Audit 2017: How far does the growth of social media extend or threaten democratic processes and values? Does it foster or impede greater citizen vigilance and control over government?

Social media technologies (such as blogging, Facebook, Twitter, Google, YouTube, Snapchat and Instagram) have brought about radical changes in how the media systems of liberal democracies operate. The platform providers have become powerful actors in the operation of the media system, and in how its links to political processes operate. Yet at the same time these companies claim political neutrality, because most of their content is created by their millions of users – perhaps creating far greater citizen vigilance over government and politicians. As part of our 2017 Audit of UK Democracy, Ros Taylor and the Democratic Audit team look at how well the UK’s social media system operates to support or damage democratic politics, and to ensure a full and effective representation of citizens’ political views and interests.

At the ‘Rally to Restore Sanity / March to Keep Fear Alive’ on the National Mall, Washington DC, 2010. Photo: Adam Fagen via a CC-BY-NC-SA 2.0 licence

This article was published as part of our 2017 Audit of UK democracy. We have now published: The UK’s Changing Democracy: The 2018 Democratic Audit with LSE Press, available in all ebook formats. You can download the whole book for free, and individual chapters, including a fully revised version of this article.

How should the social media system operate in a liberal democracy?

- Social media should clearly enhance the pluralism and diversity of the overall media system, especially by lowering the costs for citizens in securing political information, commentary and evidence, and improving their opportunities to understand how democracy works. Any adverse by-product effects of social media use on established or paid-for journalism and media diversity needs to be taken into account. ‘Disintermediation’ (‘cutting out the middle man’) processes that simply reduce the viability of existing media (like terrestrial broadcasting and print/paid-for newspapers) may have net negative effects on the overall media system.

- Social media should be easily accessible for ordinary citizens, encouraging them to become politically involved by taking individual actions to express their views, or collective actions with others to promote a shared viewpoint.

- The overall media system created should operate as transparently as possible, so that truthful/ factual content predominates, truthful content quickly drives out incorrect content, and ‘fake news’, ‘passing off’ and other lapses are minimised and rapidly counteracted.

- The overall growth of social media should contribute to greater political equality by re-weighting communication towards ordinary members of the public and non-government organisations, cutting back the communications, nodality and organisational advantages otherwise enjoyed by corporate actors, professional lobbyists or ‘industrialised’ content promoters.

- By providing more direct, less ‘mediated’ communications with large publics social media should enhance the capacity of politicians and parties to create and maintain direct links with citizens, enhancing their understanding of public opinion and responsiveness to it.

- Social media should unambiguously enhance citizen vigilance over state policies and public choices, increasing the ‘granularity’ of public scrutiny, speeding up the recognition of policy problems or scandals, and reaching the widest relevant audiences for critiques and commentary on different government actions.

- Platform providers argue that they do not generate the content posted on millions of Twitter sites or Facebook pages, but only provide an online facility that allows citizens, NGOs and enterprises to build their own content. However, because these large companies also reap important network and oligopoly effects that increase their discretionary power, they must be regulated to prevent their behaving destructively towards established media systems, or abusing their advantages over other media companies or citizen behaviours that breed dependence upon them.

- Platform providers must take their legal responsibilities to ‘do no harm’ seriously, and respond quickly to mitigate new social problems enabled by social media that are identified by public opinion or elected politicians.

- In assessing (and potentially regulating) social media effects, evidence-based knowledge of the actual, empirical behaviours of users and platform providers is key, rather than relying on a priori expectations.

- The development of regulations and law around fast-changing ‘new goods’ like social media often lags behind social practice. Legislators and government need to be agile in responding to emergent new problems created by social media, or to existing problems that are re-scaled or change character because of them. Where existing controls and mitigation actions are already feasible in law, their implementation needs to be prioritised and taken seriously by busy police forces.

- As with conventional media, citizens should be able to gain published corrections and other effective forms of redress (including appropriate damages) against reporting or commentary that is illegal, unfair, incorrect or invades personal and family privacy. Citizens are entitled to expect that platform companies will respect all laws applying to them in speedily taking down offensive content, and will not be able to exploit their power to deter investigations or prosecutions by the police or prosecutors.

