From the European debt crisis to a culture of closed borders: how issue salience changes the meaning of left and right for perceptions of the German AfD party

Political parties are traditionally described as being on a left-right spectrum according to their economic policies. However, socio-cultural dynamics also contribute to the public perception of parties. Looking at the case of Alternative für Deutschland, Heiko Giebler, Thomas M. Meyer and Markus Wagner show how shifting issue salience from one to the other both by the party and voters affects how the party is perceived in terms of left and right.

Picture: vfutscher/(CC BY-NC 2.0) licence

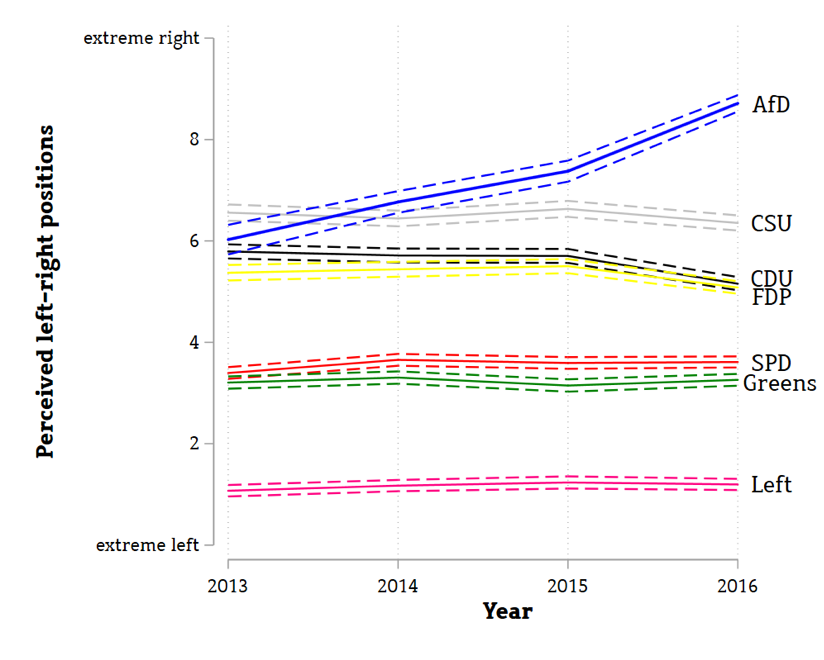

While the ideological perception of some parties remains relatively stable over time, for others it varies considerably. As can be shown using data from the German Longitudinal Election Study (GLES), the Alternative for Germany (AfD) is a good point in case: in 2013, shortly after the foundation of the party, the average perception of the AfD was that of a party slightly right of the centre of the ideological left-right dimension. The AfD’s position did not differ significantly from that of other centre-right parties such as the Christian Social Union of Bavaria (CSU) which was and is part of the government coalition. In the meantime, people’s perceptions have changed considerably. Especially since 2015, the AfD has shifted substantively to the right, as can be seen from Figure 1. In the eyes of the German population, the party now clearly constitutes a radical-right party, tremendously increasing party system polarisation.

Why has the perception of the AfD changed so much? There might be many reasons of course; here, we want to focus on one of them: what people understand as ‘left’ and ‘right’ can be very much context-dependent. More precisely, differences in issue saliency, both for citizens as well as for political parties in their public communication, can change the substantive meaning of the left-right dimension.

Figure 1: Perceived left-right placement of German parties over time

Note: Data is taken from the German Longitudinal Election Study Online Tracking Surveys. Dashed lines indicate 95% confidence intervals for the mean perceived party positions: Alternative für Deutschland (AfD); Christian Social Union of Bavaria (CSU); Christian Democratic Union (CDU); Free Democratic Party (FDP); Social Democratic Party (SPD); Greens; and the Left Party (Die Linke).

The meaning of ‘left’ and ‘right’

In politics, concepts such as ‘left’ and ‘right’ are often used as heuristics. In most established democracies, the vast majority of citizens are able to place parties as well as themselves on this dimension. Using such a heuristic makes it easier for parties, the media and voters alike to reduce the complexity of political conflict and policy positions. Consequently, the left-right dimension serves as an ‘amorphous vessel’ which – during the process of complexity reduction – can be associated with different issues in different situations. ‘Left’ thus means something different in the context of Green parties than in the context of social democratic parties, it meant something different in the 1970s than it does today and a banker’s interpretation might vary from one of a teacher.

