How transparent and free from corruption is UK government?

For citizens to get involved in governing themselves and participating in politics, they must be able to find out easily what government agencies and other public bodies are doing. Citizens, NGOs and firms also need to be sure that laws and regulations are being applied impartially and without corruption. In an article from our book, The UK’s Changing Democracy: The 2018 Democratic Audit, Ben Worthy and the Democratic Audit team consider how well the UK government performs on transparency and openness, and how effectively anti-corruption policies operate in government and business.

Publications at an Anti-Corruption Summit, London. Picture: Cabinet Office via a (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0) licence

Publications at an Anti-Corruption Summit, London. Picture: Cabinet Office via a (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0) licence

What criteria for openness, transparency and freedom from corruption should government and public sector bodies meet in a liberal democracy?

- All government departments, agencies and public sector bodies should be open to public scrutiny through various easy-to-use means such as freedom of information legislation or open data, with clear channels and procedures for explaining policies and statistics in straightforward ways.

- Openness policies should extend fully to the private contractors and other providers (like NGOs and ‘third sector’ bodies) delivering services under contract to public authorities. Elsewhere in the private sector, registers detailing company ownership should be fully open, enforced and complied with across UK and associated territories.

- Extensive information on policies, change plans and options should be published pro-actively (voluntarily) by public bodies without the need for citizens to act or ask.

- Public bodies and politicians should promote an ‘open culture’ and create a series of deliberative and participative tools to allow citizens to take part in policy-making and key decisions.

- Anti-corruption policies should be well-developed, and rigorously and independently enforced. Citizens and enterprises should be confident that public administration and services will be delivered impartially, equitably and within the rule of law. ‘Whistleblowers’ should be protected and allegations of bribery or corrupt payments for services or lax regulation should be rigorously investigated.

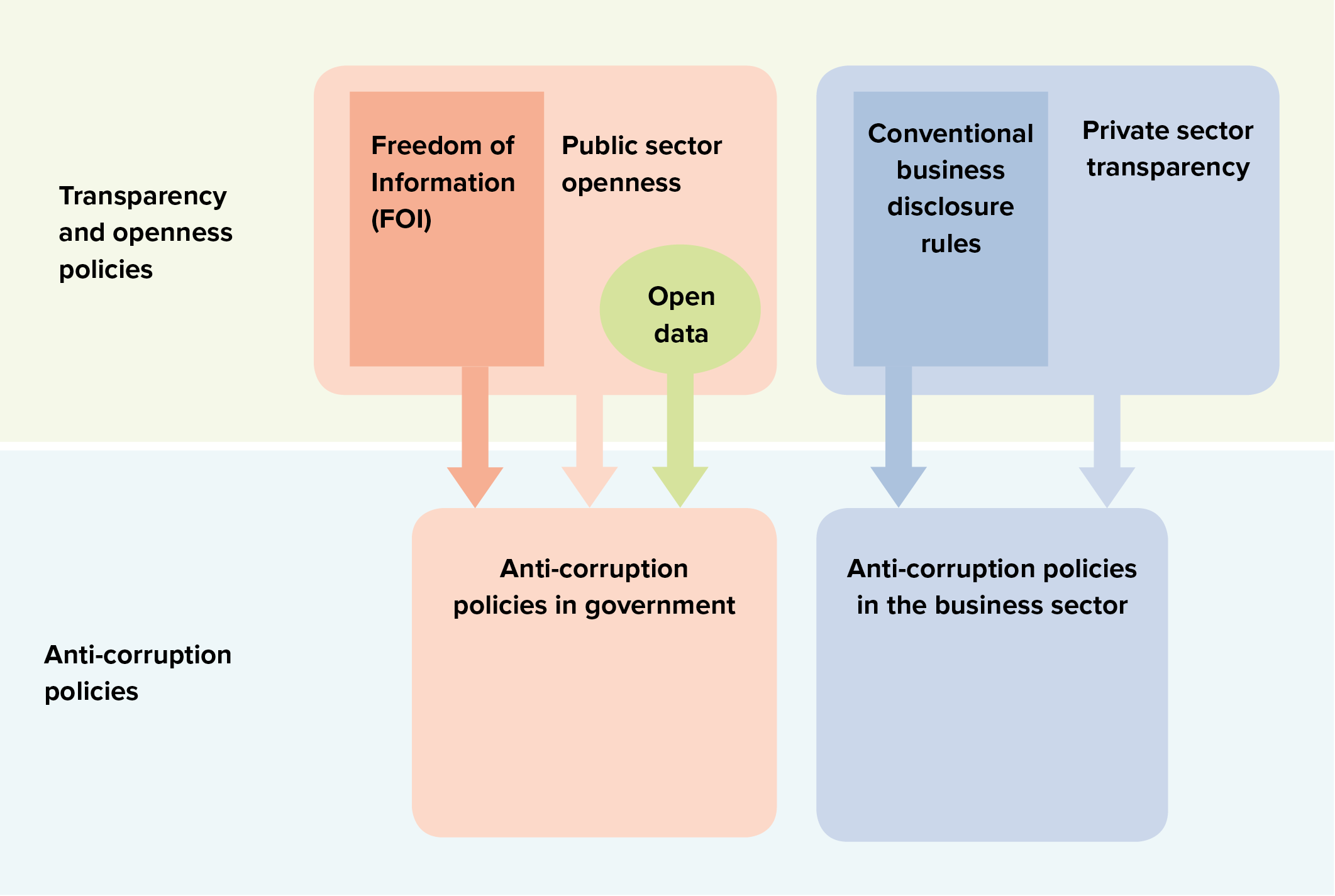

The openness and transparency of government and public institutions critically influences the health of democracy. Information flows between government and society are one of the key foundations on which public participation, the interest group process and an active civic culture are built. Figure 1 shows the main parts of this picture and how they interact.

Figure 1: The main types of transparency and anti-corruption policies

In the UK, a central and well-established element of government openness is provided by the Freedom of Information (FOI) Act, passed in 2000 and operational since 2005. It allows people to request information covering policies, implementation, spending and activities by over 100,000 public bodies, from government departments and agencies to local government, the NHS and police. It is overseen and regulated by an independent Information Commissioner.

