Audit 2017: How democratic and effective are the UK’s core executive and government system?

As part of our 2017 Audit of UK Democracy, Patrick Dunleavy looks at how well the dominant centre of power in the British state operates – spanning the Prime Minister, Cabinet, cabinet committees, ministers and critical central departments. How effectively does this ‘core executive’, and the rest of Whitehall government, consistently serve UK citizens’ interests? How accountable and responsive to Parliament and the public are these key centres of decision-making?

Theresa May and her Cabinet in September 2016. Photo: Zoe Norfolk/ Number 10 via a CC-BY-NC-ND 2.0 licence

This article was published as part of our 2017 Audit of UK democracy. We have now published: The UK’s Changing Democracy: The 2018 Democratic Audit with LSE Press, available in all ebook formats. You can download the whole book for free, and individual chapters, including a fully revised version of this article.

What does democracy require of the core executive, along with wider central government?

- The core executive should provide clear unification of public policies across government, so that the UK state operates as an effective whole, and citizens and civil society can better understand decision-making.

- The core executive especially, and central government more widely, should continuously protect the welfare and security of UK citizens and organisations. Government should provide a stable and predictable context in which citizens can plan their lives and enterprises and civil society can conduct activities predictably.

- Both strategic decision-making within the core executive, and more routine policy-making across Whitehall, should foster careful deliberation to establish the most inclusive possible view of the ‘public interest’. Effective policy should maximise benefits and minimise costs and risks for UK citizens and stakeholders.

- Checks and balances are needed within the core executive to guard against the formulation of ill-advised policies through ‘groupthink’ or the abuse of power by one or a few powerful decision-makers. Where ‘policy fiascos’ occur the core executive must demonstrate a concern for lesson-drawing and future improvement.

- The core executive and government should operate fully within the law, and ministers should be politically accountable to Parliament and legally accountable to the courts for their actions.

- Policy-making should be as transparent as possible, while recognising that some core executive matters especially may need to be kept secret, for a time. Parliament should always be truthfully informed of decisions and policy plans as early as possible, and House of Commons debates and scrutiny should influence what gets done.

- Policy development should ideally distribute risks to those social interests best able to insure against them at lowest cost. Consultation arrangements should ensure that stakeholders can be easily and effectively involved. Freedom of information provisions should be extensive and implemented in committed ways.

The executive is the part of the state that makes policies and gets things done, while answering in public directly to Parliament and via elections to voters. At UK national level, and across all of England, the executive consists of ministerial departments and big agencies headquartered in Whitehall, each making policy predominantly in a single policy area. This centre also funds and guides other implementing parts of the state – such as, the NHS, local authorities, police services and a wide range of quasi-government agencies and ‘non-departmental public bodies’ (NDPBs).

Within the centre, the ‘core executive’ is the functional apex (or the brains/heart) of state decision-making. In any country it is the set of institutions that unifies the polity and determines the most important or strategic policies. In the UK the ‘core executive’ includes the Prime Minister, who appoints the Cabinet, plus cabinet committees, key ministers in central Whitehall departments, and some top officials in the same departments – especially the Treasury, Cabinet Office, 10 Downing Street staffs, the Foreign Office, the Ministry of Defence, the intelligence services and the Bank of England. The core executive especially makes ‘war and peace’ decisions, shaping the UK’s external relations and commitments, homeland security, strategic economic policies (like austerity, national debt and deficit financing), and the direction of broad policy agendas from the top (like Brexit). Parts of the core executive’s activities are shrouded in secrecy, and much remains confidential.

Recent developments

In the 2015 general election David Cameron secured a narrow Conservative majority in the Commons. The result seemed to signal the resumption of ‘normal service’ for peacetime government in Britain. The apparatus of the five-year Conservative-Liberal coalition government was swept into the dustbin. The post of Deputy PM, which had been held by Nick Clegg, returned to the cupboard of history. And the inner co-ordination committee of four (Cameron, George Osborne at the Treasury, Clegg and Danny Alexander, Chief Secretary at the Treasury) that had kept the coalition operating smoothly for so long, was scrapped. Cameron kept Whitehall’s department structure largely unchanged, as he had under the coalition, and ruled mainly with Osborne. Boris Johnson (a possible leadership succession contender) was brought into the Cabinet in a minor role.

Jockeying between the relatively few Cabinet Eurosceptics and the ‘Cameroons’ became more vigorous as the PM moved to deliver on his election pledge (dating from 2013) to hold an in/out referendum on the European Union. But in the end it was the committed Eurosceptic Michael Gove and the more diffident late-convert Johnson whose campaigning caused the ‘doom and gloom’ Brexit campaign to be lost on 23 June 2106. Cameron resigned the next morning.