The growth of social media – and its wider consequences for the web – have been seen in rather different ways. On the one hand, easy to produce content and low-cost internet communication helps citizens in myriad ways to organise, campaign, form new political movements, influence policy-makers, and hold the government accountable. Social media can also ‘disintermediate’ the conventional journalist-run and corporate-owned media. In 2008, Clay Shirky’s Here Comes Everybody set out a vision in which self-publishing meant ‘anyone can be a journalist’. Yashcha Mounk points out that social media ‘favours the outsider over the insider, and the forces of instability over the status quo’.

A populist discourse rationalising such changes argues that the mainstream media (‘MSM’) has stifled debate on issues that matter to ‘ordinary’ citizens. This pattern was observable in the EU referendum campaign (when the Leave campaign derided ‘expert’ opinions and urged people to ‘take back control’) and in the United States (where Donald Trump sought to bypass most media outlets in favour of direct communication at rallies and on social media). Some left critics also share the sentiment. Citing the LSE’s study of negative representations of Jeremy Corbyn in the British press, Kadira Pethlyagoda describes a ‘chasm between the masses and the elites, represented by the out-of-touch MSM, [that] threatens not only democracy and justice, but also stability’.

On the other side of the debate, new social goods, especially those that disrupt the established ways in which powerful interests and social groups operate, often attract exaggerated predictions (or even ‘folk panics’) about their adverse implications for society. Social media inherently present a double aspect, because they are run by powerful platform provider corporations (Facebook, Twitter, Google, and WhatsApp). Many seek to ‘wall in’ millions of users within their proprietary domains. Yet at the same time almost all the content they carry is generated by their millions of users, using free speech rights to communicate about the issues that matter to them. So while the platform providers might seem oligopolistic in the way that they carve up the social media market, and in the enormous corporate power they have acquired relative to other companies, especially conventional media corporations, they can still claim to be politically neutral and competing bitterly for customers – hence standing outside conventional media regulation provisions.

Recent developments

In the realm of news and current affairs, the recent growth of social media in the UK has shrunk the audience for free TV bulletins. For the BBC, the change means UK viewers can watch and consume TV news on PCs or smartphones, without paying the licence fee. At the same time, the readerships of most paid-form/print daily and Sunday newspapers has also fallen, although some Sunday titles and the free Metro are exceptions. Newspaper publishers must either rely on existing readers recommending their content, or pay to advertise on social media – even as digital advertising revenues fail to live up to publishers’ hopes. Thus social media are widely seen by journalists and others as posing an existential challenge for legacy publishers. (See our chapter on the ‘mainstream’ media system).

For a growing proportion of people, particularly among the 18-34 year-old demographic, online news reports represent their chief source of news. While many people use apps to follow the news, a growing number rely on stories shared via Twitter and, in particular, Facebook.

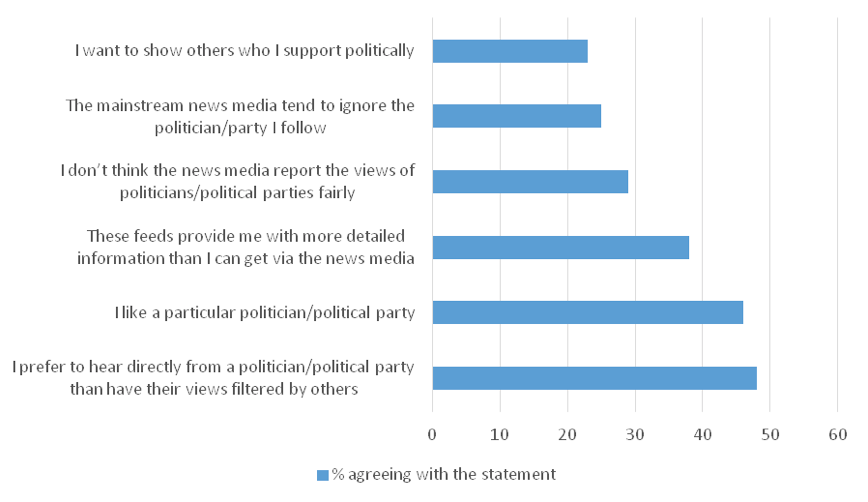

Chart 1 also shows that people value the ability to directly monitor what their political representatives and candidates are doing, and social media offers an easy way to do so. Currently 18 per cent of all UK citizens follow a politician. In the case of councillors or even MPs, social media commentary is often the first thing to draw politicians’ attention to causes and public concerns that do not reach the constituency surgery, council meeting or email inbox. The ability for people to click their concurrence and comment in their own terms helps indicates the breadth and depth of public feeling on a particular issue.