The legal presumption is that all information in the government sector should be made available if requested. As with similar laws across the world, there are major exemptions for all intelligence and security issues (which are kept completely secret). Departments and agencies may also refuse to supply information that covers parts of the policy-making process, that is commercially sensitive, or in cases where an ‘excessive cost’ would be involved in assembling and providing what is asked for. Although it remains a ‘complex’ legal grey area, FOI can also be used to obtain information material ‘held by a private company “on behalf of” a public authority with which it has a contract’. Alongside FOI stand a host of sector-specific laws, governing everything from access to medical records to food labelling, as well as the General Data Protection Regulation that enables access to personal data.

A second wider set of policies that support ‘public sector openness’ includes the  production and publication of official statistics, legislation and regulations and public registers of the interests of politicians. These sit alongside older forms of publicity such as select committee meetings in Parliament or local government meetings that are open to the public.

production and publication of official statistics, legislation and regulations and public registers of the interests of politicians. These sit alongside older forms of publicity such as select committee meetings in Parliament or local government meetings that are open to the public.

Most recently, governments have sought to make data available in digital formats that can be easily re-used – known as open data. The government portal data.gov.uk now hosts more than 46,000 datasets covering a whole range of topics from departmental spending to health and safety statistics and ministerial gifts. At local government level, all councils publish online any spending over £500. Here the presumption is of ‘following the money’, so that if taxpayers have already paid to produce information, it should be made available free of charge – a radical revision of ‘new public management’-era policies of charging for bulk official information wherever possible. Data published by the government and other public bodies can also drive new platforms or apps. Some important innovators include MySociety’s TheyWorkForYou (on MPs’ activities) or Public Whip (with MPs’ voting records), while others such as Spend Network gather raw data on procurement.

Turning to the issues around private sector openness, most firms require commercial confidentiality in certain areas to protect their business. However, some degree of openness is also needed for markets and the business world to operate effectively, and to develop trust between businesses. This has long been achieved by conventional business disclosure requirements – such as registering company activities, annual reports and accounts with Companies House, listing directors of firms and providing information needed for publicly listed companies. Firms, executives, suppliers and customers all need to know something about the counterparts with whom they are dealing if markets are to work well. There are also transparency requirements where government meets business, with, for example, greater openness around contracts and coverage of business information held by public bodies or over ownership (see below).

However, the conventional business disclosure requirements are perfectly consistent with companies and wealthy people taking elaborate precautions to disguise the full scope or nature of their interests and activities behind ‘front’ companies and delegated personnel. In some cases, corporations have created complex (often byzantine) chains of ownership, where the true owner of a business, property or assets may not be easy to find. Accordingly, the newer private sector openness policies shown in Figure 1 seek additional information and clarity about who owns what, both for citizens, for those doing business with corporations, and for tax authorities. Some civil society movements and politicians also seek to force more information on into the public realm on corporations’ tax payments, which remain confidential (see below).

Transparency and anti-corruption policies are closely linked and overlap. Greater openness and publicity is seen as a vital means of preventing and exposing corrupt activity, as the arrows in Figure 1 indicate. Although the UK civil service, Whitehall and its agencies claim to be an open and ‘clean’ government, serious corruption problems have existed before – and they still recur across issues such as party funding, the self-regulation by politicians of their expenses, and the regulation of some kinds of business, from UK arms sales to overseas government customers to shell companies and UK tax havens.

Recent developments

All recent Prime Ministers have promised greater openness in government. However, Theresa May’s actions appear to have been less than meets the eye. She has often seemed to want to reject the style of the Cameron core executive that preceded her, and has been a secretive Prime Minister, unenthusiastic about any forms of transparency that could damage her government – especially after the loss of her majority in the Commons in 2017.

May inherited from David Cameron a series of ongoing anti-corruption reforms, as between 2010 and 2016 the UK sought to position itself as a global leader in anti-corruption at home and abroad. As Home Secretary, May had championed openness around ‘stop and search’ and police disciplinary openness – although, as critics pointed out, she was keener on her opponents’ transparency than on her own. May also led the UK’s work as part of the anti-money laundering action taken by the EU. In 2016 the government published a wide-ranging anti-corruption plan, and followed this up with a government-wide strategy in late 2017 (see below).

Some of these reforms appeared to lose momentum once Cameron resigned – perhaps as an unavoidable by-product of Brexit eating up parliamentary time, but perhaps also due to a lack of ministerial interest. The anti-corruption champion appointed by Cameron stepped down, and there was no replacement for more than six months. Other Cameron-era global initiatives on making business more transparent have become mired in controversy or were delayed (see below).

Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities, Threats (SWOT) analysis

| Current strengths | Current weaknesses |

|---|---|

| The general climate around openness and transparency agendas in the UK is positive, with cross-party support. A mixture of openness laws, executive instruments and technology have together created a flourishing openness ecosystem, with some strong forces pressuring for openness and preventing corruption. | The modern UK has only recently transitioned from a long-established administrative culture that used an all-encompassing notion of ‘official secrets’ – in which everything not explicitly published was treated as confidential. |

| The Labour governments of 1997–2010 put in place a series of important openness reforms. The unusual conservatism of the Cameron–Osborne Prime Minister and Chancellor team (2010–16), plus the presence of the Liberal Democrats in the coalitional government with the Conservatives (2010–15), produced a further period of UK government activism on transparency issues, especially around private sector openness, though enthusiasm for making government more open dwindled. | Since 2016 momentum has been slowing, and public sector openness policies have especially appeared to slow down if not stagnate. |

| Freedom of Information has important effects in increasing the openness of UK government and changing previously restrictive official cultures of secrecy. The 2005 legislation has frequently been lamented and queried by Whitehall mandarins and Westminster politicians, not least Tony Blair, who pushed through the law then regretted it. However, it has endured for 15 years and most attempts to increase restrictions have been fought off, while it has expanded in some areas. | There are already considerable exemptions under FOI legislation that allow government agencies to reject requests. There has been a notable decline in performance regarding FOI, with more requests refused over time and some reduction in the number of requests being made (see below). There are also recent examples of high-level political resistance in Scotland and Northern Ireland in 2018. |

| Public sector openness has increased in the digital age because large amounts of previously closed data and information can now be cheaply and effectively published online in forms that facilitate further analysis. ‘Open data’ policies have made an impact, especially in tandem with the growth of the Government Digital Service (GDS) during 2010–18. | There has been a slowing in open data publication, with some promised information lagging well behind formal timelines (see below). GDS has had its budget cut severely from 2019 on (see our Audit of the civil service). |

