How the SNP’s post-referendum membership has changed the party – and what has stayed the same

As the SNP meets in Aberdeen for its party conference, James Mitchell looks at the impact of the 2014 post-referendum surge in membership on the party’s organisation and finances, and how this precipitated the proposed changes to the party’s constitution.

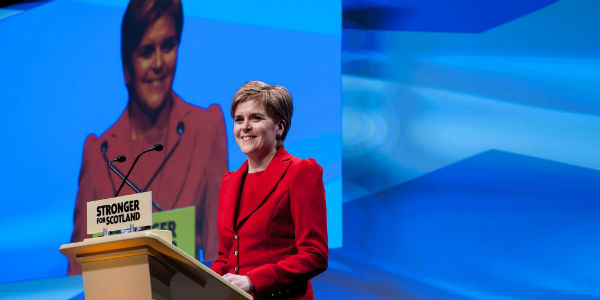

Picture: The SNP, via a (CC BY-NC 2.0) licence

Picture: The SNP, via a (CC BY-NC 2.0) licence

The SNP will consider changes to its constitution when it meets for its conference this weekend (8 and 9 June) in Aberdeen. This is the culmination of a debate on the party’s internal structures that was provoked by the massive influx of new members after the 2014 independence referendum.

While Angus Robertson, former Westminster SNP Group leader, won the depute (deputy) leadership contest in 2016, his parliamentary colleague Tommy Sheppard stood against him on a platform that included party organisational reform, ensuring it was on the SNP’s agenda. Since then, the SNP has deliberated and the leadership has come up with a set of proposed reforms. The changes focus on creating a regional structure that is currently absent in the party’s organisation. Amendments to these leadership proposals come from Tommy Sheppard and a number of Edinburgh branches, and these would potentially create alternative sources of power within the party. These amendments would give the new regional structures more teeth, with elected conveners and other elected office-bearers chosen by members in each region. For example, one amendment proposes to have ‘Regional Executive Committees’ rather than the leadership’s proposed ‘Regional Steering Committees’.

The SNP leadership has retained a tight grip on the party for many years, allowing it to move from the amateur-activist party of old to the more professional party it has become. Electoral success has helped the leadership keep control of a membership content with where the leadership has taken them. The party delegates may feel relaxed enough to deconcentrate power and encourage alternative voices and opinions, even if the party’s opponents and a largely hostile media will pounce on anything that can be presented as a ‘split’. But there will also remain within the party a belief in the need for tight control in the run up to another independence referendum or election.

Many of the new members attended local branch meetings in the immediate aftermath of the referendum and run-up to the 2015 election. In many cases new meeting rooms had to be found to accommodate this influx. Some branches saw new members replacing older members to hold local party offices. The membership surge was evident at party conferences, with many speakers introduced as ‘first-time speaker’. The numbers of those contributing to debates enhanced the impression of a party that was being refreshed and undergoing significant change (though there are few old-style SNP debates as the party has followed other parties in treating its conferences as public relations exercises).

However, behind the appearance of change lies considerable continuity. The vast new membership is largely inactive, and the growth in membership has not resulted in a similarly proportionate increase in activists. In the past, the proportion of active SNP members was higher than in other parties. The mass membership makes the SNP stand out but the proportion who are active is now in line with other parties. What proportion of these members might become active in the event of a second independence referendum is unknown.

One important aspect of the growth in membership has been as a substantial new source of party income. The days when a branch membership secretary would have to pay an annual visit to members to renew their membership are over. Automatic payment from a bank account provides greater financial security to the party. It now takes an effort to leave a party, whereas considerable effort was involved in renewing a branch membership in the past. This financial transformation has allowed the party to prepare for the long campaign to any independence referendum in a way that was not possible before 2014. The substantial Sustainable Growth Commission report published in May involved considerable independent research and analysis that the party would have been unable to pay for in the past.

Interviews with senior SNP members from across Scotland show that the initial burst of activity in the immediate post-referendum period has subsided. Some branch meetings have reverted to form (and size), though many have been refreshed and have larger turnouts than pre-referendum. One of the challenges debated inside the SNP, mainly within individual branches, is how to make meetings more interesting for new members, with some branches trying to reduce the length of time spent on the everyday house-keeping matters and allow more time for ‘politics’ – that is, discussing policy and strategy. These matters will not be directly debated at the Aberdeen conference but the hope is that regional conferences will allow branches to share experiences and learn from each other.

There has been much speculation on the nature of the new members and in particular their ideological predispositions. The evidence from a survey of members and the results of internal elections suggest that the massive influx of members has had very little impact on the party’s ideological centre of gravity. The SNP remains broadly moderate left of centre. This suggests that the result of the depute leadership contest (taking place since Angus Robertson stepped down following the loss of his Westminster seat) should result in victory for Cabinet Secretary Keith Brown. The degree of harmony inside the SNP has meant that the contest has, once more, been a polite and rather dull affair. The key figure may not be the share of the vote won by each candidate but the proportion of members who bother to vote. The nature of the depute leadership campaign, degree of party unity and nature of the new large membership will likely lead to most members not bothering to vote at all.

SNP conferences of old witnessed some heated debates, even the odd walkout by members who went on to hold senior office. Aberdeen is likely to be a rather dull affair by comparison, but that is testimony to the party being at ease with itself and confident in its leadership.

This article gives the views of the author, and not those of Democratic Audit.

About the author

James Mitchell holds chair in public policy, Edinburgh University. His books include Hamilton 1967, Luath Press, 2017; with Rob Johns, Takeover: explaining the extraordinary rise of the Scottish National Party, London, Biteback Publishing, 2016, and The Scottish Question, Oxford University Press, 2014. He co-directs the SNP/Scottish Green Party ESRC study ‘Recruited by referendum’, RG13385-10. He tweets @ProfJMitchell.

James Mitchell holds chair in public policy, Edinburgh University. His books include Hamilton 1967, Luath Press, 2017; with Rob Johns, Takeover: explaining the extraordinary rise of the Scottish National Party, London, Biteback Publishing, 2016, and The Scottish Question, Oxford University Press, 2014. He co-directs the SNP/Scottish Green Party ESRC study ‘Recruited by referendum’, RG13385-10. He tweets @ProfJMitchell.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.