Chart 1: Why people follow politicians on social media

Notes: Question was: ‘You say you follow a politician or political party via social media, what are some of the reasons for this? Base: All who follow a politician or political party on social media: USA, UK, Germany, Spain, Ireland, and Australia = 2671.

Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities, Threats (SWOT) analysis

| Current strengths | Current weaknesses |

|---|---|

| Voters can follow their elected representatives on social media, and candidates who are competing against them. By replying and commenting, people have low cost opportunities to contact and influence them at a national or local level. | Platform providers give people the ability to customise the news they receive on social media. Most people use this facility as they use conventional media, paying most attention to viewpoints and sources with which they already agree. On tailored social media responding closely to citizen preferences, this behaviour can create a ‘filter bubble’ in which opposing or even unaligned voices go unheard. Only 4%of social media users follow politicians from both the political left and right. |

| Even citizens unaffiliated with an organisation, can quickly disseminate their message to a very wide audiencevia social media and have some chance of evoking wider agreement from like-minded people – a dynamic that drives retweeting, FB ‘likes’ and even now officially recognised online petitions to the UK government. The popularity of social media among young people provides a helpful means of encouraging them to get on the electoral roll, after the relative success of the National Voter Registration Drives. | Because most retweeters and ‘likers’ are not professional journalists on fact-checked publications, but ordinary citizens with lower levels of information, critics argue that inaccurate and misleading information (‘fake news’) can spread more quickly. For example, after the Grenfell Tower disaster online reports spread quickly that the government had issued a D-Notice restricting media reporting on the issue, which (of course) it had not. |

| Digital-only publication and dissemination via social media have lowered the start-up costs for many alternative media outlets, broadening the range of professionally produced news and commentary available to citizens. Snapchat Discover has enabled mainstream publications like Le Monde and CNN to reach the 18-24 year-old audience more easily (10% reach in the UK) as legacy broadcast and printed press consumption declines. | Digital-only publishing by highly committed or partisan publishers has also enabled them to exploit ‘data-industrial’ capabilities to flood online platform systems with multiple biased or untrue messages in ways that are completely un-transparent. For instance, the ongoing American inquiries into the Trump administration’s links with Russia have revealed the ability of foreign powers to use ‘fake news’ disseminated on social media to sway the political process. |

| New social media are nominally free to set up and use, and quite sophisticated media like blogs are very cheap to run. Hence the growth of social media unambiguously expands the foundations for a pluralistic and diverse media system. | There is evidence that online abuse and harassment, particularly of women, children and minorities, can be more extensive in social media than in society outside. Moving online increases the audiences for abuse, lets it occur in real time and more often, escalating faster, and often involving extreme language. Online ‘hate speech’ is illegal in the UK but police and prosecutors have been slow to engage. Some cases of legal redress for defamation on Twitter have been successful , but this is a very costly process to accomplish. Many people complain that platform providers have been too slow to take down offensive, harassing or illegal content. So a lack of online ‘civility’, and harassment of vulnerable people, remain a serious problem. |

| Current opportunities | Future threats |

|---|---|

| The growth of fact-checking tools and websites, including automated fact-checking, enables rapid rebuttal of falsehoods – especially if platform provider firms assist in the process. This ability improves with time. | The media landscape risks atomisation as citizens turn to specialised or hyper-local news sources (but see below), with a corresponding decline in the political salience (‘valence’) of top media issues. |

