Audit 2017: How effectively is gender equality achieved in the political and public life of the UK?

As part of the 2017 Audit of UK Democracy, Sonali Campion and the DA team examine the extent to which gender equality provisions in British public life accord with democratic requirements. Where previous historical inequalities and discrimination against women are being rectified, is the pace of recent change fast enough?

MP Stella Creasy high-fives fellow MP Jess Phillips as Anna Soubry and Jo Johnson look on. Photo: University of Nottingham via a CC-BY-NC-SA 2.0 licence

This article was published as part of our 2017 Audit of UK democracy. We have now published: The UK’s Changing Democracy: The 2018 Democratic Audit with LSE Press, available in all ebook formats. You can download the whole book for free, and individual chapters, including a fully revised version of this article.

What does democracy require in terms of gender equality?

- Men and women must enjoy genuine equality in terms of civil rights (covering equal pay, employment rights, property rights, access to legal protections, childcare access, and marriage and partnership laws)

- In particular, political and public life should be organised to maximise the equal chances of women and men to be involved in democratic politics – to vote and stand for election, to take part in party and political processes, to contribute to public debate and discussion, and to rise to the top in elected public office.

- Employment in the public service sector (and in firms working on public sector contracts) should serve as exemplars of good practice in improving gender equality more broadly.

- No gender group (male, female or transgender) should be subject to differential discrimination in political or public life, nor to prejudicial or demeaning discussion in terms of public and media discourses.

- Where barriers to gender equality are proven to exist, it is desirable for public regulation or interventions to at least temporarily be undertaken to secure appropriate and feasible ameliorative actions (consistent with maintaining the civil rights of all citizens).

Recent developments

Although equal pay legislation for men and women was first passed in the UK in 1970, a substantial pay gap still persists for full time workers. Career parity remains very difficult to achieve for women with caring responsibilities. Systematic efforts to improve the proportion of women in public life are much more recent, and they have not been effectively backed by statutory powers or firm regulation. For instance, political parties are not obliged to seek gender parity in the candidates they put before voters, only to not discriminate against women. The representation of women in some public roles (like being an MP or a member of a devolved assembly) has improved significantly in the last five years. The prime minister, Scottish First Minister and leaders of Plaid Cymru and the Democratic Unionist party are all female. However, we remain a long way from achieving parity of representation for women in public life. Furthermore, some new social developments, such as the use of social media to let citizens comment on the behaviour of politicians and others in the public eye or the focus of media attention, have shown disturbing indications of entrenched misogynistic attitudes among substantial groups of citizens. Similarly, although more transgender people are visible in public life, there remains substantial prejudice against them and the Gender Recognition Act 2004 needs updating to reflect the principle of gender self-declaration.

Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities, Threats (SWOT) analysis

| Current strengths | Current weaknesses |

|---|---|

| The proportions of women in politics, public life and the upper levels of the business world have improved noticeably, albeit often from a low initial base (see below). | There is still a pervasive gender bias across the board and the overall pace of change in achieving gender parity shows that existing or ‘legacy’ ways of operating still restrict women’s full participation. For instance, with less than two fifths of party members being women it has been hard to get local selectorates in some parties (like UKIP and the Conservatives) to choose women candidates. |

| There is now broad public consensus that achieving an equal gender balance is desirable. This is reflected in increased efforts by both the public and private sectors, for example, to promote diversity in their recruitment processes; offer more family-friendly policies such as flexible working hours; specify clear diversity targets and make people accountable for achieving them; and offering tailored mentoring and support for women to progress within organisations. | In tabloid newspapers and other popular media women in public life continue to be treated in unfair ways, e.g. judged on their appearance (the infamous 'Legs-it' Daily Mail cover) or family roles. |

| After many years of irresolute and piecemeal action, most of the main political parties are working harder to promote women, particularly in Westminster and the devolved assemblies. The commitment is reflected by the growing use of gender quotas among parties that lean to the left. | The recent growth of social media has shown shocking incidents of misogynistic behaviour. Women politicians or participants in public debate (such as those advocating for more women on UK banknotes) have been harassed by virulent ‘trolls’. Police/court action has been prompt, but confined to a few cases. |

