Evidence from Australia: women are under-represented in senior political appointments, and this affects the representation of women in parliament

Political advisers can help shape public policy. They are also often the politicians of the future, so it matters who they are. Using a unique data resource from Australia, Marija Taflaga and Matthew Kerby tracked men’s and women’s differing career trajectories in Australian government over time, and found that men were more likely to reach senior levels, and then more likely to enter parliament.

Senior political advisers during the Obama White House. Picture: Obama White House/US government work

If you’re a political obsessive you’ll be familiar the backroom figure of the ‘political adviser’. In popular culture we’ve become accustomed to this character: the foul-mouthed Malcolm Tucker from The Thick of It or Veep’s the rather disgusting Jonah. If you’re an optimist about politics, maybe you recall C. J. Cregg or Toby Ziegler from The West Wing. In most of these examples, these characters operate at the heart of power and are central to getting things done. The underlying message is that political staff are pivotal to the world of politics and may actually have a better idea of what’s going on than their political masters.

In the real world, researchers have discovered that political advisers are more than fixers and bagmen. They have become an institutionalised part of the executive wing, responsible for policy-making and delivering outcomes.

Who political advisers are matters

Given the work that political advisers undertake, it is important to understand their career pathways. One reason why this matters is because we know from research that who occupies key decision-making roles impacts policy outcomes. It does make a difference if people from minority backgrounds have both enough resources and discretion over policy decisions – and this applies for women as well.

Another reason is that there is growing evidence that political advising is an important stepping-stone for a career into parliament. Political advisers gain experience of policy-making, political life and the chance to build up networks within their parties, which may make them attractive candidates to internal party selectors.

As political scientists we know there are significant barriers facing women getting into politics. Women are less likely to consider themselves as good political candidates, are less likely to run and less likely to be elected. Perhaps one of the reasons for this is that women struggle to gain sufficient experience that time as an adviser can offer.

Political advisers are hard to observe

Political advisers are notoriously difficult to research because much of their work happens ‘behind the scenes’. Governments around the world aren’t too keen on making it easy to discover just how many publicly funded partisan staff they employ. These two factors make it hard to collect data on political advisers.

In our latest article for Political Studies we overcome this problem by using old telephone directories for Australian ministerial offices from the late 1970s through to 2010. These telephone books list all staff working in the office. The directories also include which Ministers advisers worked for, their job title and their gender honorific (eg. Ms vs. Mr).

To make the analysis more manageable, we collapsed work roles into five ranks using salary wage bands from the Australian Commonwealth government. Then we used sequence analysis to map career paths to investigate what work roles exist in ministerial offices, whether there are differences between the types of work men and women undertake, and how staffing roles have changed over the time.

What did we find?

