Australian politics shows why the de-separation of political and administrative careers matters for democracy

One cornerstone of executive politics in established liberal democracies has long been a system for controlling government corruption and malfeasance that separates out clear roles for the changing elite of elected politicians and their advisers, and the permanent administrators running the civil service. Yet in Australia Keith Dowding and Marija Taflaga find that the growing role of special advisers, plus increased mobility from adviser roles into career public-service pathways, is now an integral factor in the re-emergence of substantial ministerial scandals.

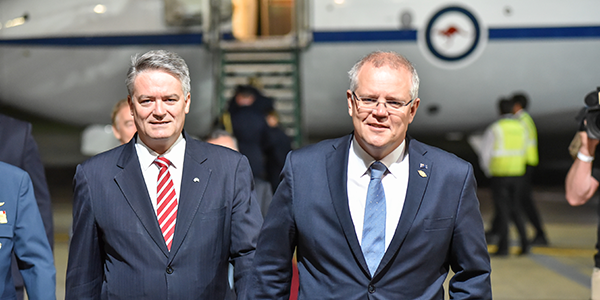

Australian PM Scott Morrison (right) with Minister for Finance, Mathias Cormann. Picture: G20 Argentina / (CC BY 2.0) licence

It is hard to keep up with the number of scandals that are now swirling around federal Prime Minister Scott Morrison’s Liberal-National coalition government in Australia. In the past year, we have had:

- Robo-debt, a crude and ill-advised early effort to use big data from the tax agency in order to cut social security spending;

- grass-gate, where an Energy minister, Angus Taylor, allegedly lobbied the Environment Department to ease development on critically endangered grasslands owned by a relative;

- an allegedly doctored document emerging from Angus Taylor’s ministerial office, used to target a political rival;

- revelations of blatant political bias in grant spending in the $100 million sports-rorts affair;

- and in the Female Facilities and Water Safety Stream among other schemes.

Both the last two items involved government ministers intervening in determining which community organisations received substantial federal grants, so as to direct money into marginal seats and away from safe Labor Party areas just before the 2019 general election.

The government’s reaction to the public’s outrage has been denial and deflection, even shock when Senator Eric Abetz was contradicted by the Auditor General in a Senate inquiry. At the heart of these scandals – these failures of public policy – lies the relationship between ministers in the executive, their political offices and the bureaucracy.

This nexus is neatly demonstrated by the commissioning of the Gaetjens report into how the former Minster for Sport, Senator Bridget McKenzie, handled the ‘sports-rorts’ grants scheme leading up to the 2019 federal election. As Secretary of the Department of Prime Minister and Cabinet, Philip Gaetjens is Australia’s chief public servant. He used to be Secretary of the Treasury (i.e. its administrative head), a job he transitioned to after working as Scott Morrison’s Chief of Staff, a political role. Indeed, Gaetjens has had a celebrated career, moving between the public sector and the political offices of both Morrison and former Liberal Party Treasurer Peter Costello.

In light of Gaetjens’ past working in partisan offices, and the delicate political context facing embattled minister Bridget McKenzie, the validity of the whole process was questioned, then critiqued. The air of political expediency surrounding the report was compounded by the decision to keep it secret because it was advice to cabinet, a claim undermined by revelations that few cabinet members had even seen the report. Whilst not unique, the whole affair highlights the expediency of politics over process and of political management over public integrity. This risks becoming ‘business as usual’.

Changing career structures for political elites

Political scientists have long discussed the rise of the ‘professional politician’ with the growth of industries surrounding politics, including political staff, lobbyists and think tanks. We know political elites are getting younger and are more likely to have worked as a political adviser, increasingly in the ministerial wing rather than the electorate, before entering politics.

Public administration scholars note the growing ‘politicisation of the public service’. Changes across Westminster systems make it easier for politicians to appoint senior bureaucrats, making them more responsive to the political needs of ministers than to the institutional, para-political needs of the department. This was a reaction to the power of mandarins like those portrayed by Sir Humphrey from Yes, Minister. But has the balance swung too far in the other direction?

We call this phenomena career de-separation

Recently in Political Quarterly, we argued that where there was once two separate career paths for policy-makers, one for public servants and one for politicians, increasingly these pathways have become blurred. While politicisation of the public service and professionalisation of politics are both studied, not enough focus has been given to considering their dual role.

Westminster systems evolved to provide professional and clear policy formation. Ministers would set aims and professional public servants would advise them about the best way to achieve them. Politicians came from many walks of life and brought experience from different fields. They might be less conservative than public servants when it came to policy. They entered politics for a reason – to make a difference. Committed to left or right ideas, they hoped, if not to transform society, at least to change it for the better.

By contrast, public servants were people working long-term in the public service, appointed through a competitive process and promoted on merit: they knew they were there for the long-term. They would still be around years after policies were implemented and they would have to deal with problems that might emerge. Senior advisers, in their 50s or older, and having served 30 years, can bring their experience to highlight potential problems and pitfalls in policy initiatives.

These two career paths would play off against each other and, at times, each would find the other frustrating. ‘The civil service are too cautious’, railed the radical politicians; ‘the politicians do not understand the dangers inherent in this policy’, complained the civil servants. One side or the other might prevail, though ultimately decisive politicians could always win, if they were sure that they could ignore the cautious advice.

Consequences of de-separation

That way of doing things has now changed. There is growing evidence that we now have one set of political elites whose careers are intermingled. The career public service has become more politicised as politicians override the merit system and bring people from outside the service. While not necessarily all bad, since such moves can bring useful experience into policy-making, it has altered the nature of career competition within the civil service and weakened promotion on merit there.

The rise of policy advisers or staffers to help ministers devise policy and keep on top of their brief takes policy advice away from professional public servants. Outside of competitive processes, staffers are essentially appointed by ministers. Politically appointed staff are recruited via electorate offices, party central office, policy institutes or from the private circle of the minster, sometimes straight from university. Often young, their average age is mid-30s, a good generation younger than the top public servants. They are unlikely to be around to see the consequences of the legislation they help produce. They will be off to some other policy job, or to parliament themselves. Their ideal path is to ministry.

This article gives the views of the authors, and not the position of Democratic Audit. It first appeared on the PopPoliticsAus blog, and is reproduced here in a slightly extended form. It draws on the article: Dowding, Keith, and Marija Taflaga. ‘Career De-Separation in Westminster Democracies‘, Political Quarterly 91, no. 1 (2020).

About the authors

Keith Dowding is Distinguished Professor of Politics and Philosophy at the Australian National University. His most recent books are: Economic Perspectives on Government, co-authored with Brad Taylor, Palgrave Macmillan, 2019; Rational Choice and Political Power, Bristol University Press, 2019; Power, Luck and Freedom: Collected Essays, Manchester University Press, 2017; and Policy Agendas in Australia, co-authored with Aaron Martin, Palgrave, 2017.

Marija Taflaga is a Lecturer at the School of Politics and International Relations at the Australian National University . Her most recent publication is: ‘Who Does What Work in a Ministerial Office: Politically Appointed Staff and the Descriptive Representation of Women in Australian Political Offices, 1979–2010‘, co-authored with Matthew Kerby, Political Studies, June, 2019.

.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.