Audit 2017: How effectively is the representation of minorities achieved in UK public and political life?

As part of our 2017 Audit of UK democracy, Sonali Campion and Ros Taylor examine the extent to which the representation of minorities in the UK operates to foster or to damage democratic public life. Where previous historical inequalities and discrimination against ethnic minorities are being rectified, is the pace of recent change fast enough? Are there areas where we are moving backwards?

A crowd at the London Mela festival of Asian culture in 2011. Photo: Manoj Vimalassery via a CC-BY-NC-SA 2.0 licence

This article was published as part of our 2017 Audit of UK democracy. We have now published: The UK’s Changing Democracy: The 2018 Democratic Audit with LSE Press, available in all ebook formats. You can download the whole book for free, and individual chapters, including a fully revised version of this article.

What does democracy require in terms of ethnic and religious equality?

● Citizens of all ethnicities and religions must enjoy genuine equality in terms of civil rights. They must be free to practice their beliefs and customs (as long as these do not restrict the rights of others)

● Political and public life should be organised to maximise the equal chances of minorities to be involved in democratic politics – to vote and stand for election, to take part in party and political processes, to contribute to public debate and policy decisions, and to rise to the top in elected public office.

● Employment in the public service sector (and in firms working on public sector contracts) should serve as exemplars of good practice in improving minority representation more broadly.

● No minority group should be subject to differential discrimination in political or public life or by the law, nor to prejudicial discussion in terms of public and media discourses.

● Where barriers to inclusion clearly exist, public regulation or interventions should be undertaken to secure appropriate and feasible ameliorative actions (consistent with maintaining the civil rights of all citizens).

Recent developments

In the 21st century the UK is home to more ethno-religious identities than ever. This diversity has developed over a relatively short period of time, in a significant part due to immigration especially from former UK colonies since World War II, and to some in-migration of EU citizens since 1973. Changing attitudes towards religion have also played a part, for example, resulting in a decline in Christian affiliations.

While increasing multiculturalism and religious variation have the potential to enrich British society, such social changes do present public policy challenges for Western liberal democracies. This is particularly the case in the current geopolitical climate, where conflict in the Middle East and Afghanistan, and the growth of a European migrant crisis and Euroscepticism (to name but a few) are fuelling tensions between communities. Concerns over immigration and social change have clearly contributed to the growing popularity of right-wing populist politicians and there are indications that racist attitudes in the UK are once again on the rise after years in decline.

Political responses to external threats have in many cases done little to alleviate tensions and in some areas have arguably exacerbated them with clumsy counter-radicalisation policies, which focus on tackling extremism rather than addressing disadvantage and promoting integration. For example, the Prevent strategy has been criticised for its ‘stigmatising surveillance of one particular [Muslim] community’, rather than building the educational capacity to discuss contentious issues or deliver effective civic education.

One-dimensional reporting about ethnicity and religion is also feeding into tensions. One example is the Sun headline in November 2015 claiming that “1 in 5 Brit Muslims’ sympathy for jihadis”. The article was based on misrepresented poll data from Survation, who were quick to distance themselves from the unauthorised interpretation of their study. The incident led to both an outcry and mockery on social media and The Sun was eventually forced to admit that its headline was ‘significantly misleading’. Furthermore, not all discriminatory coverage – for example of Romanians and Bulgarians in the run up to the lifting of transnational controls – is called out so effectively.

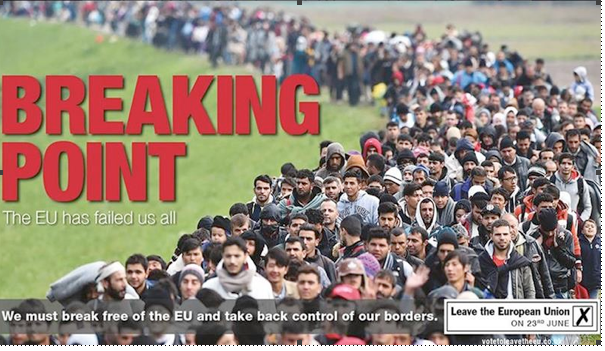

The rise of UKIP as an anti-immigration, Eurosceptic party also seems to have gone hand-in-hand with a revived acceptance of ‘banal racism’ in other areas of the media and public life. During the Brexit campaign Ukip’s ‘Breaking Point’ poster urged voters to “break free of the EU” and depicted a crowd of refugees – and the image was widely circulated on social media. Although Michael Gove, one of the leaders of the Leave campaign, sought to distance himself from this, the damage was clearly done.

