The UK government’s imaginative use of evidence to make policy

It is a frequent complaint by public policy academics that the UK government does not follow evidence-based policy, and instead cherry-picks research to further its political priorities to produce ‘policy-based evidence’. However, writes Paul Cairney, evidence is used to inform policy in more ways than these two opposing categories suggest. As illustrated by family intervention initiatives, the cynical and short-term use of evidence to make policy in one arena can provide cover for more sincere and long-term policymaking in another.

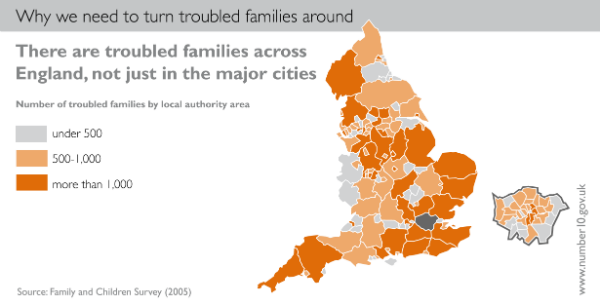

Government infographic for its troubled families policy. Picture: Number 10, via a (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0) licence

The title of this article conveys two meanings of imaginative: negative, as a euphemism for ridiculous, and positive, as a creative way to frame an evidence-informed agenda to address the pressures of Westminster politics. The UK Government’s ‘troubled families’ policy appears to be to be a classic case of the former: a top-down, evidence-light and quick emotional reaction to crisis. It developed substantially after riots in England in August 2011. Within one week, Prime Minister David Cameron made a speech linking behaviour directly to ‘thugs’ and immorality – ‘people showing indifference to right and wrong…people with a twisted moral code…people with a complete absence of self-restraint’ – before identifying a breakdown in family life as a major factor. Cameron reinforced this agenda in December 2011 by stressing the need for individuals and families to take moral responsibility for their actions, and for the state to intervene earlier in their lives to reduce public spending costs in the long term.

Such examples of UK ‘families policy’ are often criticised as a ‘classic case of policy based evidence’: policymakers tell tall tales about evidence to justify ideology-driven action. It is a crucial case study for two reasons: first, it includes several kinds of problematic evidence-use, including:

- Designing a performance management system that is intended to project instant success.

- Linking the need for urgent action to vivid neuroscientific images of questionable value.

- ‘Scaling up’ policy in problematic ways, by getting ahead of the evidence on ‘family intervention projects’ piloted in the UK, and importing projects with more scientific evidence of success but in very different political systems.

Second, it is easy to criticise the UK government’s imaginative use of evidence, but more difficult to say – when viewing the policy problem from its perspective and role in Westminster politics – what the government could and should do instead. So, in a recent article for British Politics, I compare sympathetic versus unsympathetic stories of UK policymaking to highlight the policy problem from different perspectives.

Viewed from the outside, the UK government’s action looks like a cynical attempt to produce a quick fix to the London riots, stigmatise vulnerable populations and hoodwink the public into thinking that the central government is controlling local outcomes and generating success.

Viewed from the inside, however, the policy is pragmatic and informed by promising – albeit often slim – evidence which needs to be sold in the right way. For the UK government there may seem to be little alternative to this policy, given the available evidence, the need to do something for the long term and to account for itself in a Westminster system in the short term.

Let’s explore the implication of the latter assessment in which UK governments use evidence in a mix of ways to describe an urgent problem, present an image of success and governing competence, and provide cover for more evidence-informed, long-term action. The result is the appearance of top-down ‘muscular’ government and a tendency for policy to change as it is implemented.

In other words, it provides the usual weird-looking compromise between ‘evidence-based policy’ and ‘policy-based evidence’ driven by the trade-offs that elected policymakers have to make when faced with the need to act to satisfy a political audience on the basis of evidence use that will never satisfy a scientific audience:

Consequently, there is also a third story which combines elements of the other two. Initially, scholars raise major concerns about the nature and tone of government policy: it is an agenda designed to punish vulnerable populations, not provide cover for supportive policies. Subsequently, they describe a tendency for policy to change as is implemented, such as when mediated by local authority choices and social workers maintaining a commitment to their professional values when delivering policy (2018: 16).

A greater understanding of these routine motives of policymakers can, therefore, help produce more effective criticism when governments engage in problematic uses of evidence.

This article gives the views of the author, not the position of Democratic Audit. It is based on the author’s recent article published in British Politics (Open Access)

About the author

Paul Cairney is Professor of Politics and Public Policy at the University of Stirling. His work on ‘evidence-based policymaking’ can be found here: https://paulcairney.wordpress.com/ebpm/

Paul Cairney is Professor of Politics and Public Policy at the University of Stirling. His work on ‘evidence-based policymaking’ can be found here: https://paulcairney.wordpress.com/ebpm/

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

thanks for sharing such interesting and great post.thanks for sharing such great post.