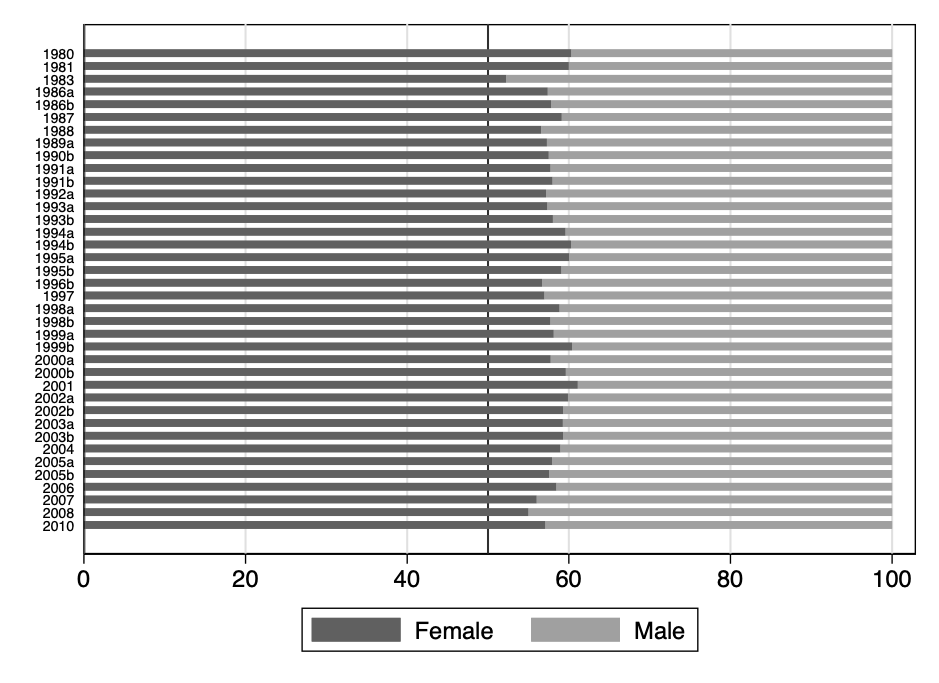

It may surprise you to know that since 1979, more than 50% of politically appointed staff in Australia are women (see Figure 1). This counterintuitive finding makes more sense when we account for the fact Australian ministerial offices are highly partisan. All workers, from the chief of staff to the receptionist, are partisan appointees rather than civil servants.

Figure 1: Proportion of male and female politically appointed staff in ministerial offices by ministerial staff directory

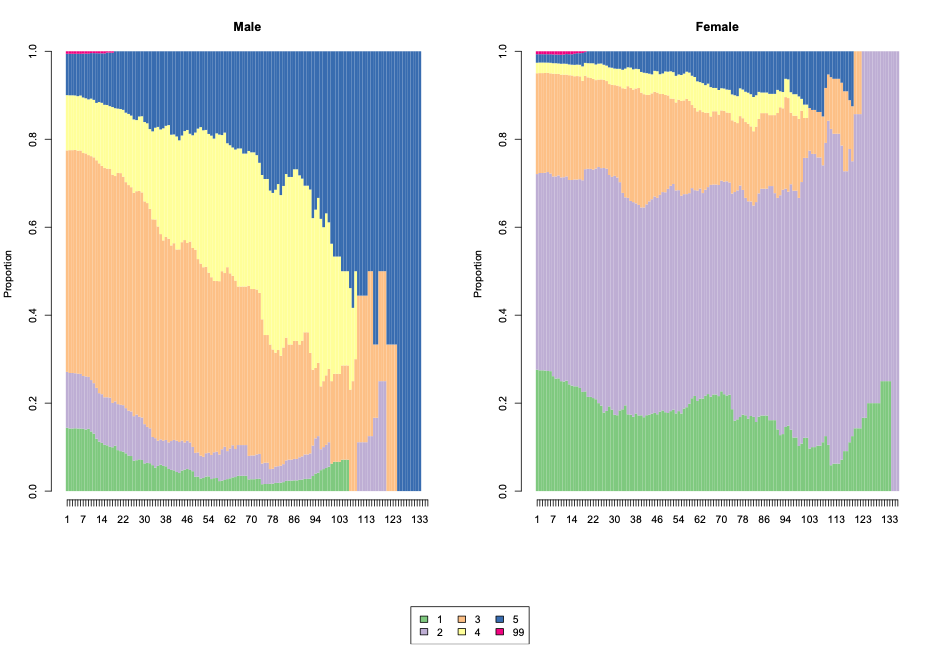

If we consider what work women undertake compared with men, the picture becomes clearer: women are far more likely to undertake lower status roles even though there is little difference in their average years of service (see Figure 2).

Figure 2: State distribution plot: politically appointed staff in ministerial offices, by sex

Note: Sequence analysis was originally developed to examine (and decode) DNA and protein sequences. In our case, instead of mapping protein sequences, we map career states according to 5 ranks (1 = lowest; 99 indicates we are uncertain of rank). Figure 2 presents a state distribution plot of ministerial staff’s transversal frequencies, which also illustrates the pattern contained within the sequence data. Each monthly column in the figure provides the frequency for each of the ranks occupied by politically appointed staff at that time period. Importantly, all staff in the data set appear at month 1, but as people exit staffing as a career, the overall number decreases. Typically, the last month represents only one person – that is the longest-serving staff member in the entire data set by calendar months.

What Figure 2 also shows us it that men and women appear to experience very different careers. Of the men working as politically appointed staff 50% will begin their careers at the ‘adviser’ or middle rank (rank 3) jobs. Over time, men are more likely to get promoted into senior-adviser (rank 4) or chief of staff (rank 5) type positions.