We follow the assumption that there are two political conflict dimensions primarily structuring political competition in the European party systems: on the one hand, there is the ‘classical’ economic conflict dimension, on which ‘left’ or ‘left-wing’ parties prefer more state benefits and regulation and ‘right’ or ‘right-wing’ parties demand less public involvement, free markets and low taxes. On the other hand, there is the socio-cultural dimension, on which ‘left’ parties advocate for more individualism, gender equality and cultural diversity, while ‘right’ parties favour authoritarianism, nationalism and traditionalism. Hence, complexity reduction means that these two dimensions of political conflict have to be transformed into only a single left-right dimension.

We argue that how far parties are considered ‘left’ or ‘right’, not only depends on the actual positions they hold on these dimensions, but also on which of those two sub-dimensions they are primarily associated with. To illustrate this point: a party that demands economic redistribution but holds more right-wing socio-cultural positions will be considered left-wing if perceived through the lens of the economic sub-dimension. If the socio-cultural sub-dimension is more salient, however, the party will be perceived as more right-wing. In other words, a party’s left-right position is not the mere average of socio-economic and socio-cultural positions but a weighted average. The weighting factor is the magnitude of association and salience.

The political agenda of the AfD

To some extent, parties are responsible themselves for whether they are associated with economic or socio-cultural topics. They can set a certain issue agenda in their public communication and through this contribute to how voters conceive of party positions. By highlighting certain issues and, for example, putting special emphasis on socio-cultural issues, a party with right-wing socio-cultural and moderate economic positions thus co-determines whether it will be perceived as more or less right-wing. What a party talks about is what it gets associated with.

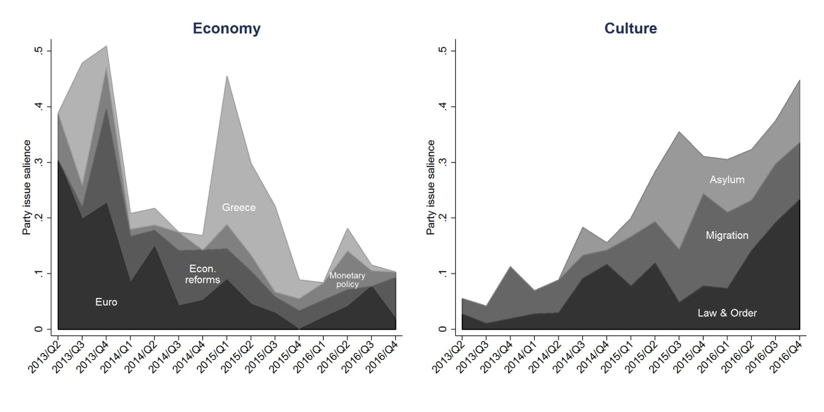

Figure 2: The AfD’s issue salience over time

Note: Figures are based on computer-assisted content analyses of the AfD’s press releases.

The political agenda of the AfD has changed considerably during the past few years, as an analysis of press releases from 2013 to 2016 (Figure 2) shows: while in the founding phase, economic issues were predominant, the thematic emphasis has shifted increasingly to socio-cultural issues such as migration, integration and the role of Islam. Considering that the AfD is perceived as much more right-wing on this dimension than on economic issues, this shift in emphasis can also explain the changed perception of the AfD as a radical-right party.

The importance of voters’ issue emphasis

Another approach to explaining the changed perception of the AfD looks at developments in the public agenda and discourse. Irrespective of parties’ agenda-setting attempts, voters have their own ideas of what issues they consider to be important for themselves or for their country. Such perceptions can change for example by exposure to the specific media content or exchanges in an individual’s personal environment. If socio-cultural issues gain importance, left-right-positions of parties will also be more likely be associated with a party’s socio-cultural position. If the media and personal environment of many citizens changes – as was the case, for example, during the so-called ‘refugee crisis’ in 2015 – then a party will also be associated more strongly with its socio-cultural position. This underlines our argument that perceptions of political competition and party positions are influenced by party behaviour (supply-side) but also by voter characteristics (demand side).