| Private sector openness policies designed to ensure that UK companies behave responsibly in developing countries have had some impact – for example, the UK has signed up to the OECD convention to curtail the bribery of foreign officials. Within the UK, greater transparency has been achieved in forcing public disclosure of who is the ‘ultimate beneficial owner’ of firms and properties, with new plans outlined for extending this to foreign companies, as well as with UK extractive companies working internationally. Greater business openness about gender pay inequalities have improved business social responsiveness. | Progress on several other anti-corruption fronts has been limited. Policies designed to force more disclosure about the use of natural resources from companies with large extractive industry holdings are ongoing but controversial. The Cameron government introduced a new ‘Google tax’ designed to raise more revenues from US and other MNCs paying little or no corporation tax in the UK, but by 2017 it raised only £270m, a fraction of the ‘missing’ taxes according to ‘tax shaming’ campaigners, and as it turns out not actually paid by Google or other similar tax-avoiding MNCs. |

| Anti-corruption policies in government are well developed. Britain regularly scores highly as a country free of corruption, usually ranking 8 to 10 in perceptions of corruption out of 176 states covered worldwide. Nonetheless, organised networks of open government and anti-corruption activists have pushed for further reforms. Under David Cameron, the UK was a founding member of the Open Government Partnership (OGP) in 2011. This involved a commitment to a UK government-wide anti-corruption plan and, later, an anti-corruption strategy. DfID have proved a high-profile champion. Devolved governments also have a series of openness initiatives in train. | Despite claims of being corruption free, problems persist. In Northern Ireland, a major scandal involving a Renewable Heat Incentive (RHI) scheme was uncovered in late 2017, with severe political consequences for the government. Yet the discovery of past long-run ‘cop-culture’ cover-ups (such as that over the Hillsborough football stadium disaster or undercover cops having relationships with surveillees), plus more recent evidence of official inaction on some child sex abuse and other malfeasance cases, has raised fears of a wider official malaise in UK public life. The issue of funding of political parties has continued to prove controversial and, in particular, the funding of the ‘Leave campaign’, as has MPs’ links to donations. The #MeToo campaign (following allegations of harassment in Hollywood) extended to the UK and led to new independent procedures, introduced in July 2018 (see below). |

| Anti-corruption policies in business are complex to introduce, since business law has to be carefully tuned so as not to deter investment nor hinder UK success in international trade. However, action has been taken to yield more information on UK companies’ beneficial ownership overseas. UK tax agency HMRC has also worked with Swiss authorities to identify potential British tax evaders following reduced banking secrecy there, and HMRC has also followed up on the ‘Paradise Papers’ leaks of apparent tax evasion structures used by wealthy people and companies in November 2017. The opening up of UK dependencies and overseas territories that are tax havens, begun under David Cameron, is ongoing. | There is a lack of government support and interest in promoting openness or anti-corruption in business. A number of key anti-corruption policies appeared to have slowed down or lost momentum. Major questions have been raised but left unanswered about whether bribes or commissions are paid on some very large overseas contracts, especially in the area of arms sales – where British Aerospace (BAe) is the world’s third largest armaments company. |

| There is a general push for secrecy around Brexit, while a lack of UK resources and perhaps declining powers of scrutiny outside EU law may increase the potential for domestic corruption. | |

| There are also obvious areas of weakness around the transparency of political parties’ funding and funding of campaigns, as shown with claims around ‘dark money’ and the Brexit referendum campaign. |

| Future opportunities | Future threats |

|---|---|

| The ongoing Whitehall commitments under the Open Government Partnership, plus experiments at devolved government level, offer opportunities for more transparency and anti-corruption activities. Local government is often a site of openness experiments and the new metro mayors may also offer an opportunity here. | Brexit will take time, energy and attention away from many other reforms. Leaving the EU may also have adverse effects on particular pieces of previously operating openness legislation, especially over environmental disclosures and information. |

| A range of potential sources of political corruption, such as over expenses, lobbying and funding of party and referendum campaigns, have not yet been fully addressed. |

Freedom of Information

The Freedom of Information (FOI) Act has been in place since 2005. It played a part in opening up the MPs’ expenses scandal in 2009 and a host of important stories. Behind the headlines, FOI is primarily a local tool, and around four in every five requests goes to local government: in 2012 an FOI request even led to the mass resignation of one village council. Although most requests are for micro-political or small issues, FOI has had some unexpected benefits, such as leading to an online postbox finder. And, by pressuring for the release of local restaurant hygiene inspection reports, it ushered in the ‘scores on the doors’ system of hygiene ratings.

The scope of the FOI law has also gradually expanded. Since 2012 it has covered exam bodies and databases, and in 2015 the strategic rail authority came under FOI, owing to a change in its accounting designation. Scotland’s separate FOI (Scotland) Act (FOISA) for devolved matters has also gradually extended to cover independent schools and certain leisure trusts.

The UK’s Third National Action Plan for the Open Government Partnership (OGP) committed to implementing the recommendations of a 2016 independent review commission, which included greater pro-active transparency over pay for public bodies and enhanced publication of FOI statistics. Changes were to be enshrined in a new code of practice issued under section 45 of the FOI Act. It was due in the summer of 2016 but was delayed, and was finally published in the summer of 2018.

There has also been pressure to strengthen FOI’s legal control over private contractors working for government – on which UK central government spends over £180bn a year. Section 5 of the Act allows governments to extend the law to cover companies within the scope of the Act itself, a power that the Commons’ Public Accounts Committee and others have previously urged should be implemented. However, successive governments have not extended FOI to private sector contractors, despite manifesto pledges and promises to do so. Since 2016, the Information Commissioner has championed the inclusion of private sector bodies directly under FOI, something that the independent review suggested and that MPs have continually pushed through a series of Private Members’ Bills.