| Using demeaning language about women, or harassing them in the workplace, has clearly become publicly unacceptable and political suicide for politicians. Social media vigilance has increased the level of scrutiny of such issues, previously often swept under the carpet. | Elite behaviours also still show traits that are off-putting for women, such as the frequent raucous behaviour of MPs at question time in the House of Commons. Women are judged negatively for behaviour accepted or even encouraged among men. Credibility is more easily presumed among men, whereas women have to work harder to earn it. In politics and in the workplace, masculine styles of thinking and working are often represented as more ‘natural’. |

| Transgender people continue to suffer discrimination and prejudice. |

| Future opportunities | Future threats |

|---|---|

| As women become better represented in public life, and the engagement with gender inequalities becomes more sophisticated and far-reaching, there is potential for greater changes towards ‘feminising’ institutional cultures and practices. | There is a danger of complacency, of seeing intractable issues as resolved, when many years work may still lie ahead. |

| With Labour leading, parties are adopting quotas and other activist methods to boost women’s representation. | Recent experience with social media; the escalating growth of pornography adversely affecting youth attitudes to women; problems such as honour killings, forced marriages, and female genital mutilation among some ethnic minority populations; and continued incidents of sexist behaviours in the media and public life – all show that UK social trends are not all favourable for gender equality. |

| There are now more women than men in the civil service and more women than men are joining the legal profession every year. In the future a larger pool of eligible candidates should therefore be available for senior roles. | Public sector austerity and government spending cuts have hit women harder than men and increased relative disadvantage in ways that reduce incomes and childcare support, and may cut back women’s employment and opportunities more broadly. |

| Transgender people are gaining more exposure in public life. |

Women’s representation in UK public life

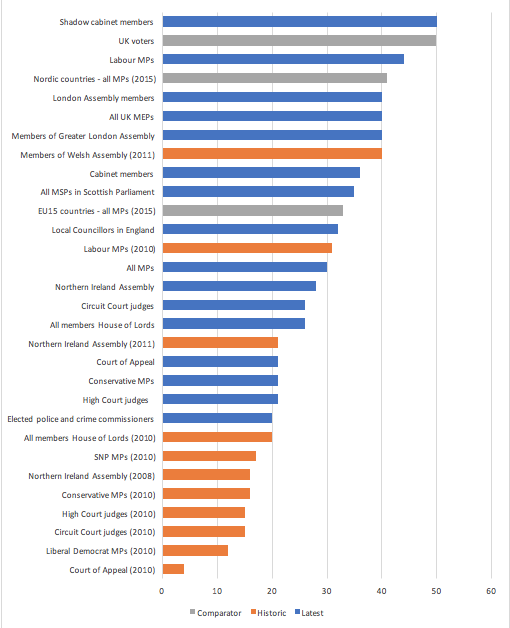

Everywhere in UK public life women still remain a minority, despite constituting half of the electorate. The Welsh National Assembly in the early 2000s is the only public body in UK history where gender parity was achieved, and this ratio did not endure. Chart 1 shows that in 2016 there still sharp differences in the extent which women have been able to break into positions of political power or seniority within the public services.

In 2016 fewer than a quarter of Court of Appeal and High Court judges and Conservative MPs are women – illustrating the very long UK time spans for changing historic patterns of women’s under-representation. Chart 1 also shows some data for recent past years and by comparing the two dates readers can gauge the degree of changes achieved since 2010 or thereabouts – e.g. the Court of Appeal moved from having one in 25 female judges to having one in five.

Chart 1: The proportion of women in a range of major roles in UK public life, in 2016 and a recent past date

More women have become MPs recently in a large part because most of the main parties fielded more female candidates than they did in 2010, and both the Tories and Labour placed women in winnable seats. For example, the Conservatives ran female candidates in 38% of retirement seats and Labour put 53% of women candidates in winnable seats. Labour’s strong improvements have been attributed to using all-women shortlists (AWS). The Conservatives remain resistant to gender quotas and even the ‘A-list’ system to increase the diversity of Tory MPs in 2010 was not used in 2015. UKIP has a huge majority of male candidates still, and in Northern Ireland only 25% of candidates for MP were female. The Democratic Unionist Party (DUP) did not field any women at all.