| Social media enables rapid and unprecedented scrutiny of policymaking and politicians’ pronouncements, with stakeholders’ and experts’ opinions freely available on Twitter – but while some liveblogs have tried to curate them, this body of knowledge and input remains diffuse and rarely linked to formal mechanisms, such as select committees of the House of Commons. | Armed with huge cash reserves (often gained from setting up complex tax-avoidance schemes), the giant corporations have diversified into social media conglomerates. Facebook (which owns Instagram), YouTube (owned by Google) and to a lesser extent Twitter, now dominate social media platforms. These corporations’ power to shape how democratic discourse happens online is considerable, and almost unregulated at nation state level. |

| Outside the UK and US, growth in social media appears to be levelling off in favour of the more closed environment of messaging applications. | |

| The European Commission (EC) has the population scale and legal resources to move vigorously against misuse of monopoly power by Microsoft (after it bundled its Explorer browser and stifled competition) and later by Google (over unfairly advantaging its own search engine hits). In mid-2017 the EC fined Google 2.4bn euros, a substantial disincentive to monopolistic practices. After Britain leaves the EU, it is unclear whether any UK government would have the motivation, legal resources or scale to act as vigorously. Even if rulings were made, the UK is a much smaller and less salient market for these firms than the EU as a whole. |

How social media users behave

Many social media critics rest their objections on claims that they change the behavioural dynamics of information markets in adverse ways. The ability to ‘like’ and ‘follow’ like-minded individuals on social media, together with Facebook’s use of algorithms that present news and posts based on a user’s existing preferences, has led to fears that people increasingly obtain their news from a self-reinforcing ‘filter bubble’ of similar opinion. On the day after the Brexit referendum the web activist (and ‘remainer’) Tom Steinberg posted:

‘I am actively searching through Facebook for people celebrating the Brexit leave victory. But the filter bubble is SO strong, and extends SO far into things like Facebook’s custom search that I can’t find anyone who is happy despite the fact that over half the country is clearly jubilant today and despite the fact that I’m actively looking to hear what they are saying’.

Relatively few social media users will ever look outside their bubble, and they may not now be able to ‘pop’ it and reach broader views, even if they wanted to.

In the social media world, the key metric of successful content is its ability to generate retweets or FB ‘likes’. Chasing the advertising revenue that a ‘viral’ piece or video can generate has led some media publishers to produce ‘clickbait’ – sensationalist headlines that tempt the readers to click through to that story in preference to others on the page. While a great deal of clickbait content is celebrity or lifestyle journalism, some of it relies on distorted and sensationalised news stories. The editor of the Guardian describes this practice as ‘chasing down cheap clicks at the expense of accuracy and veracity’.

Fake news

The term ‘fake news’ is inevitably subjective and contentious. In some instances it is difficult to draw a clear line between the kind of partisan reporting long apparent in the British media and fabricated stories. Ulises Mejias argues that to insist on a clear distinction between ‘real’ and ‘fake’ news ‘bypasses any kind of analysis of the economics that makes disinformation possible and indeed desirable’ in Western democracies. However, as discussed in our media chapter, increasingly globalised media ownership has opened up opportunities for powerful actors and state-funded operations to influence democratic debate abroad. Leaked US intelligence which claims Russia used online fake news to influence voters suggest that the phenomenon is a growing threat to the legitimacy of elections in the West. In his analysis of electoral manipulation across the world, Ferran Martinez i Coma notes a move away from ballot-stuffing and towards media manipulation. The chairman of the Commons Select Committee for Culture, Media and Sport has described fake news as ‘a threat to democracy’ that ‘undermines confidence in the media in general’. One notable development in the UK has been the ability of far-right groups such as Britain First to disseminate their message on social media under the guise of entertainment.