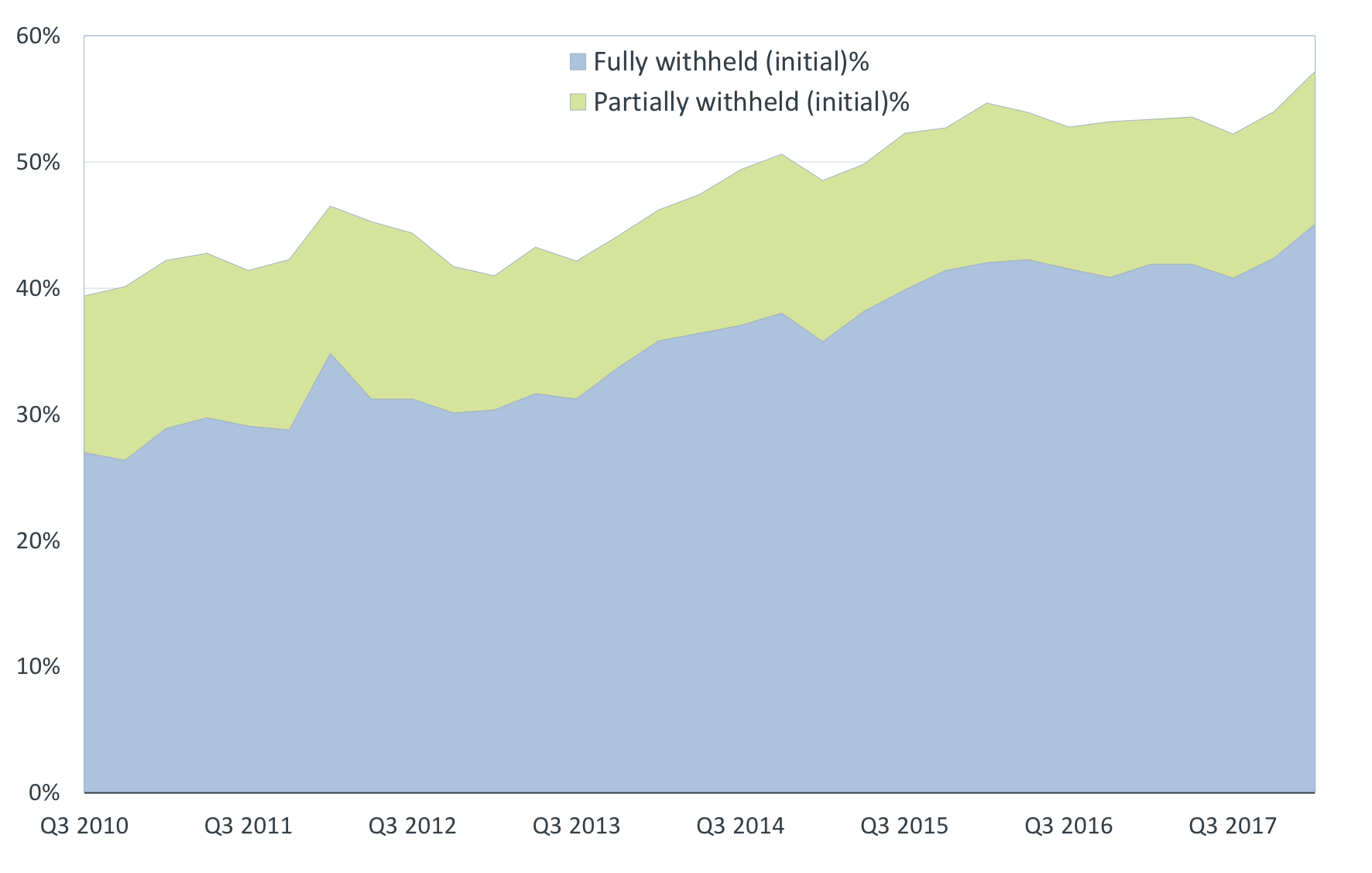

Recently evidence has accumulated of a slowdown in FOI responses across central government. The numbers of requests to central government per year fell by 6% from a high point of 51,000 in 2013 to 46,681 in 2017. One worrying assessment concluded that departments are ‘withholding more information in response to FOI requests’ and showed that ‘since 2010, departments have become less open in response to FOI requests’. While 39% of requests were ‘fully or partially withheld’ in 2010 a full 52% were ‘fully or partially withheld’ in 2017. This is probably a combination of austerity and a lack of staff but also dwindling enthusiasm and negative signals from above. There may also be a negative cycle at work whereby as more departments perform badly, so it becomes less likely that there will be any repercussions. Analysis by the BBC also pointed to a lack of action by the regulator.

Figure 2: The percentage of Freedom of Information requests where government departments refused a response, from 2010 (third quarter) to 2018 (second quarter)

Source: Institute for Government Whitehall Monitor, 2018, p.95, and updated data June 2018. Notes: IfG analysis of Cabinet Office and Ministry of Justice data; covers resolvable cases only.