David Cameron fulfilled his promise that one third of his cabinet would be women by 2015, in contrast to previous Conservative-majority Cabinets, which had a maximum of two women. Theresa May’s cabinet is 36% female. Labour’s Shadow Cabinet has consistently comprised 40% women and for the first time achieved and maintained gender parity following the 2016 reshuffle, despite numerous changes of personnel.

In the devolved assemblies, the proportion of female MSPs in Scotland has been significantly better than Westminster. But recent patterns across three main Scottish political parties (SNP, Labour and the Lib Dems) point to either a stalling or falling in the number of women MSPs elected since 2003. On the flipside, positive changes have come both from the top down, through party rules, and the bottom up, through the civic awakening that accompanied the referendum. The SNP, Scottish Labour and the Scottish Conservatives are now all led by women. Nicola Sturgeon in particular has pushed for the SNP to use quota measures with some success, and Labour has pledged that 50% of its Holyrood candidates will be women. Encouragingly, EU-wide research suggests that fears voters are put off by female candidates are unfounded.

Employment and income

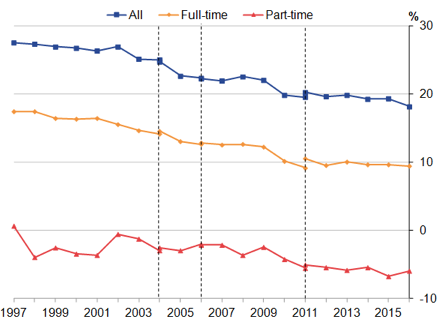

In wider UK society, Chart 2 shows that the gender pay gap for median earnings of full-time employees (showing how much better paid men are than women for the same work) currently stands at 9.4%. The gap is now the lowest it has ever been, but the pace of change has been slow since 2011 – for instance, the gap actually increasing by 0.5% between 2012 and 2013. Women in part-time work, however, earn 6% more than their male counterparts and their rates of part-time pay have exceeded men’s since 1998.

Chart 2: The gender pay gap for median gross hourly earnings (excluding overtime), UK, April 1997 to 2016

Source: Office for National Statistics, Annual Survey of Hours and Earnings. Notes: Earnings excludes overtime. Full-time defined as >30 paid hours per week. Dashed lines represent discontinuities in the 2004, 2006 and 2011 estimates; 2016 data provisional. The data shown are for April in each year.

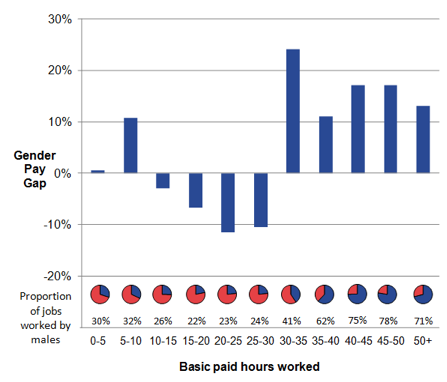

Women’s labour market participation, pay and conditions are linked to the amount of support they receive for their caring responsibilities. On average British women do about twice as much as childcare as men, and factors such as a lack of affordable childcare inhibit women’s ability to sustain full-time, better-paid employment. Chart 3 shows that the full-time pay gap varies according to age group: women in their twenties tend to earn slightly more than their male counterparts. It is during their thirties, when women are now more likely to be having children, that the gap begins to grow. New rules to make parental leave more flexible for both partners are a step in the right direction, but while the discrepancy between male and female earnings persists, uptake is likely to be limited.

Chart 3: Gender pay gap for median gross hourly earnings (excluding overtime) by age group, UK, April 2016

Source: As Chart 2. Notes: Earnings data exclude overtime. The ‘all employees’ pay gap is wider because more women are part-time than men.

