Just how much do voters trust Scottish parties’ social media posts?

Do people believe the ‘facts’ circulated on social media by political parties? Graeme Baxter, Rita Marcella and Agnieszka Walicka showed Scottish voters five posts from different parties and asked them to rate their reliability. The Scottish Greens’ post was viewed as the most trustworthy, with participants identifying a wide gap between their experience of local politicians and the national debate.

Image: Composite via Emojipedia

Back in 2014, during a study of voters’ online information behaviour conducted in the build-up to the Scottish independence referendum, we found citizens to be generally sceptical about the reliability of information presented online as ‘the facts’ or ‘the truth’ by Better Together, Yes Scotland, and the main Scottish political parties. This led us to conduct another study in 2017, which focused specifically on the public’s perceptions of online political ‘facts’.

This study consisted of two key elements: an online survey (538 responses) which gathered opinion on the reliability of ‘facts and figures’ contained within five social media posts made by the main Scottish parties; and 23 extended, face-to-face interviews with citizens in Aberdeenshire, North East Scotland, where they were asked to consider information presented as ‘facts’ on the Scottish parties’ websites.

The five social media posts appearing in our online survey are presented below. Figure 1, posted by the SNP, talked about the ‘positive initial destinations’ of school leavers:

Figure 2, from the Scottish Conservatives, attacked the SNP Government’s record on college places:

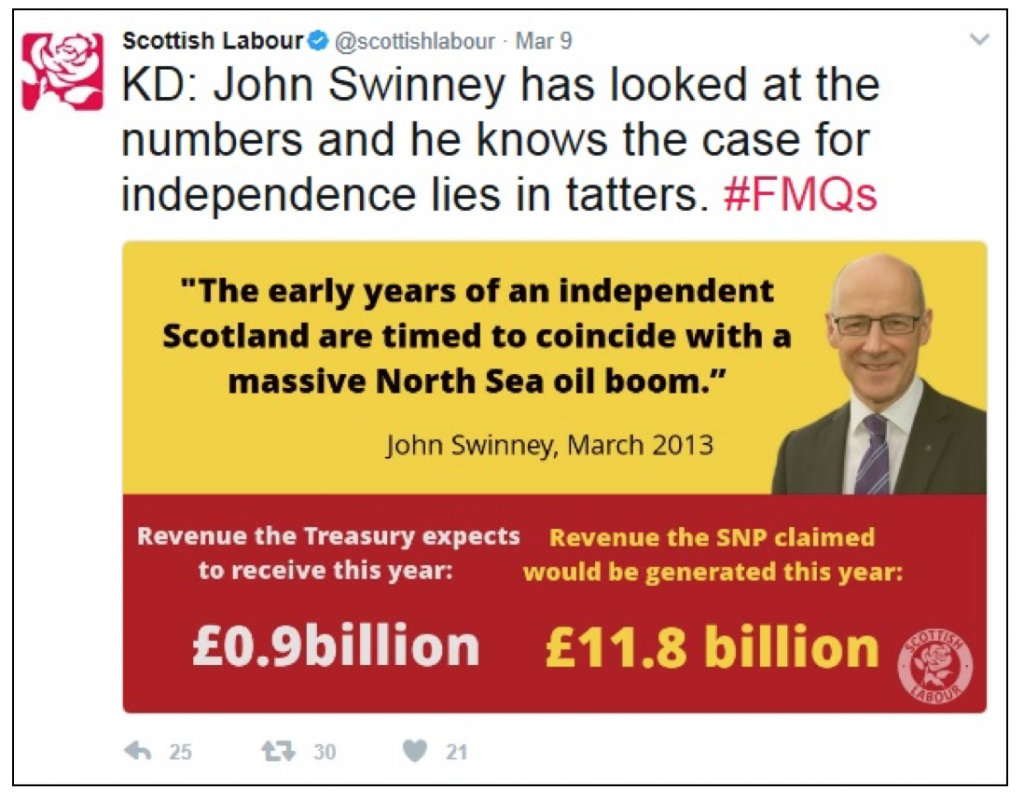

Figure 3, from Scottish Labour, questioned the SNP’s pre-referendum oil revenue forecasts:

Figure 4 saw the Scottish Greens highlight childcare costs:

Figure 5, from the Scottish Lib Dems, also attacked the SNP Government’s 10-year record on education.

These five images were chosen deliberately by the researchers, as none gave any indication of the source of the ‘facts and figures’ presented. This, it was hoped, would prompt our respondents to give some real thought as to the accuracy and trustworthiness of the information. (It is worth noting that we were able to trace the origins of all five parties’ figures, but only with considerable perseverance and fairly sophisticated information seeking techniques.)