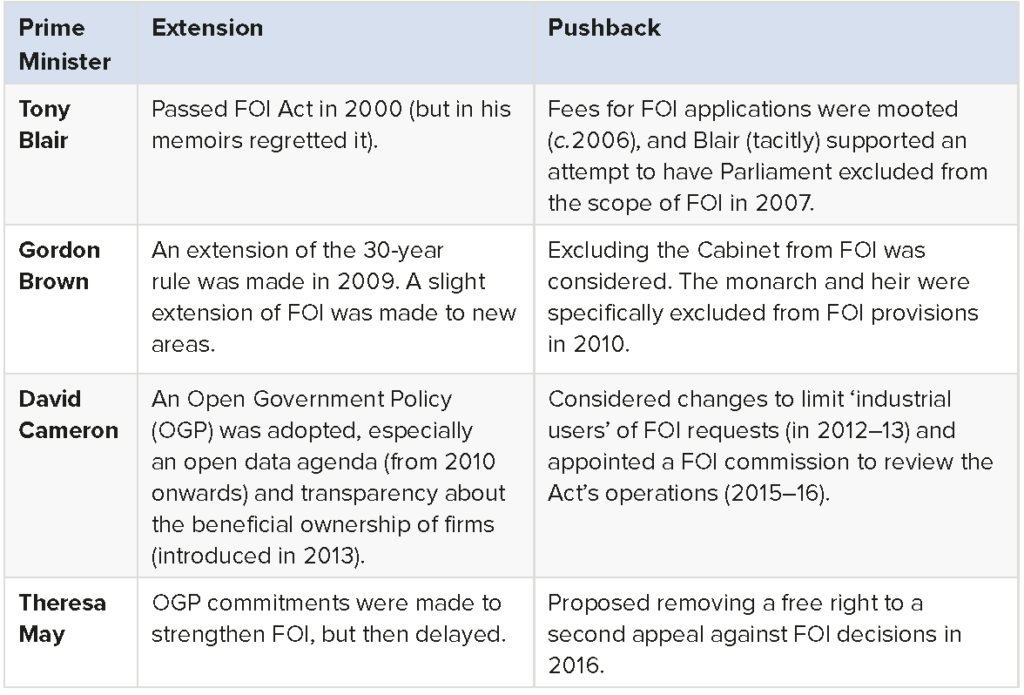

As well as dwindling enthusiasm and co-operation, since 2005 there have been a series of ‘behind the scenes’ attempts at ‘dismantling’ or chipping away at parts of the law, with roughly one proposal floated every 18 months to two years. They began under Tony Blair with a proposed introduction of fees or change to the cost limits in 2006, followed by an attempt via a Private Members’ Bill to remove Parliament from the FOI law in 2007. Under Gordon Brown in 2010 there was a proposal to remove from the scope of FOI the monarch and heir (Prince Charles). The Conservative–Liberal Democrat coalition then mooted a clampdown on ‘industrial users’ of FOIs (2012–13) and the Conservative government suggested extending the ability of departments to refuse information (2015). In 2016–17 the UK government proposed that fees should have to be paid for the second stage of FOI appeals (which had previously been free). However, a ruling on a related issue over access to justice from the Supreme Court in July 2017 put this policy in doubt. In June, the draft Patient Safety Bill also sought to make secret certain investigations in hospitals.

Figure 3 shows that most Prime Ministers have been somewhat ambivalent about the Act. In his autobiography, Tony Blair famously bemoaned passing the law:

‘The truth is that the FOI Act isn’t used, for the most part, by “the people”. It’s used by journalists. For political leaders, it’s like saying to someone who is hitting you over the head with a stick, “Hey, try this instead”, and handing them a mallet’ (2011, pp.516–517).

Though the evidence does not support this claim, it tells us much about how politicians see it. Just as Blair regretted his innovation, so Cameron described FOI as a ‘buggeration factor’ and claimed it was ‘furring up the arteries of government’.

Figure 3: UK Prime Ministers and policies on FOI, 2005–2017

Despite repeated claims by politicians and officials, there is in fact little evidence that FOI is harming records or efficiency. However, there appears to be growing resistance and avoidance at the top of government, strengthening in the course of 2017–18.

Despite repeated claims by politicians and officials, there is in fact little evidence that FOI is harming records or efficiency. However, there appears to be growing resistance and avoidance at the top of government, strengthening in the course of 2017–18.

Issues around FOI have been particularly controversial in Scotland, which has its own FOISA law covering Scottish matters. It differs slightly from the UK-wide law. In 2018, following complaints by Scottish journalists, a report by the Scottish Information Commissioner concluded that the government had sought to create a ‘two-tier’ system delaying journalists or politically sensitive requests. At the same time, Northern Ireland’s most senior civil servant, David Sterling, informed the inquiry into the Renewable Heat Incentive (RHI) scheme that records had not been kept of certain sensitive political meetings, as politicians wished for a ‘safe space where they could think the unthinkable and not necessarily have it all recorded’. Given the nervousness of both the DUP and Sinn Féin, officials had ‘got into the habit’ of not recording all meetings.

As well as a reaction against FOI, there were a series a series of attempts to limit openness or control information more generally. Perhaps most significantly, the UK government passed the Investigatory Powers Act in 2016, which gave a legal right to bulk data collection by intelligence agencies and, as one newspaper put it, ‘legalises a range of tools for snooping and hacking by the security services’. Although there were independent judicial checks built into the Act, there was considerable national and international concern at the potentially wide-ranging powers it gave intelligence agencies. In parallel, the Law Commission examined the possibility of strengthening the Official Secrets Act, which would, campaigners argued, make whistleblowing more difficult. This rapidly ran into media controversy for its flawed consultation processes and was put aside for further consideration until autumn 2018 (see Chapter 3.3).

Public sector openness and ‘open data’

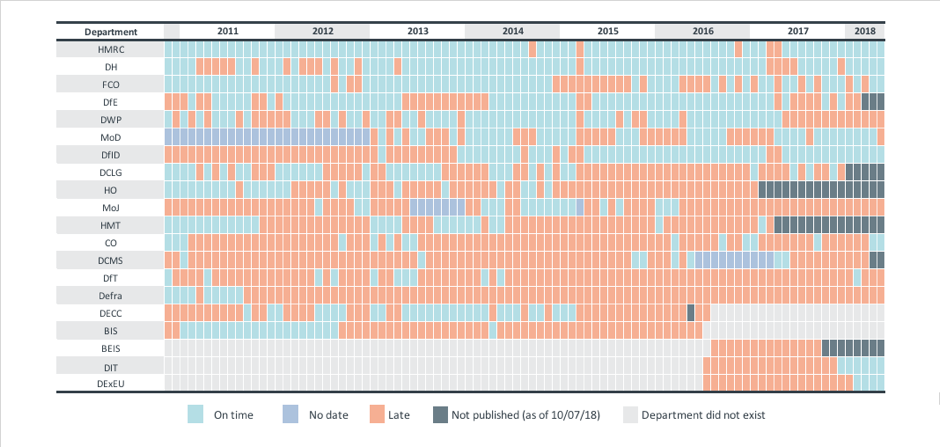

Successive governments have also pushed a series of ‘open data’ reforms, enshrined in variety of codes or released via data portals. Whitehall and local government has voluntarily published more of its data sets to allow private sector and civil society actors to analyse them, and potentially to develop new applications. Early in his premiership David Cameron promised that all Whitehall departments would publish every spending decision worth over £25,000. The move aimed to help small businesses so they could see where opportunities for tendering might exist, and to give citizens oversight of what was being contracted on their behalf. At the same time local government in England was asked to publish all spending decisions over £500. Figure 4 shows that while many central departments complied, publication remains patchy and was often late, perhaps falling off also in recent years.