This is in sharp contrast to women. They dominate support-style jobs such as office administration or assistant advising in the rank 1 and rank 2 categories. Women are less numerous at the ‘adviser’ (rank 3) level. Although women finally reached 50% parity with men at this middle rank by 2010, women were less likely to be promoted to the most senior staffing levels compared with their male colleagues.

We can think of this another way: at the start of their careers only 4% of women begin at the most senior levels (ranks 4 or 5) and after five years this figure increases to 14%. By contrast, 22% of men begin their careers at the highest ranks (4 and 5) and increases to 51% at the five-year mark.

The result is that women begin and end their careers in lower status roles relative to men, are less proximate to the minister and are therefore less likely to have the discretion and resources to influence policy outcomes.

And what about pathways into parliament?

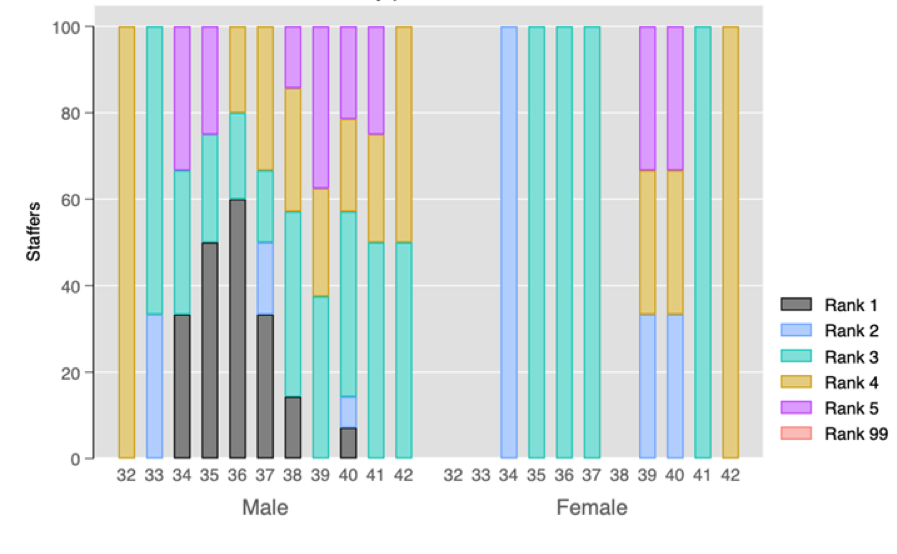

From our qualitative investigation, we found that women’s pathways that led them to working in ministerial offices – particularly in the early days – were often accidental. And the numbers of women entering parliament after political advising is considerably smaller. For men, there does appear to be a pathway into parliament either after gaining policy experience or experience in ‘over politics’, such as working as an electoral officer (see Figure 3). But this seems to be a male phenomenon.

Figure 3: Politically appointed staff in ministerial offices who went on to become elected representatives by parliament

Note: Data in Figure 3 only reflect government ministerial staff in each parliament (eg. the 32nd Australian parliament [Nov 1980–Dec 1982] and so on). This means staff working from 1979–1983 and 1996–2007 worked for Liberal and National Party governments. Staff working 1983–1996 and 2007–2010 were working for Labor governments.

For women, there do not appear to be any discernible patterns, reflecting that pathways into politics for women between 1980 and 2010 may have remained idiosyncratic and complex. We would add a further note of caution because the data above only include government staff, which may reflect important party differences in candidate selection.

While women have made significant gains in recent decades, they continue to occupy lower status and less proximate roles to the minister. Given that political appointees’ power derives from the minister, this distance is important.

In our paper we were able to demonstrate how to build a data set of a difficult to observe cohort, which will hopefully advance the comparative study of political appointees. We also demonstrated how work-roles differed across sex in ministerial offices. This has important implications not only for how we are represented and governed but also for our understanding of how political appointees’ careers fit into the overall lifecycle of elected elites.

This post represents the views of the authors and not those of Democratic Audit. A version of this article was first published on the PSA blog, and is republished with permission. It draws on the authors’ article “Who Does What Work in a Ministerial Office: Politically Appointed Staff and the Descriptive Representation of Women in Australian Political Offices, 1979–2010”, published in Political Studies.

About the authors

Marija Taflaga is a Lecturer at The Australian National University, Canberra.

Matthew Kerby is a Senior Lecturer at The Australian National University, Canberra.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.