From the ensuing chaos of an aborted Tory leadership contest (in which Gove and Johnson both imploded early on), Theresa May emerged as winner, becoming PM after a two week interregnum. She signalled a pattern of strong central control from Downing Street by keeping only three out of 24 Cabinet ministers in the same roles as before, promoting Johnson to the Foreign Office, and exiling Gove (for a year) and Osborne (for good). She created two new Whitehall departments for major Eurosceptics David Davis and Liam Fox to run key Brexit functions. A very centralist 10 Downing Street operation was headed by two powerful staffers who had followed May from the Home Office (Nick Timothy and Fiona Hill). In a speech at Lancaster House, May outlined a ‘hard Brexit’ stance, which toughened up the referendum vote decision into a commitment to re-control all immigration and exit fairly completely from all EU institutions and arrangements.

This regime collapsed within a year, after May reversed her previous public pledges and called a general election (which Jeremy Corbyn’s Labour agreed to under the terms of the Fixed Term Parliament Act). What seemed like a smart move for May, and a suicidal one by Corbyn, turned out to be exactly the opposite, with May losing her majority of MPs in June 2017. The government clung to power only by negotiating a ‘confidence and supply’ agreement with the 10 MPs from the Northern Ireland Democratic Unionist Party (DUP), at a reputed minimum cost of a £1bn ‘bung’ for public spending there. May’s closest advisors, Timothy and Hill, were blamed for the disastrous Tory manifesto and hounded from office by Tory newspapers and MPs. A more outwardly ‘consensual’ regime for running the Conservative parliamentary party was put in place, with a new Deputy PM, the more accommodating Damian Green.

The new government ran into immediate trouble, failing to trigger the COBRA emergency committee for the Grenfell Tower fire disaster, where the initial state response had compounded the catastrophe. Tensions over the hard Brexit strategy within the Conservative parliamentary party created a very different situation from the ‘strong and stable’ platform that May had said the early election would secure for her. The government abandoned practically all the controversial components of the damaging Tory manifesto, and May called for inter-party co-operation. But the PM was living on borrowed time and her administration could not seem to get a modus operandi for liaising more constructively on Brexit with Labour or the devolved governments in Scotland and Wales, whose legislative consent will probably be needed.

Amidst these travails, the 2016 official post mortem report into the UK’s 2003 joining of the Iraq invasion by Sir John Chilcot’s commission (five years in the making and running to 15m words) was soon lost to view. It painted a bleak picture of the UK’s core executive at that time. Blair as PM and his communication chief (Alastair Campbell) clearly steamrollered military action through the Cabinet and Parliament with false information – a ‘dodgy dossier’ alleging that Saddam Hussein’s Iraq had ‘weapons of mass destruction’, which in fact did not exist.

Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities, Threats (SWOT) analysis

| Current strengths | Current weaknesses |

|---|---|

| British government before 2010 was normally strongly unified, with clear Prime Ministerial and Cabinet control, strong ministerial roles within Whitehall departments, single-party or close-knit coalition governments, and relatively clear and distinct strategic policy stances. Some of these features were briefly visible again in 2016-17. | The PM’s ‘three As’ powers are extensive. They appoint cabinet ministers, allocate their portfolios and assign policy issues across departments. Theoretically they can so arrange ministers’ policy trade-offs that they will perfectly implement the premier’s preferences. Most ministers are highly dependent on the PM’s patronage and access for influence. |

| Cabinet government and the extended cabinet committee system provide key checks on the power of Prime Ministers and their 10 Downing Street office. They foster greater deliberation before policy commitments are made, and a balanced approach, with the different departments ideally representing diverse stakeholders’ interests and wider public reactions. | In pursuit of purely political advantages, PMs have often rejigged ministerial roles by pushing through reorganisations ‘making and breaking Whitehall departments’. This administrative churning is costly, short-termist and disruptive, reaching a peak under the Blair and Brown governments. A moratorium on reorganisations followed under Cameron’s premiership (2010-16), only to be succeeded by drastic changes under May in June 2016. |

| Decisions within the core executive are normally made on far more than a simple majority rule (51% agreement). Instead an initial search looks for a high level of consensus across ministers/ departments. This may give way to deciding on a lesser but still ‘large majority’ (e.g. 60% agreement) basis, especially in crises or situations where the status quo is worsening. | Cabinet decision-making no longer operates in any effectively collegial manner. PMs control the routing of issues through committees and can bypass them via ‘bilaterals’ and ‘sofa government’. Strong government communications integration enforces complete solidarity across all ministers, without any guarantee of participation in decisions. Ministers mainly fight back by ‘adversarial leaking’, in turn routinely denied. |

| Because of these processes, the principle of ‘collective responsibility’ binds Cabinet ministers to publicly back every agreed government policy, and not to talk ‘off their brief’. Wider ministerial solidarity also requires all junior ministers to follow the government line (e.g. resigning if they do not vote the government line in the Commons). | The UK still has a ‘fastest law in the West’ syndrome, with the fewest checks and balances of any liberal democracy on the PM or the core executive – especially in one-party governments with secure Commons majorities. Decisions can be (and often are) made ‘lightly or inadvisedly’. Ministers can simply escape any unfavourable consequences of bad policies through party loyalties making them invulnerable in the legislature. |