Threats to female politicians and activists

Misogyny on social media remains a problem (Demos), despite the introduction of stricter rules by Twitter. The MPs Yvette Cooper, Jess Phillips, Stella Creasy, Diane Abbott and Anna Soubry have also reported misogynistic and racist abuse. Social media harassment has been the subject of numerous other complaints by female politicians and activists, especially at the 2017 general election. A 2016 Demos study suggests that women users are equally as responsible as men for originating misogynist threats. In 2014 a man and a woman were given prison sentences for threats posted on Twitter to feminist campaigner Caroline Criado-Perez. ‘Trolling’ and ‘stalking’ women or ethnic minority politicians clearly inhibits their freedom to develop and express opinions and debate on Twitter and other social media, and so represent a threat to democratic discourse online. Other forms of misuse of social media – such as the bullying of vulnerable school students by others – can easily have tragic consequences. Yet while the effective regulation of the new media spaces to outlaw hate speech is clearly important, platform providers (many of whose founders espoused socially libertarian ideas) have frequently been reluctant to self-regulate their content effectively, and help state authorities do so externally (except in the case of clearly illegal material, such as encouraging terrorism or promoting suicides).

Hyper-local social media

A more positive trend has been the development of hyperlocal news models, which may partly offset the rapid decline of paid-for local newspapers across the UK. The new approaches continue to evolve, with the ease of making micro-payments offering the possibility of a revenue stream (albeit not necessarily an easy or sustainable one).

Nor are hyper-local media necessarily amateurish. Around half of the citizens producing hyperlocal news across the UK have some form of mainstream journalistic experience. Andy Williams notes that hyperlocal news usually privileges the voices of community groups and members of the public, whereas the traditional local press ‘are very authority-oriented in their sourcing strategies’. But most outlets depend heavily on volunteers: ‘Despite the impressive social and democratic value of hyperlocal news content, community news in the UK is generally not a field rich in economic value’. So he concludes that for all their valuable efforts, unpaid and part-time news producers ‘can only very partially plug growing local news deficits’. A Cardiff University initiative has sought to support hyperlocal and community journalism by offering online training and funding advice, chiefly in Wales, where it has identified a particular democratic deficit. The scope for supporting hyperlocals through training and funding initiatives such as audience co-operatives is considerable.

Conclusions

Social media clearly offers unprecedented opportunities for voters to debate and scrutinise public policy, albeit on terms heavily conditioned by platform providers, and in a constant ‘arms race’ with the development of industrialised/professionalised social media campaigning by companies and large vested interests. For good – and sometimes ill – social media allow politicians to communicate directly with citizens, enthusing the electorate and reinforcing their bond with supporters. As a tool for influencing and holding the political class accountable for their actions, it may ultimately prove as powerful as the press itself, which increasingly relies upon social media channels to reach younger people.

The blooming of multiple voices enables those who have traditionally been on the fringes of debate, such as disabled citizens, to make their voices heard. However, it also opens a channel for extremists and news outlets with motives going far beyond conventional partisanship to embrace attempts to skew and undermine democratic debate itself. Because of the ability of users to choose whom they follow and exclude unwanted or dissenting voices, some critics see social media as lending itself to conspiracy theory and fake news. The fact that strongly-held (sometimes abusive) opinions are so visible on social media risks alienating people from the ‘normal’ political process and increasing social polarisation, undermining political valence.

So it is questionable whether the current main platforms are fit for purpose either in terms of the transparency of their monitoring policies (and the extent to which they co-operate with governments for security purposes), or their ability to foster democratic deliberation and thoughtful social learning. The hegemony and ubiquity of these platforms may be nudging people towards new kinds of political behaviour that will only become fully apparent in years to come.

This post does not represent the views of the LSE.

Ros Taylor (@rosamundmtaylor) is editor of Democratic Audit and co-editor of LSE Brexit. She is a former Guardian journalist and has also worked for the BBC.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

… [Trackback]

[…] Informations on that Topic: democraticaudit.com/2017/08/07/audit-2017-how-far-does-the-growth-of-social-media-extend-or-threaten-democratic-processes-and-values-does-it-foster-or-impede-greater-citizen-vigilance-and-control-over-government/ […]

The concept that mainstream media does not have bias or consults a vast reference library to ascertain the correct facts of a story can be clearly disproved by any brief study of recent economic, social and political events. These players we are told tell the truth, get it right. yet, SM has been ahead of the biased media on so many issues one can only deduce MSM has it’s own agenda in the bubble it shares with the elites. I am all in favour of classes to teach SM commentators how to best argue their case, but not for the idae they are changed into MSM apologists.