Figure 1: The controversial UKIP Brexit referendum poster

In the immediate aftermath of the referendum, both the Muslim Council of Great Britain and the Polish embassy reported outbreaks of racist and xenophobic incidents, including cards reading ‘No more Polish vermin’ pushed through eastern Europeans’ letterboxes. These incidents show a strong anti-immigrant minority view. Such extreme views also seem to receive regular legitimation from tabloid press headlines that repetitively cover immigration issues in an alarmist and stigmatising fashion.

Figure 2: Headlines about immigration in a UK tabloid newspaper

Race-related hate crime rose 37 per cent in England and Wales between 2011/12 and 2015/16, while hate crime based on religion rose 172 per cent in the same period. At the same time, the Equality and Human Rights Commission has noted increasing incidents of hate crimes, with racial, Islamaphobic or anti-Semitic motivations in England. This contrasts with Scotland, where there was a significant drop in charges reported with ‘a religious aggregation’ in 2014-15. (The incidents of religious abuse that did take place there were predominantly aimed at Catholics and Protestants). Police noted a peak in race and religious hate crimes after the murder of soldier Lee Rigby and a rise in hate crime after the Charlie Hebdo terrorist attack in Paris. So policy debates around ethnic inequalities and religion and belief are taking place against a highly charged atmosphere, raising new challenges for the UK’s traditionally low-key ways of handling these issues.

Mainstream politics and ethnic tensions

Even mainstream politicians appeared to be adopting ‘dog-whistle’ strategies to mobilise ethnic and religious divisions for political ends. When Barack Obama reiterated his call for Britain to stay in the EU on a 2016 visit to the UK, prominent Leave campaigners Boris Johnson and Nigel Farage both suggested the President’s ‘part-Kenyan’ roots were to blame for his ‘anti-British’ attitude.

Early on in his failed London mayoral campaign, Zac Goldsmith started using the word ‘radical’ to describe his Pakistani Muslim opponent Sadiq Khan. Goldsmith claimed he was using the word to describe the radical politics of the Labour leader Jeremy Corbyn. But media commentators were quick to pick up on the Islamaphobic undertones, especially when a Daily Mail article by him a week before polling day was illustrated with pictures of London’s 7/7 bombings. Goldsmith was also criticised for targeting London’s Hindu, Tamil and Sikh communities with leaflets making ‘reductive and condescending assumptions’ about their priorities, and seeking to mobilise historic tensions between Pakistanis and Indians. A backlash against an apparent attempt to exploit or exacerbate London’s ethnic divisions for political ends seems to have played a role in Goldsmith’s defeat by Khan, and his later loss of his Richmond seat to the Liberal Democrats in a parliamentary by-election.

Nor has Labour managed to escape rows over religion and ethnicity. In April Naz Shah, MP for Bradford West was suspended for an allegedly anti-Semitic graphic she shared on Facebook in 2014 (before she was elected). Former Mayor and key Corbyn ally Ken Livingstone then tried to defend Shah and was also suspended from the party as his comments were also viewed as anti-Semitic. The incident prompted Jeremy Corbyn to launch an inquiry into racism in the Labour Party, later denounced as a whitewash by most Jewish groups. Its chair, Shami Chakrbarti, was shortly after promoted to the House of Lords and became one Corbyn’s closest shadow cabinet colleagues.

Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities, Threats (SWOT) analysis

| Current strengths | Current weaknesses |

|---|---|

| Politicians in the ‘mainstream’ parties (especially the Conservatives, Labour, Liberal Democrats, Greens, and the SNP and Plaid Cymru) have normally renounced resorting to any ‘dog whistle’ politics that exploits voters’ evident concerns over immigration and the changing social character of some cities for partisan ends. With some prominent exceptions and lapses, political elites held a ‘self-restraint’ line against exploiting social tensions. In London, recent evidence suggests that this position enjoys wide popular support, but this is not the case elsewhere in the country | Populist parties and sections of the right-wing press are increasingly stigmatising sections of the population for political/commercial gain, adding fuel to division and discrimination, and promoting crude stereotypes around minority groups |

| Britain has a reasonable track record of promoting the integration of immigrant communities, particularly when compared to neighbours like France and Belgium | The Leave vote in the Brexit referendum was clearly driven by concerns about immigration both of EU migrants, refugees arriving from Europe’s neighbours and the possibility of Turkish accession to the EU |

| Austria, Germany and France have all witnessed local or national bans on Muslim women’s dress; there have been few such calls in the UK | The rise of UKIP has put the previous elite ‘self-restraint’ ethos on exploiting social tensions under more stress. The stance has become associated with elites’ lack of frankness about globalisation and unwillingness to recognise many voters’ concerns |