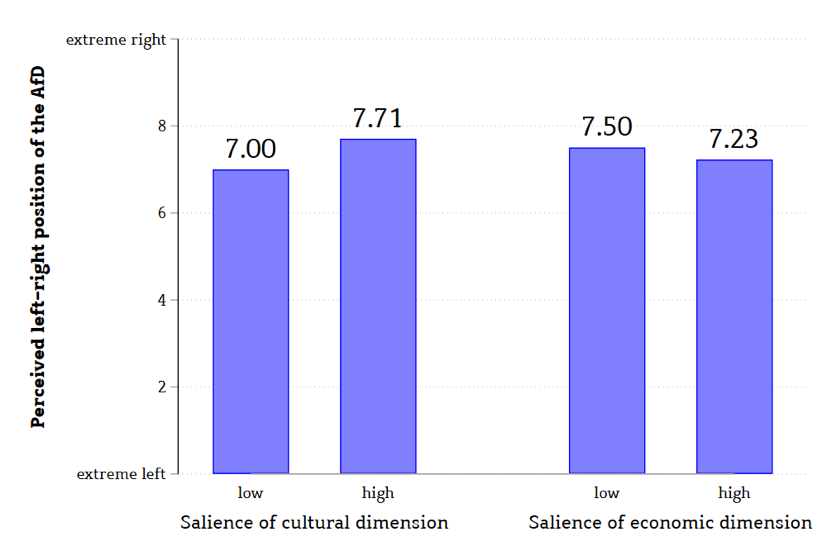

Figure 3: Perceived left-right placement of the AfD depending on individual salience

Note: Data is taken from the German Longitudinal Election Study Online Tracking Surveys.

In principle, this effect should be observable for all parties. Especially for the AfD, however, the (perceived) difference between economic and socio-cultural issues is large enough that it plays an important role even when the thematic agenda shifts. As socio-cultural issues increase in significance in the eyes of the voters – as was the case particularly in 2015 and 2016 – the perception of the AfD on the left-right dimension will be influenced primarily by the right-wing socio-cultural position and hardly by the neither left- nor right-wing economic party position. In a simplified way, this is shown in Figure 3: pooling survey data from 2013 to 2016 – again taken from the GLES – we see how the perceived positions of the AfD shifts to the right if socio-cultural issues are salient for the individual while this is not the case if socio-economic aspects dominate.

Conclusion: the changing meaning of left and right

Two conclusions can be drawn from these results: firstly, the meaning of ‘left’ and ‘right’ varies across voters and parties, but also over time. This is important as it means that, for example, left-wing voters are not automatically well represented by ‘left-wing’ parties; rather, it depends on which topics voters and parties associate with the concepts ‘left’ and ‘right’. Only if the ascribed salience of different topics overlaps, we can be sure that a left-wing voter is represented by a left-wing party. Secondly, parties can influence their (perceived) position as left-wing or right-wing by changing their communication agenda. A stronger focus on a moderate economic policy position can thus for example push radical socio-cultural positions into the background and move a party in the citizens’ perspective more to the centre. Such shifts in agenda-setting are particularly important when parties want to change their perceived position without deserting their principles and positions. Since parties are often scrutinised for position-switching, talking more or less about certain issues might be the preferred option for a party to change its perceived left-right position.

This post represents the views of the authors and not those of Democratic Audit. It is based on the authors’ article ‘The Changing Meaning of Left and Right: Supply- and Demand-side Effects on the Perception of Party Positions’ , published in the Journal of Elections, Public Opinion and Parties, which is available as open access.

About the authors

Heiko Giebler is Research Fellow and Head of the Bridging Project ‘Against Elites, Against Outsiders: Sources of Democracy Critique, Immigration Critique, and Right-Wing Populism’ (DIR) at the WZB Berlin Social Science Center in the Department ‘Democracy & Democratization’. His main research interests are political behavior, electoral campaigns, and populism.

Thomas M. Meyer is Associate Professor of Political Science at the Department of Government, University of Vienna. He works mainly on parties, their messaging, electoral competition and coalition governance.

Markus Wagner is Professor of Political Science at the Department of Government, University of Vienna. His research looks mainly at political parties and electoral behavior, with a particular focus on the role of issues and ideology for how parties compete and how voters decide.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.