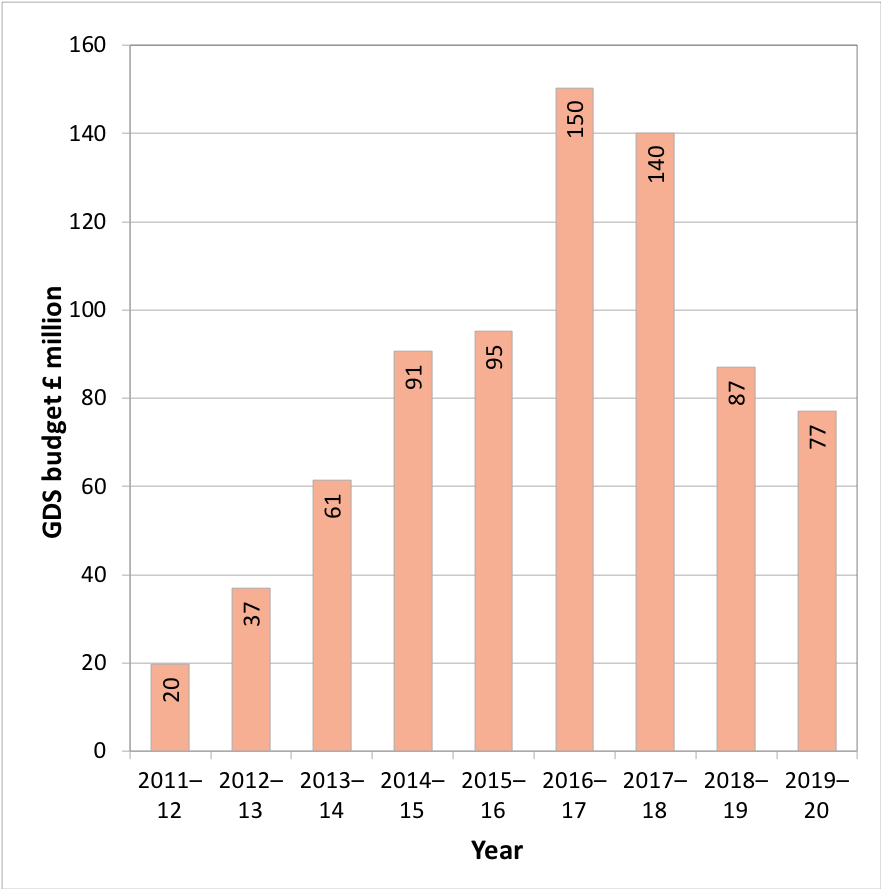

With the backing of Cabinet Office Minister Francis Maude and the Prime Minister, a Government Digital Service was established in 2011 and assigned increasing amounts of funding to develop a single main government website (gov.uk) and put in place online services. Figure 3 shows that its funding expanded greatly, as savings from doing things online were realised, peaking in 2018. However, the ever-zealous Treasury, plus a backlash from departments bringing their IT operations back in-house, curbed its operations from 2016. Funding has now declined appreciably.

Figure 3: The budget for the Government Digital Service, 2011–2020

Source: National Audit Office, 2017

Intelligent centre and devolved delivery

One major problem for the UK’s centralised welfare state is that of establishing a so-called ‘intelligent centre/devolved delivery’ structure, where the digitally scalable services are handled once by Whitehall or national agencies, and local services focus on things that really require in-person delivery. For instance, England has 150 different library authorities, buying books together in around 70 consortia, and each developing their own very limited and very late ebook service. Yet 85% of the book stock is the same across local libraries, and many libraries are being closed by councils under intense austerity pressures. By contrast, there would be huge scaling savings from buying books and ebooks once at national level (which DCMS in Whitehall has never dreamed of doing), and with local libraries just focusing on liaison with local readers and users, plus their community activities and services.

Public service delivery disasters

We noted (in our Audit of the core executive) that the UK polity has a big problem with recurring policy fiascos, mistakes made at the top levels of government and the core executive. But the public administration system has a different if partly similar phenomenon, called ‘service delivery disasters’ (SDDs). These are not due directly to misguided decisions from the top (although these usually play some role). Rather, SDDs are unintended implementation catastrophes arising through the complex choices and interactions of overloaded or misguided ‘street-level’ bureaucrats.

A critically important recent SDD example, whose huge implications for public management are still unfolding at a major public inquiry, is the shocking Grenfell fire disaster in June 2017. Here 72 people were burnt to death and hundreds more injured in a high-rise tower block in Kensington by a fast-moving fire. The blaze spread rapidly through the flammable cladding materials with which the block had been clad in a recent renovation. In the aftermath of the catastrophe it emerged that the building regulations system in England had been rendered completely ineffective by years of de-regulatory activity. Multiple changes had cut back fire service and later local authority involvement in regulation, in favour of making landlords responsible for ‘self-certifying’ safety. At the behest of aggressive building supply contractors, regulations on permissible materials had also been watered down into complete meaninglessness, with a host of radically new cladding technologies introduced for high-rise buildings with no effective checks of their flammability. The end result, clear by summer 2018, was that hundreds of high-rise buildings owned by local authorities were at risk of the same fate as Grenfell.