| The proportions of ethnic minorities in UK politics, public life and senior business positions are increasing, albeit relatively slowly. However, some communities are significantly better represented than others, e.g. those of Indian origin and descent | Political responses to immigration issues have tended to focus on economic responses, without fully engaging with cultural concerns held by anti-immigration voters |

| Multicultural policies, while they are associated with more peaceful societies, can also make ethnic majorities feel unsafe and discriminated against |

| Future opportunities | Future threats |

|---|---|

| Promoting religious literacy, both at schools and in the workplace, could do much to expand people’s awareness of other faiths | Recent terrorist attacks in Paris and Brussels have prompted a rise in hate crime. Xenophobic violence also surged after the EU referendum |

| The government has announced recent plans to promote English learning among migrants to offer greater support for tackling discrimination and disadvantage among minority communities – and such provision could easily be expanded | The evolution of migration pressures on the EU as a whole, and specifically on the UK (e.g. via the now scrapped Calais ‘jungle’ camp) will assuredly influence UK voters’ attitudes further |

| Evidence from Germany suggests that political intervention early on combined with curbs on the far right may pre-empt xenophobic violence | Uncertainty about the future residency status of EU migrants in Britain continues, with fears they may be used as a ‘bargaining chip’ in Brexit negotiations. The scale and atmosphere of EU migration to the UK (and of UK citizens moving to EU countries also) will be strongly affected by the outcome of Brexit negotiations |

| Liberal values (e.g. gender equality, sexual minorities and free speech) could be better promoted among ethnic and religious minority communities. But this would need to be done not in a way that targets individual communities with stereotyped assumptions about their existing attitudes | The major future risk may be that polarisation increases between majority attitudes and those of specific minorities, especially some sections of the Muslim community, accentuating some existing disadvantages |

| The government has established a Controlling Migration Fund, designed to alleviate pressure on councils, schools and NHS services when a region experiences a large increase in inward migration, and so encourage community cohesion |

We look next at five deeper-lying and continuing major issues relating representation in public life: the representation of minorities in political life; ethnic diversity in the media; the treatment of minorities in the criminal justice system, and the education, and employment and income situations of ethnic minorities.

Representation in political life

Variations in the understanding of ethnicity have impaired understanding in this area. Where data are collected, they tend to focus on “black, Asian and minority ethnic” (BAME) people, i.e. those of non-white descent. This categorisation is of limited usefulness, because it fails to acknowledge the multifaceted nature of the UK’s growing diversity. The umbrella label groups the experiences of very different minority communities into one category. It also fails to acknowledge the challenges faced by some white minorities, such as migrants from eastern Europe. However, due to the limitations of the data and analysis available, we must focus predominantly here on those ethnic minorities included in the BAME category.

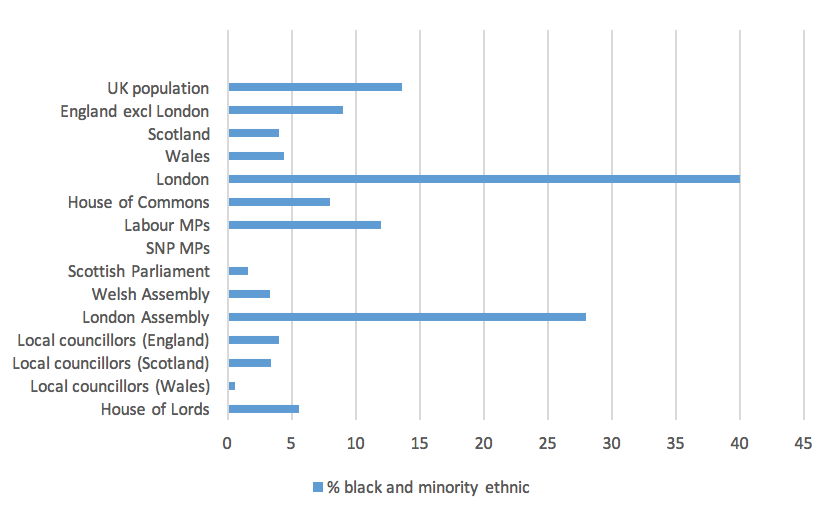

The 2016 Annual Population Report found that 13.6% of the population came from non-white backgrounds. However, minorities remain underrepresented in public life. Although more BAME MPs than ever before (52) were elected in the 2017 general election, the number would have to rise to 88 for the House of Commons to accurately reflect the population as a whole. Sajid Javid MP and Priti Patel MP remain the only non-white Cabinet Ministers. More positively, the percentage of ethnic minority female MPs in the House of Commons increased from 1.5% to 4% between 2010 and 2017 (with a current total of 26).