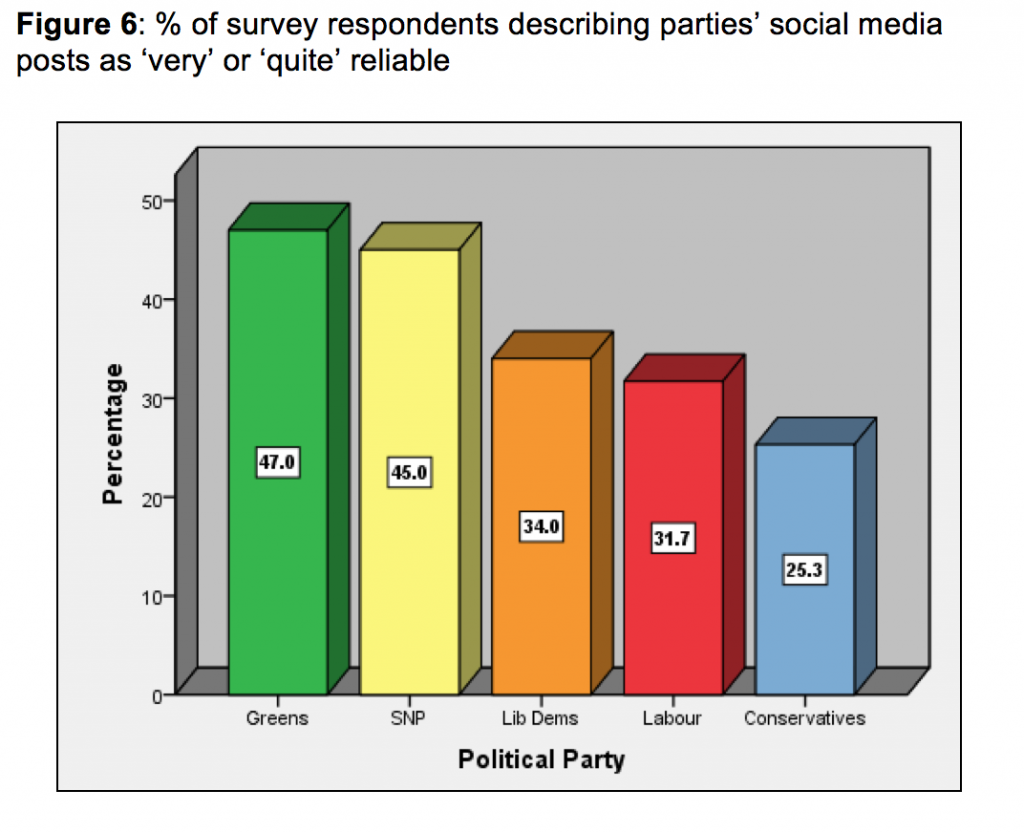

Figure 6 illustrates the proportion of our sample who thought that the statistics contained within the five social media posts would be ‘very’ or ‘quite’ reliable.

As can be seen, the Scottish Greens’ post was viewed as the most reliable, closely followed by that of the SNP. Meanwhile, the Scottish Conservatives’ post on college places was regarded as the least reliable. When questioned further, our respondents highlighted a number of factors that might affect the perceived reliability of political ‘facts’:

As can be seen, the Scottish Greens’ post was viewed as the most reliable, closely followed by that of the SNP. Meanwhile, the Scottish Conservatives’ post on college places was regarded as the least reliable. When questioned further, our respondents highlighted a number of factors that might affect the perceived reliability of political ‘facts’:

Political allegiance. Our participants were asked to indicate if they had a particular allegiance, and when we looked at the answers of those who revealed their preference, a pattern of sorts emerged. This was most obvious amongst the self-proclaimed SNP supporters, 74.5% of whom felt that the ‘facts and figures’ in the SNP’s post were ‘very’ or ‘quite’ reliable (cf. 45% of the entire sample).

Trust in politicians in general. It is fair to say that some of our respondents were very cynical about our politicians, believing most of them to be ‘liars’, ‘cheats’ or ‘charlatans’.

Trust in particular politicians or parties. Some respondents highlighted their lack of trust in particular politicians (who shall remain nameless here). Equally, though, some spoke of hard-working, local constituency politicians who, they believed, were eminently trustworthy. Interestingly, some participants spoke about the overall ethos of the Scottish Greens, suggesting that this inspires a greater level of trust in their political statements and claims (this perhaps partly explains why their social media post was regarded as the most reliable).

Bias and ‘spin’. There was a general awareness amongst our participants that the information provided on parties’ websites and social media sites is unlikely to be entirely objective; and that particular statistics may be ‘cherry-picked’ to support or oppose a political argument.

Sources. A key factor for many participants in gauging reliability was whether or not the source of the ‘facts and figures’ had been given. Having said that, some would remain wary of statistics originating from agencies and organisations with whom they were not familiar.

Personal and professional experience. Many of our respondents spoke about their own life experience being an important factor in determining the reliability of political ‘facts’. For example, those respondents with young families felt they were in a position to confirm the Greens’ claims about childcare costs; while those who had worked in the education sector felt very qualified to comment on the accuracy of the attacks on the Scottish Government’s record in colleges and schools.

When our participants were questioned on where they might go in an attempt to either confirm or debunk politicians’ ‘facts’, a range of (mainly online) sources were cited: the UK or Scottish Government’s websites; the websites of specific government agencies; newspaper and news media websites; and the websites of universities, think tanks, third sector organisations or interest/pressure groups. Some also spoke about using Freedom of Information legislation in pursuit of ‘the truth’. But for the vast majority of our participants, Google would be their first port of call.

The analysis of our data is still ongoing, but one aspect we are currently exploring is that of the ‘journey’ of a political ‘fact’, from its origins in, say, the report of a government agency, parliamentary committee, third sector body, or academic institution, to it being cited regularly by politicians in, say, speeches, media appearances, or social media posts. Perhaps unsurprisingly, our results so far suggest that, as the journey of the fact progresses, its original source becomes less and less clear, and the fact itself is increasingly likely to be reinterpreted to suit the needs and agenda of the political actors using it.

This post represents the views of the authors and not those of Democratic Audit. It first appeared at the LSE British Politics and Policy blog.

Graeme Baxter is a Research Fellow specialising in Information Management at Robert Gordon University.

Graeme Baxter is a Research Fellow specialising in Information Management at Robert Gordon University.

Rita Marcella (centre) is Professor of Information Management at Robert Gordon University.

Agnieszka Walicka is studying for an MSc in Information and Library Studies at Robert Gordon University.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.