In addition to dozens of cumulative mistakes that had already created a bad situation, the SDD in the Grenfell case was magnified by many other failures. The responsible Whitehall department (DCLG) had been warned many times by coroners and MPs that fire safety needed new regulations, but did nothing, most notably after a 2009 fire that killed six people and showed the problem acutely. No fire sprinkler systems were fitted in any of around 500 social-housing tower blocks with a single staircase. When Kensington council renovated Grenfell Tower three years before the fire, they failed to spend £200,000 on sprinklers that might have kept its 300 families safe, and went with a lowest-price contract from a marginal contractor and using the very cheapest possible (and as it turns out highly inflammable) materials. The poor workmanship and faulty designs that made the fire worse were not spotted by local building regulations staff. Finally, to compound all these problems, the fire service teams who attended the fire spent their first two-and-three-quarter hours there mistakenly advising residents to stay in their flats (the previous safety advice from smaller fires to avoid smoke), rather than to flee. Some residents were reached and evacuated, but of those who heeded official advice, most were unreachable and died where they stayed.

Other serious service delivery disasters have included the deaths of 90+ patients in a hospital infection outbreak at a Tunbridge Wells hospital placed under extreme NPM managers, and the unnecessary deaths of perhaps 400 patients at Mid-Staffordshire NHS Hospital Trust over a long period of years, where managers coerced staff into losing all respect or care for many people. The squeezing of childcare services has produced a long sequence of cases where children at risk from their parents were neglected by multiple agencies, or not protected from abuse in children’s homes. Similarly, mistakes by the police and probation services in not following up information to prevent harm to vulnerable people, or in releasing dangerous people from custody, created public alarm. And in mid-2017 the government decisively retreated from its earlier NPM commitment to using private sector prisons, as treatment and cost issues emerged.

The squeezing of social care costs under austerity has produced very rapid declines of standards in social care homes, which has led to multiple abuse cases and ever-gloomier assessments by the Care Quality Commission battling to re-regulate the sector. Together with poor care for the elderly in NHS settings, this area became a huge issue in the 2017 election campaign when the Tory manifesto tried to raise more receipts from dementia sufferers’ estates. By mid-2017 social care was rated the most important issue in UK politics by 14% of opinion poll respondents.

A final, purely Whitehall scandal emerged in 2018 over the denial of UK citizenship to dozens of elderly black citizens who had arrived in the UK during the 1950s and early 60s (the so-called ‘Windrush generation’, after an early ship many travelled to the UK on) and been resident here ever since. In 2010 Theresa May became Home Secretary and began cracking down on immigration in an attempt (never remotely successful) to approximate the Tory pledge to reduce net immigration to ‘ten of thousands’ of people. As this policy increasingly seemed fruitless, in 2013 May enforced a ‘hostile climate’ for migrants. Immigration officials who had contact with Windrush generation people began demanding documentation which had never been supplied to them at the time, and refusing to accept evidence of long residence. By 2018 numbers of elderly black people had actually been deported back to Caribbean islands, before it emerged that official documentation of their arrival had existed in the Home Office (in the form of ‘landing cards’) but been lost during reorganisations in intervening years. Cross-partisan pressure from MPs forced the abandonment of the ‘hostile climate’ for Windrush people and their children.

Weak citizen redress

A prominent casualty of the austerity period has been the once-strong mechanisms in British government providing for citizen complaints and redress. A shift to regulation of private or quasi-market provision, and the fact that more and more services have come to be delivered by private firms or NGOs on behalf of public agencies, has made seeking redress far more complex than before. NHS complaints processes have been cut back, despite the escalating level of NHS liabilities for medical mistakes, and the development of ‘no blame’ methods common in other ‘safety bureaucracies’ has proceeded very slowly in healthcare. As delivery worsens, and expenditure cutbacks became more evident, so citizens have become inured to falling ‘service’ standards and to not getting redress for things going wrong. From 2005 on, efforts to get a single public sector ombudsman for England (on the same lines as those in Scotland and Wales) and improve complaints services online were repeatedly stymied by Cabinet Office indifference.

Conclusions

At one time, British public services were a justified source of citizens’ pride in their democracy (famously summed up in the 2012 Olympic opening ceremony’s celebration of the NHS). By 2017, however, the UK’s public services were in a poor condition. Overstretched, staffed by now underpaid workers, facing apparently indefinite real wage restraint, and with services hollowed out by seven years of austerity, they nonetheless still command a great deal of public respect and huge levels of staff commitment. But after two decades of ‘new public management’ the British state’s administrative apparatus is now a fragile thing, vulnerable to acute failures and ‘public service delivery disasters’, and devoid of many of the ‘strengths in depth’ that once sustained it.

This article is from our forthcoming book, The UK’s Changing Democracy: The 2018 Democratic Audit, published by LSE Press.

Patrick Dunleavy is Professor of Political Science and Public Policy at the LSE and co-Director of Democratic Audit there. He is also Centenary Professor in the Institute for Governance and Policy Analysis (IGPA), University of Canberra.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

[…] the civil service, public services and local government have rapidly increased since 2015. Civil service efficacy has radically declined, the quality of public services has significantly worsened, and […]