Chart 1: The percentage of ethnic minorities in various political bodies and populations

Source: House of Commons Library, Greater London Authority, Scotland’s census

Diversity in the media

Ethnic minorities make up 6 per cent of journalists, though that figure conceals major variation between ethnicities, with black journalists accounting for just 0.2 per cent of the workforce. But the problem extends beyond just such numbers. There is a lack of diversity in the kind of stories that are reported. And excluded voices are often only brought in to stories dwelling on extremes or “otherness”. On the flipside, BAME journalist who do break into the industry are frequently expected to comment on ‘minority issues’ or those that relate to their ‘own communities’ while predominantly white male journalists dominate the mainstream. Commentator Nesrine Malik describes how a ‘fundamental misunderstanding‘ of networks can be hermetic and self-perpetuating without being actively racist.

The portrayal of religion and belief in news and current affairs is too often clumsy and lacking in nuance, which has been attributed to a lack of religious literacy among reporters. Studies have noted a foregrounding of stories focusing on the differences between Islam and British/Western culture. References to extreme forms of Islam are 21 times more common than mentions of moderate Muslims. Journalists themselves are far more likely to have no religion (61 per cent) than the population at large (28 per cent).

Treatment in the criminal justice and penal systems

Ethnic minorities continue to be over-represented throughout the criminal justice system. At every stage from being stopped and searched to prison populations, ethno-religious minorities (predominantly those who are black, of mixed parentage, or Muslim) form a majority. Data from the Youth Justice Board indicated that in 2014-15, 40 per cent of prisoners in young offenders’ institutions came from a BAME background. In 2016 Muslims accounted for 14.6 per cent of the prison population, sharply up from 7.7 per cent in 2002.

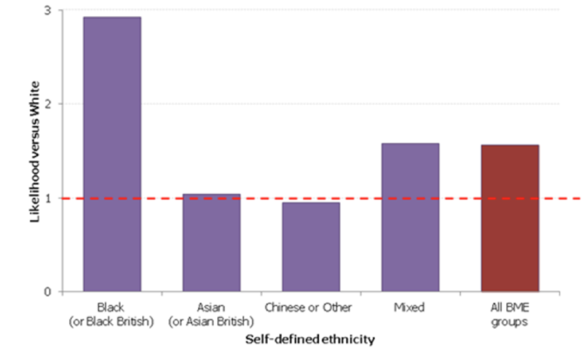

Chart 2: The likelihood of being arrested by people’s self-defined ethnic group, compared with those from white ethnic groups – England & Wales, year ending March 2015.

Note: A score of 1 shows an ethnic group being treated identically with white people; a score above 1 shows a comparatively high arrest rate, and below 1 shows a low arrest rate. Sources: Home Office and Statistics on Race and the Criminal Justice System 2014

In the year to March 2015, BAME people were one and a half times as likely to be arrested as whites. Black people were three times as likely. BAME groups are also more likely to receive longer sentences – the average custodial sentence length for white defendants is 17 months, compared to 25 months for black or mixed people, and 20 months for South Asian defendants.

The disproportionate numbers of BAME minorities in the justice system is not new, but attempts to address it have so far been unsuccessful. The 2014 Young Review, which looked specifically at the experiences of young male black and/or Muslim offenders, found the disadvantage in BAME communities contributed, along with assumptions based on crude stereotyping or outright racism. These factors made it harder to effectively rehabilitate and reduce reoffending rates among these groups. The report also emphasised that the overrepresentation of ethno-religious minorities ‘does not exist in isolation from other unequal outcomes’, both in the criminal justice system and other sectors.

Minority representation in the staffing of the criminal justice sector also remains low, with minimal change over the last five years. Although ethnic minorities are well represented in relation to population within the Ministry of Justice and the Crown Prosecution Service, they are poorly represented in the police, judiciary, magistracy and Her Majesty’s Prison Service. To counteract this lack of ethnic diversity in the workforce, the Young Review urged pro-active efforts to include organisations and representatives from the offenders’ communities and faiths so as to tackle unequal outcomes.

Meanwhile, the proportion of foreign nationals in jail (12per cent) has remained fairly stable since 2002. However, they are now much more likely to be Polish (10per cent of imprisoned foreign nationals) or Romanian (7per cent).