Figure 4: How well different Whitehall departments have met the UK government’s pledge to publish monthly details of all spending over £25,000

Source: Institute for Government, Whitehall Monitor 2018, and updated data up to July 2018

One key focus for open data is procurement. Public sector contracts in the UK are currently worth around £93bn per year according to the Information Commissioner’s Office (ICO). Successive governments have innovated with open contracts, publishing central and local government contracts according to the Open Contracting Standard. It has also developed (and subsequently re-developed) the one-stop Contracts Finder website, a searchable database of public contracts.

A series of parliamentary select committees and MPs have kept up the pressure for more openness about procurement, and have identified ‘significant gaps’ in contractual data. The Institute for Government pointed out that, despite Contract Finder, ‘there is no centrally collected data outlining the scope, cost and quality of contracted public services across government… it’s currently impossible to find out precisely how well contractors delivering government services perform’. In the wake of the collapse of the large government contractor Carillion, one select committee called for greater published information about contracts and how procurement arrangements have worked or met its targets, while also suggesting coverage by FOI. Campaigners have also called for greater openness of local government procurement: as one pointed out ‘the day after Carillion’s collapse it was only possible to locate less than 30 of the 400+ government contracts with Carillion through the national Contracts Finder dataset’.

Elsewhere across government, the Department for International Development (DfID) have used open data as part of their and anti-corruption strategy, creating a development tracker that allows users to see development spending around the world. In 2018 the government also announced the publication of a tranche of OS master map data covering a range of property boundaries and other crucial ‘building block’ data of great use to developers.

Other open data commitments have fared less well. A commitment to publishing local election results data according to a common standard proved slow-moving because of the need to carry with it local authorities. And an initiative to push for publication of election candidate diversity data under section 106 of the Equalities Act, which would enable us to see any gender gap in those running for office, has been delayed repeatedly.

The OGP national action plan assigned a lot of weight to extending the UK’s single official website, gov.uk, built by the Government Digital Service (GDS), which also consulted data users in shaping the future of open data, sought to identify core data assets and published information on grants data. There are concerns that GDS is showing signs of lacking both overall vision and that there was ‘an absence of really deep thinking’. This links to criticism of the government’s lack of an overall strategy or joined-up thinking across government and from 2018 the GDS budget was cut back (see Chapter 5.3 on the civil service). In April 2018, digital policy and control of GDS was transferred to the Department for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport (a department with a poor digital record in areas like libraries policies). DCNS is also not a core department (unlike the Cabinet Office) and there was further concern that the move would lead to a lessening of priority, especially with rapid ministerial turnover.

There is also considerable movement on openness at the devolved level. Both the Welsh and Northern Irish governments (following proposals ongoing before the Assembly’s collapse) are also making reforms to their own data portals, and the Welsh government’s Well Being Act of 2015 also mandates publication of information and targets. The Scottish government published a separate openness plan with commitments to more transparent budgets and greater local community involvement.

Anti-corruption policies in the government sector

The UK is rated highly by most international indexes on anti-corruption policies in government. For instance, the leading NGO, Transparency International, assigns it a score of 82 (out of a maximum 100 points) and ranks it as the eighth least corrupt country globally. The 2016 OGP national plan included pledges to ‘incubate an Anti-Corruption Innovation Hub to connect social innovators, technology experts and data scientists with law enforcement, business and civil society to collaborate on innovative approaches to anti-corruption’. It also pledged to ‘develop, in consultation with civil society, and publish a new anti-corruption strategy ensuring accountability to Parliament on progress of implementation’. A strategy document to 2022 was published in 2017 but contained few specific new actions. The Labour opposition also applied pressure on what it claimed was the government’s failure to push ahead with its anti-corruption agenda.

However, highly consequential corruption issues have none the less occurred, notably in 2017–18 in Northern Ireland when the Renewable Heat Incentive (RHI) scheme, known as the ‘cash for ash’ scandal, broke. Begun in 2012, this policy initiative aimed to create an incentive for businesses in Northern Ireland to switch from gas and oil to wood pellets. However, owing to errors in the scheme, businesses could profit from it (for example, by farmers just burning wood pellets pointlessly to attract the subsidy). The bill for the policy reached £500m and, after officials expressed concern that it was being used fraudulently, the scheme was rolled up in 2016. Although whistleblowers sought to expose the problems as far back as 2014, it was not until further claims were investigated by Stormont’s Public Accounts Committee that the scandal broke. The inquiry remains ongoing with controversial claims over access, undisclosed contacts and officials failing to record key meetings.

A motion of no confidence in Arlene Foster, the minister who initially set up the scheme, but who was by the time the scandal was exposed, the leader of the Democratic Unionist Party (DUP), the largest party in the Executive, failed due to Stormont’s cross-community procedures. Foster called instead for a full public inquiry, which has not materialised. The scandal contributed a great deal to the resignation of Sinn Féin’s Martin McGuiness and the collapse of the Northern Ireland Assembly and Executive in January 2017. In June 2017 Foster and the DUP offered Theresa May key backing to stay in office at Westminster on a confidence and supply basis, in return for a ‘bung’ to boost spending in Northern Ireland by a reputed £1.8bn. The Assembly remains suspended.

Many civil society critics argue that corruption is deeply rooted in the link between money and UK politics, in particular areas such as expenses and funding of parties and campaigns.

There has been controversy over use of expenses in the House of Lords and the influence of donations and dark money in the Vote Leave campaign. In November 2017 the electoral commission announced an investigation into donations by Arron Banks to the Leave campaign. In 2018 it emerged that he met with the Russian ambassador and other officials 11 times in the run-up to the referendum, when his potential involvement in businesses in Russia was also discussed. In July 2018, the Electoral Commission concluded that Vote Leave had broken the law, and fined them £61,000 and passed the information to the police. The Select Committee for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport continued detailed scrutiny, despite refusals to appear by key witnesses including Dominic Cummings, campaign director of Vote Leave. Research by Peter Geoghegan and others has also raised a series of unanswered questions over other Leave donors, including a substantial contribution to the campaign routed via the DUP in Northern Ireland. The government legislated to open Northern Ireland political donations henceforth, but conveniently limited transparency to all donations made after July 2017.

In the last years of the Major government (1992–97) allegations of Tory ‘sleaze’ became influential, linking together both corruption issues and allegations of sexual misconduct. This media focus has not returned, but in October 2017 sexual harassment revelations and allegations about the Hollywood producer Harvey Weinstein triggered internal publicity and the #MeToo campaign which spread to the UK. A series of allegations of harassment by MPs and ministers were made, with an anonymous list circulated of alleged abusers and scandals. As Rainbow Murray pointed out, the scandal was ‘not just about sex, it’s about power’ and the abuse is rooted in the silence and secrecy that surrounds the operation of the whips and party loyalty.

