Economic voting and party positions: when and how wealth matters for the vote

Does the ownership of economic assets matter for how people vote? Drawing on new research, Timothy Hellwig and Ian McAllister find the answer is yes. They argue that by changing their policy positions, parties can shape the influence of asset ownership on voter decisions, if there is sufficient party polarisation.

Picture: Pixabay/Public Domain

The politics of asset ownership have received much attention in the aftermath of the Great Recession as researchers and financial advisers alike weigh the value of how best to store and build personal wealth. But the push for ownership is far from new. One of Margaret Thatcher’s many ideas was to create a ‘property-owning democracy’. This belief in the virtues of private ownership aligned well with the Tories’ belief in citizens controlling their own wealth in the marketplace rather than surviving on state welfare.

In the ensuing decades, policies designed to foster homeownership have spread to other advanced capitalist democracies, notably in the US, with George W. Bush’s call for an ownership society in the 2000s, and to middle-income economies in places like Latin America as well. Over time, the policies to foster ownership have evolved into preferential tax policies to encourage participation in equity markets.

How has this advancement of asset ownership influenced electoral politics? Political scientists have examined whether wealth – conceived in terms of home or business ownership, savings, and holdings of shares of stock – matters for how voters decide. A growing body of research concludes, perhaps not surprisingly, that owners vote for centre-right parties such as the Conservatives in Britain, Republicans in the United States and the Liberals in Australia. Once in power, centre-right parties are most likely to advance policies aligned with the interests of the owners to prevent their wealth being expropriated through taxation. In contrast, centre-left parties strive to curry favour among those individuals whose chief asset is their own labour. This ‘patrimonial’ logic of electoral politics harkens back to Marx in assuming that elections serve to play out the class struggle.