Reforms to civil law justice, such as reductions in the availability of legal aid, are also expected to affect ethnic minorities more than others, in part because people in these communities tend to be more reliant on legal aid financial support. IN addition, many types of immigration and housing cases relevant to BAME groups and Roma are now ineligible for public funding. The Equality and Human Rights Commission (EHRC) has also argued against fees for employment tribunals, on the basis that it compromises certain groups’ human rights by restricting access to justice. This argument is supported by the fact the number of claims relating to both race and religion or belief have dropped by 61 per cent since the introduction of these fees. Monash University’s Access to Justice: A Comparative Analysis of Cuts to Legal Aid similarly noted that BAME lawyers were disproportionately represented among those practising in the legal aid sector, and so the cuts could be expected to make the legal profession less diverse.

Education

In England improved attainment among both south Asian and black minority students resulted in a narrowing of the gap with white pupils in state schools between 2008 and 2013. However, this change is less marked in Wales and Scotland. Meanwhile gypsy and traveller pupils continue to have the lowest attainment levels of any ethnicity. Furthermore, children from socio-economically disadvantaged backgrounds in England tend to have lower attainment. Although this discrepancy is most pronounced among white boys eligible for free school meals, it is also marked among Asian, black and mixed students.

Individuals of Indian, mixed or Caribbean/African/black origin are significantly more likely to hold a degree-level qualification than those from white, Pakistani or Bangladeshi backgrounds. This trend is set to continue as a greater proportion of minority ethnic school leavers now go on to higher education, outstripping the white majority. In particular, 19-20 per cent of mixed and Asian pupils went to top British universities in 2012/13, compared to 15 per cent of white students. In contrast, only 13 per cent of Black pupils went to study at universities ranked in the top third. The proportions of Buddhists, Hindus, Sikhs and Jews with degrees (or equivalent) were also higher at over 48 per cent than the same share for Muslims (28 per cent) or Christians (25 per cent respectively).

Employment and income

Austerity measures under both the David Cameron and Theresa May governments have hit ethnic minorities (alongside women and people with disabilities) the hardest, although it is worth noting that the impact has not been uniform across ethnic groups: Chinese, Indian, Black African communities were affected more than Bangladeshi and Pakistani households. From the outset, the Equality and Human Rights Commission (EHRC) was critical of the government for failing to consider how austerity politics would impact minority groups. However in 2012 the government cut ERHC funding by more than half and stripped it of its duty to foster ‘a society with equal opportunity for all’.

Approximately two-fifths of people from ethnic minorities currently live in low-income households (twice the rate of white families). This statistic again varies across groups: more than 50 per cent of families of Bangladeshi and Pakistani origin live in low income households, compared to less than 30 per cent of Indian origin. Research by Alison Donald at Middlesex University attributes the disparity between the White British majority and minorities to the age structure of BAME groups, work status and higher rates of in-work poverty. She also points to changes to social security as penalising the poorest in society to a much greater extent that the richest.

Pay has decreased across the board since 2008 but white workers continue to get paid 50 pence more per hour than the combined average of BAME workers. The African/Caribbean/black community has been hit particularly hard by the recession, with a £1.20 decrease in average hourly pay. The Sikh community was hardest hit by wage decline following the crash, with a fall of £1.90 in average hourly pay. The TUC has identified a 23 per cent pay gap between black and white graduates, with the gap for those educated to GCSE level at 11per cent.

Employment rates continue to be higher for the White majority than for ethnic minorities (75 per cent compared to 59 per cent). In 2015, analysis released by the Labour Party indicated that there had been a 49 per cent rise in long-term unemployment among 16-24 year olds from BAME groups since 2010. In contrast, youth unemployment among young white people fell by 2 per centage points during this period. These findings were corroborated by the EHRC who found Pakistani/Bangladeshi women were less than half as likely to be in employment as the average UK woman. The study also found that Muslims experienced the highest unemployment rates and lowest hourly pay, while Jews have experienced the highest fall in employment rates of any religious group since 2008.

A large-scale survey conducted by Business in the Community indicated that bias against BAME minorities in the workplace persists, with extensive evidence of racial harassment, underrepresentation at every management level and barriers to opportunity despite greater ambition to progress. Campaigners have called for the government to show the same commitment to tacking ethnic inequality as they have to addressing gender imbalance, for example by pushing to increase the diversity of FTSE 100 boards.

This post gives the views of the authors. It does not represent the views of the London School of Economics or the LSE Public Policy Group.

Sonali Campion is Communications and Events Officer at the LSE’s South Asia Centre and a former editor of Democratic Audit.

Ros Taylor (@rosamundmtaylor) is Managing Editor of Democratic Audit.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.