Welfare cuts introduced since 2010 have disproportionately affected women. Women are statistically more likely to use public services, to be single parents or carers for older or disabled relatives, and to live longer and therefore need greater support in later life. Women’s average losses from changes to tax credits, housing and child benefits were twice as large as men’s as a proportion of net individual incomes, with the lowest earners hit hardest. Furthermore, women make up the majority of public sector workers, so cuts to public services and pay freezes there are also impacting women’s employment.

Cultural barriers to change

Quotas and other policies to promote female participation in the workplace are welcome developments and fall into line with the UK’s commitments under CEDAW to take all appropriate measures, including legislation and temporary special measures, so that women can enjoy their human rights and fundamental freedoms fully.

However, the majority of these measures treat women as the problem, rather than tackling the bias that has restricted their involvement up until now. A recent LSE report Confronting Gender Inequality focussed specifically on gender imbalances in the economy, politics, law and the media – and recommended much wider measures. These include designing macroeconomic policies which value the reproductive sector and unpaid care work; gender budgeting; applying equality legislation more effectively; improving women’s access to justice; monitoring and reporting on gender representation in the media; and efforts to educate people on the root causes of gender inequality across the public and private sectors and at all levels.

With transgender people more visible in public life, the discrimination and obstacles the trans community faces have received far more scrutiny. The Gender Recognition Act 2004 and Equality Act 2010 should be revisited in the light of these findings.

Conclusion

Women are now more present and visible than ever before in UK politics and public life. However, the pace of change is slow, and men continue to dominate the most senior roles across the board. Furthermore, it seems debatable whether institutional culture and attitudes are evolving as rapidly in Britain as elsewhere. Between 2007 and 2016 the UK slipped from 13th to 20th in the World Economic Forum’s Global Gender Gap Index. If gender imbalances are to be tackled effectively and in a lasting manner, a much more holistic approach is required.

This post is part of the 2017 Audit of UK Democracy. It does not represent the views of the London School of Economics or the LSE Public Policy Group.

Sonali Campion is Communications and Events Officer at the LSE’s South Asia Centre and a former editor of Democratic Audit. She tweets @sonalijcampion.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

[…] major changes in gender representation, the UK continues to exhibit large disparities in power and representation between men and women. Here, Nicola Lacey shares findings from the […]

[…] our recent Audit of Democracy post by Sonali Campion and the DA team showed, the UK continues to exhibit large disparities in power and representation between men and […]

[…] terms of wider social diversity, the 2015 parliament is in some ways (notably gender and ethnicity) the most diverse and representative ever. Yet Campbell et al write: ‘To put the […]

‘Everywhere in UK public life women remain a minority’ Interesting research by .@democraticaudit https://t.co/7DRJUJBK71 #LoveYourVote

How effectively is gender equality achieved in the political and public life of the UK? https://t.co/5lTC5NTski

How far is gender equality achieved in UK political and public life? Some progress, but still lots to do. https://t.co/d3COVnK3N5

I fed into @democraticaudit’s 2016 Audit of UK democracy, looking at gender in public & political life. Read here: https://t.co/GpeJvx3YLG

How effectively is gender equality achieved in UK political and public life? https://t.co/aq5pwBsE93

How effectively is gender equality achieved in the political and public life of the UK? https://t.co/d3COVnK3N5

How effectively is gender equality achieved in the political and public life of the UK? https://t.co/RK03L9aezV

How effectively is gender equality achieved in the political and public life of the UK? https://t.co/tHJ7gGSsgp

How effectively is gender equality achieved in the political and public life of the UK? https://t.co/r3WoYPlukG

How effectively is gender equality achieved in the political and public life of the UK? https://t.co/nYnAF8qPWQ https://t.co/84keI0lMmo

Via @democraticaudit – How effectively is #genderequality achieved in UK public life? (Spolier : could do better) https://t.co/bq3vNHrK77

Good post on ‘How effectively is gender equality achieved in the political and public life of the UK?’. https://t.co/fw3LiTM1iB

How effectively is gender equality achieved in the political and public life of the UK? https://t.co/Ie02wAjxue https://t.co/gV9D74C1B3