Within a year, two Cabinet ministers (including the First Secretary of State Damian Green) and two whips resigned from the government over alleged sexual misconduct issues. MPs from across parties have faced allegations, with the whip withdrawn from several Conservative and Labour MPs. The Conservative Party instituted a new code of conduct and disciplinary procedures while Labour set up an independent inquiry. The same strand of scandal also spread to the Liberal Democrats and to the Scottish Parliament. Elsewhere in Parliament, a series of high-profile figures were accused of bullying, including the Speaker John Bercow and Labour MP Keith Vaz.

In the summer of 2018, further scandal hit parliament with Transparency International opening up issues around hospitality from corrupt regimes including Azerbaijan, Russia and Bahrain. In the same month, DUP MP Ian Paisley Jr was suspended from Parliament over undeclared lavishly funded holidays and paid advocacy, with the possibility raised that the UK’s 2015 recall law could be used to trigger a by-election (although the constituency petition required ultimately did not receive enough signatures for this to take place).

At local government level the abolition of the audit commission, the decline of the local press and the relatively weak power of Overview and Scrutiny Committees inside local authorities generated fears that municipal corruption could become more likely or, at least, less detectable. Critics hope that new citizen based innovations such as the Bureau of Investigative journalism’s ‘bureau local’ and people’s audit can help maintain some scrutiny. England’s new elected metro mayors do not answer to an assembly (unlike the London mayor), but instead face only scrutiny by councillors from local authorities from across the metro area under arrangements that citizens will find hard to follow.

Transparency in business

We noted above that legally mandated disclosure and registration of conventional business information is important for market actors to know whom they are dealing with when contracting for the supply of goods and services, accepting payments or extending credit. The UK system is run from Companies House and fulfils these needs reasonably well, so that basic information on companies and directors can be found. In addition, of course, this information is critically important for the efficacy of both government regulation and tax collection.

However, this system contains enough loopholes for companies to stay disguised behind ‘shell’ and ‘nominee’ companies and interlocking holdings by wealthy people and corporations, while also sheltering various (legal) tax havens in some form under the UK’s jurisdiction. (In theory, tax authorities should be able to get further than other actors, but in practice their enquiries are also often frustrated.)

At first sight, these might seem to be issues that Conservative ministers would not want to pursue. The Tory Party is pro-business, deplores the regulatory burden on companies, and so is generally against increasing it. It is also not keen on imposing barriers to innovations. Yet in the coalition period Cameron, Clegg and Osborne publicly took a dim view of such loopholes leading to tax losses. With the austerity pressures acute from 2010 to 2016, the potential missing revenues from non-disclosure of ownership and legal tax avoidance were matters of concern to ministers, as was the symbolism of closing (or critics would say, to be seen trying to close) ‘tax haven loopholes’ in UK overseas territories and dependencies at a time of deep cuts. Ministers could make political capital from the symbolism of targeting ‘abuse’ of the system and the link to money laundering and crime. The politics of this, sometimes labelled the ‘Nixon goes to China’ effect, meant that such action would be easier for a Conservative politician to bring in than for a Labour politician.

David Cameron promised an open register of ‘beneficial owners’ of UK businesses in 2013, under which all companies would have to identify their real owner or ‘people with significant control’ . Since June 2016, all companies have been mandated to keep such a register and submit the data to Companies House. As of 2018 more than 3.6 million companies had registered data.

Global Witness argued that the data had illuminated a huge area of business activity, attracting large public interest and setting a new agenda for more reform, especially over the opening up of previously opaque areas such as Scottish Limited Partnerships. As a measure of the success, the Companies House data had more than two billion hits since June 2015, compared with six million per year before. However, analysis of the data also revealed significant issues with data quality and compliance, with ‘thousands of companies…filing highly suspicious entries or not complying with the rules’, including ‘a statement that the company has no [person with significant control], disclosing an ineligible foreign company as the beneficial owner, using nominees or creating circular ownership structures’.

In 2016, following consultation and an open government partnership commitment, the UK promised to extend beneficial ownership specifically to ‘establish a public register of company beneficial ownership information for foreign companies who already own or buy property in the UK, or who bid on UK central government contracts’. The government aims to have the new extended register operational by 2021, though others have called for it to be sooner.

A related issue that spans across both public and private sector openness concerns the (still completely confidential) tax arrangements of large companies in the UK, which often involve ‘booked activity shifting’ to the most tax-efficient locations in a multi-national corporation’s (MNC) operations. From 2008 onwards a range of social movements sought to ‘shame’ MNCs (especially American ones) into paying more corporation tax, which is extensively evaded by elaborate ownership and domicile arrangements.

Tory ministers began to be concerned that, in addition to the Exchequer losing tax revenues, there were complaints from medium and small British businesses that they were facing unfair competition from the likes of Amazon because they paid corporation tax and the multi-nationals did not. To head off these criticisms without tackling the much larger underlying legal problems, Osborne created a special tax of 25% levied on large company profits that were diverted via ‘contrived arrangements’ to tax havens. Some giant companies (like Amazon) announced that they would stop booking profits via Luxembourg to avoid paying the tax, but the anticipated revenue gain to the Exchequer proved to be relatively small.

The push for private sector openness also led to the UK government taking part in the international Extractives Industries Transparency Initiative and publishing data on UK extractives companies. This means that ‘more than 90 oil, gas and mining companies incorporated in the United Kingdom or listed on the London Stock Exchange (LSE) now publish their reports on payments to governments each year under UK law’. In parallel, the government has developed greater openness in this area through a series of EU regulations. A government review in the summer of 2018 concluded that ‘the law had been a success in bringing greater transparency to the sector with no unnecessary costs to business, and found no indication that it harms companies’ commercial interests’. A working group continued meeting on this into 2018, but some changes have become mired in controversy between government and civil society.