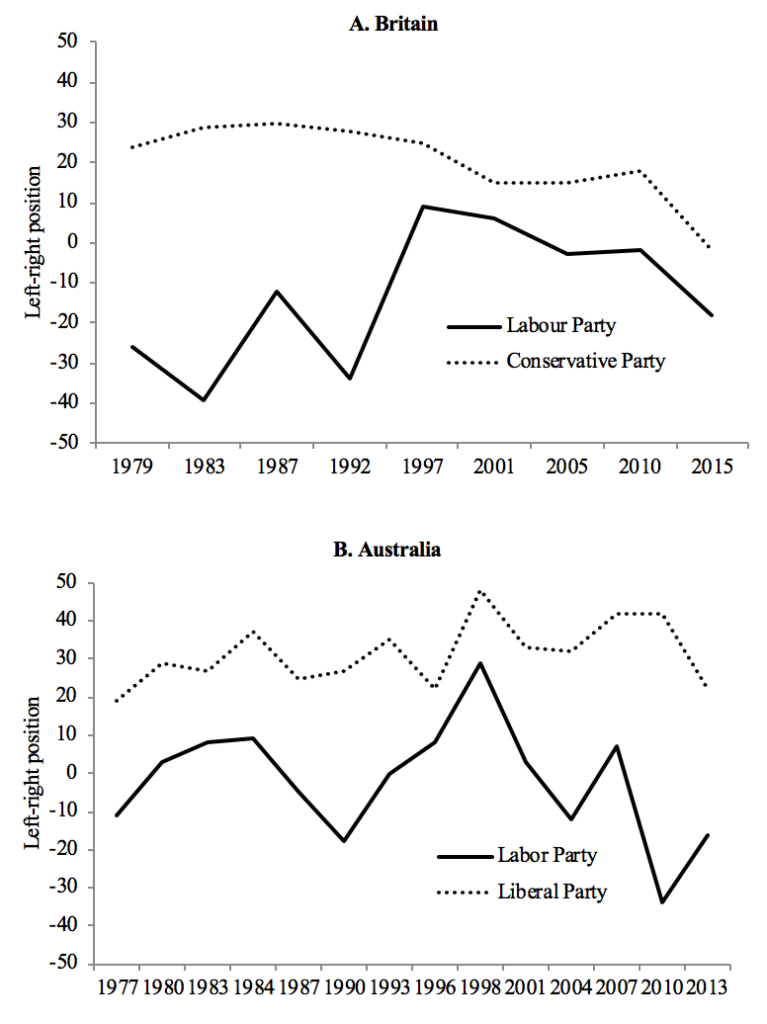

This story, however, leaves out the role of the electorally motivated political party. It assumes that parties on the right uniformly favour cutting taxes and those on the left always advocate pro-spending policies. Of course, this is not the case, and we have to look no further than Britain as case in point. Labour in the 1990s and 2000s was demonstrably less favourable to spending than it was previously and has been since. And, with fits and starts, the Tories have moderated their market-based economic policy. Figure 1 shows this graphically, in terms of the two parties’ election manifestos. Higher values on the vertical axis depict more rightward-leaning policy positions and lower values views more to the left.

Figure 1: Left-right positions of major parties, Britain and Australia

Source: Comparative Manifesto Project.

In our research, we argue that this jockeying of positions over time matters for whether voters decide to draw on their identities as asset owners when selecting parties to represent their interests. When the parties provide a choice, as was the case in Britain during the 1980s, then ownership ought to exert an influence, with owners of housing and shares supporting the Conservatives. But when the leftist alternative moderates, as Labour did after the 1992 election, the choice is less clear and the ‘patrimonial voting’ story less plausible.

To assess our claim, we examine post-election survey data which provides information on the parties’ policy positions, the respondents’ ownership status, and their vote choice. We first analyse the Australian case, which has been dominated by two parties with clear positions on welfare policy and economic management. Like Britain, the Australian parties have at times converged with respect to these positions, as Figure 1 indicates. Unlike Britain, however, we are fortunate to have information on the ownership status of survey respondents over six elections (from 2001 to 2016 from the Australian Election Study).

We find that when the Liberal and Labor parties are seen by voters as holding similar positions, patrimony has no effect on voter choice. It is only when voters consider the parties’ policies to differ that the traditional patrimony argument finds support. We further show that this effect of policy distance is stronger for higher-risk share ownership than for lower-risk home ownership.

Do these findings generalise to electoral democracies more broadly? To date, cross-national research on assets and voter choice has been limited by data availability. We are able to examine recently available data from the Comparative Study of Electoral Systems which includes information on ownership. Employing data from 25 countries, we examine the effect of assets on voting for centre-right parties. In some cases, like Switzerland, the parties were distinct in their economic policy views, while in others, like Japan, they were almost indistinguishable. Results of these analyses echo those from Australia. Ownership increases voter support for the centre-right but only when the parties are sufficiently polarised on economic policy matters. When polarisations are below the 25-country average, then a change in ownership status is no longer a factor contributing to the voter’s decision. Party positions, in short, provide an important scope condition for the presence of patrimonial economic voting.

Our research provides an important corrective to theories of asset ownership and party choice. The electoral benefits to political parties for advancing an ‘ownership society’ agenda, in the mould of Thatcher or Bush, depends on the positions advanced by their opponents. This insight helps us to understand why assets have a greater electoral effect in some countries than in others. Some scholars suggest that differences in welfare state policies may provide an explanation, with ownership playing a more pivotal role in generous welfare states which levy high taxes on their citizens (e.g., Denmark or Sweden) compared to less generous, low tax, nations (like the UK or USA). Our polarisation story suggests an alternative explanation. Ownership-based voting has weakened in recent elections in the US and Britain not because assets matter less to individuals but because the parties have differed little with respect to their positions on the economy.

The post gives the views of its authors, not the position of Democratic Audit. It was first published on LSE’s British Politics and Policy blog . It draws on the authors’ published work in Political Studies.

About the authors

Timothy Hellwig is Professor of Political Science and, for 2017–2020, Remak Professor of European Studies at Indiana University. He is the author of Globalization and Mass Politics: Retaining the Room to Maneuver (2014, Cambridge).

Ian McAllister is Distinguished Professor of Political Science at The Australian National University, Canberra, and is a Director of the Australian Election Study and a former chair of the Comparative Study of Electoral Systems.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.