One of the most high-profile recent controversies over business disclosure rules occurred over companies publishing data on gender pay gaps. A legal requirement to publish gender pay data was first contained in section 78 of Labour’s Equalities Act of 2010, but was then not implemented by the Conservative–Liberal Democrat coalition. The Cameron government then committed in 2015 to mandate all companies over 250 employees to publish data, with the promise that this would ‘put the UK at the forefront of gender pay transparency’. The May government continued (and took credit for) the bipartisan policy so that from April 2018 companies have had to produce the data. By July 2018 some 10,660 business had reported and the gov.uk website includes a searchable database of all reports, so employees can find out how their firm is performing.

The issue received high levels of media attention and kickstarted a Twitter campaign and grassroots initiatives encouraging female employees to speak up in their organisations. However, a survey for the Young Women’s Trust found that many businesses were unconvinced: ‘44% of those making hiring decisions say the measure introduced last April will not lead to any change in pay levels’. In 2016, the Women and Equalities Select Committee concluded that pay publication focuses attention on the issue, but is not in itself a solution: ‘It will be a useful stimulus to action but it is not a silver bullet’. It recommended that ‘the government should produce a strategy for ensuring employers use gender pay-gap reporting’.

Anti-corruption policies and business

Aided by the shifts towards more business openness, at the global level the UK under Cameron also sought to become a champion of anti-corruption in business, pushing national and international anti-corruption commitments. Reforms included extending new beneficial ownership regulations and, as a continuation of the coalition government’s efforts, some clamping down on tax havens and money laundering.

The initiative on beneficial ownership (above) partly reflected a desire by ministers to meet acute concerns expressed domestically and internationally that corrupt or ‘dirty money’ was flooding into the UK, with the property market in London being especially used to ‘launder’ large amounts of cash. Investigations into anonymous foreign property ownership in London found that of ‘14 new landmark London developments… four in 10 have been sold to investors from high corruption risk countries or those hiding behind anonymous companies’. There was further analysis of home ownership in the elite areas of Kensington and Chelsea borough in the wake of the Grenfell Tower fire disaster.

David Cameron pledged in 2016 to open up information from the (many) tax havens numbered amongst the UK’s dependencies and overseas territories by adopting public registers of beneficial ownership. Under Cameron, these were only partially successful, resulting in data-sharing agreements and promises to create (non-public) registers, and further undermined by revelations of Cameron’s own tax affairs.

Corporate corruption and issues of tax avoidance continued to dominated the headlines towards the end of 2017 with the leak of the so-called ‘Paradise Papers’, which comprised 13.4 million documents from the Appleby legal firm based in Panama and detailing the offshore arrangements of a host of UK wealthy people and companies. Revelations included the offshore investments of the Queen, linked to a company accused of exploiting the poor, and the secret tax and company arrangements of key Conservative donor Lord Ashcroft, who had committed to paying UK tax in order to sit in the House of Lords. When Transparency International examined Scottish Limited Partnerships, it described them as the UK’s ‘homegrown secrecy vehicle’, with more being set up in one year than in the whole of the last century.

Theresa May had committed to continuing Cameron’s agenda of clamping down on tax avoidance, but she and the Chancellor Philip Hammond refused to promise a full register of off-shore trusts following the ‘Paradise Papers’ leak. In May 2018, a cross-party group of MPs pressured the government to open up beneficial ownership registers to British overseas territories such as the British Virgin Islands and the Cayman Islands. The government agreed to do so but has since met resistance and even calls for ‘constitutional separation’ from some of the territories.

One area where the May administration has pushed a number of ‘signature’ openness reforms has been for greater transparency over executive pay. In mid-2017 the BBC was forced to make changes and publish the pay levels of its senior figures and stars paid over £150,000. These details generated a heated controversy over the stars’ remuneration and the organisation’s striking gender pay gap. However, in August 2017 the government watered down its election promises to open up business executive pay more generally.

Elsewhere in the UK, there has been new anti-corruption policy innovations. In June 2017, the Welsh government launched a new Code of Conduct for ethical employment in supply chains designed to prevent modern slavery and blacklisting of workers. The new Code is applicable to all its suppliers and the government hopes it will spread across the Welsh economy.

Brexit

Transparency and anti-corruption issues have featured heavily in the Brexit process. In 2016 the government appeared committed to a closed process with, as May put it, no ‘running commentary’. The UK government sought to use the powers of the royal prerogative to shield the negotiations (and to cover up divisions with government). However, a combination of leaks, rulings from the courts and pressure from Parliament has led, so far, to more openness than the government intended. This has included a White Paper, two Prime Ministerial speeches and a series of appearances in front of select committees. Although the government has been slow to publish position papers compared with the EU, these began emerging late on.

Freedom of Information provisions played a role with requests exposing turnover of officials at the new DExEU and the lack of preparation in the new Department for International Trade. Requests were used to attempt to access legal advice allegedly held by the government on whether Article 50 can be revoked. FOI and parliamentary questions and motions, including arcane procedures employed by the Labour opposition, were used to attempt to force the government to publish 50 papers on the effects of Brexit. In a single day in November, six select committees were examining various aspects of Brexit. In 2018, FOI was also used by Sky News to examine local authority Brexit contingency plans, finding that few could identify any benefits, and were looking into contingency planning for unrest or traffic chaos.

However, as the UK seeks new trade deals across the world, questions hang over the future of its anti-corruption reforms. The OECD warned that a combination of distraction and pressure to water down bribery laws may undermine the UK’s anti-corruption policy. As one expert argued: ‘With Brexit, and the need to hunt out new business in developing markets, a process of benign neglect may set in.’ It may be that ‘there is the danger of (more or less deliberate) neglect of the UK’s previously high profile anti-corruption thinking’.

Conclusions

Attitudes inside the UK’s government and public services towards transparency and openness have changed a great deal since 2005 and the advent of FOI. The changes made have attracted support from across the political spectrum, so that reforms have been cumulative and (so far) un-reversed. Yet the risks of openness being again eroded, or of matters that have become transparent closing up again, remain substantial. And, despite British politicians’ evident conviction that the UK’s experience holds lessons for the world, some serious gaps in anti-corruption policies remain.

This is an extract from our book, The UK’s Changing Democracy: The 2018 Democratic Audit, published by LSE Press. You can download the complete book here, and the individual chapter.

About the author

Ben Worthy is Lecturer in Politics at Birkbeck College, London and blogs about transparency and open data issues at https://opendatastudy.wordpress.com/.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

[…] Source: How transparent and free from corruption is UK government? : Democratic Audit […]