| Policy-making can take place swiftly when needed. Whitehall’s resilience in crisis-handling and capacity to respond to demanding contingencies are generally high. | Recurring ‘groupthink’ episodes have produced major ‘policy fiascos’ – most recently the UK’s involvement on false grounds in the 2003 invasion of Iraq; the disastrous 2011 armed intervention with France in Libya; and Theresa May’s calling of an early general election in 2017. Arguably the UK is more prone to major ‘policy disasters’ than other liberal democracies. |

| UK institutions are long-lived and can draw on a strong tradition of relatively effective government, confident and immediate administrative implementation of ministerial decisions, and (normally) high levels of public acceptance and legitimacy. It is expected that the government will consult (most) affected interests on major policy changes, but ministers often choose to ignore or override the feedback received. | There is little evidence of much substantial policy-learning capacity within the core executive. All British PMs back to Stanley Baldwin (in 1935) have been forced to retire by election defeats, coups against them within their own parties, or illness. None has retired to acclaim as a successful leader. |

| All ministers sit in Parliament and are directly and individually accountable there for their actions. The Freedom of Information (FOI) Act secures public transparency. Modern media, interest group and social media scrutiny is intense, rapid and fine-grained. | Long-running dyadic power conflicts have occurred between PMs and key ministerial colleagues (especially the Chancellor or Foreign Secretary). These have been the main exceptions to Prime Ministerial dominance. Here a powerful minister (often an alternate leadership contender) can amass enough influence with colleagues to exercise a ‘blocking veto’ on what the PM wants to happen in key policy areas, usually those related to their brief. Under large majority rules this frustrates implementation of the PM’s preferred policy. It either results in inaction, or on extra time being spent to achieve a bargained compromise between the PM and the vetoing minister. Notable cases include Thatcher-Lawson/Howe conflicts on EU policy (1985-90), the Blair-Brown public spending conflicts (1997-2007), Cameron-Clegg tussles (2010-15), and post-Brexit referendum disagreements within the May governments (2016-17). |

| Ministerial decision-making operates in a climate of pervasive secrecy (still enforced by the Official Secrets Act). Ministers often withhold information from Parliament, reject FOI requests on questionable grounds, and manipulate the flows of information to their own advantage. They incur only small costs when found or, unless a scandal takes root. |

| Future opportunities | Future threats |

|---|---|

| Over the 43 years of the UK’s membership of the EU, Westminster ministers lost power to Brussels. Perhaps unconsciously British elites compensated by focusing more and more attention on ‘micro-managing’ the public services still within their control in the UK and in England and being implemented by regional or local bodies. This strong centralisation dynamic was checked only by some 'organic' devolution. Now that the UK is leaving the EU, many lost central government competences need to be re-built to ‘take back control’ of trade and economic policy. A post-Brexit re-focusing may encourage ministers and Whitehall to ease up on trying to fine-control public services that are best run at regional or local levels. At the least the burden of Brexit-related laws will squeeze opportunities for other kinds of domestic legislation. | The Brexit process will remove a whole set of checks and balances on UK decision-making that have operated for 43 years at EU level in Brussels. These mainly enhanced stability and a long-run perspective in policy-making. As a result, the organisational culture of more short-termist and failure-prone modes of decision-making (that prevail in defence, foreign policy and welfare state management) may reinvade key parts of UK policy, especially in economic regulation, innovation and environmental policies. |

| Working through the Brexit process will take many years and entail one of the largest and most demanding shifts in public policy-making of the last three decades. Many observers doubt that ministers and Whitehall will be able to respond well to this challenge. | |

| The May government apparently envisages relying heavily on ‘Henry VIII’ clauses in Brexit legislation, which would allow ministers to vary inherited EU laws using hard-to-scrutinise statutory instruments instead of new legislation in Parliament. | |

| In the 2016-17 period there were disturbing signs of another eminently foreseeable policy fiasco emerging through Conservative ministers’ partisan stress on following a ‘hard Brexit’ strategy, whose economic costs could be high. |

Policy fiascos and disasters

Critics argue that major problems arise from the lack of checks and balances in the UK core executive. This interacts badly with the ‘legacy’ hangovers of an over-strong executive government tradition using Crown prerogative powers, and a lingering British empire tradition of foreign and defence policy-making that is insulated from public opinion and elite-dominated. These factor combine to make the UK uniquely vulnerable to large-scale but perfectly foreseeable policy fiascos or disasters. This is especially true where a PM and close advisors fall prey to ‘groupthink’, as May and advisors clearly did in triggering the 2017 early general election. Other observers see UK ministerial elite as being too powerful vis-à-vis their ‘generalist’ civil servants, able to order that ill-advised policy is implemented. Neither politicians nor their Whitehall advisors are masters of specialist subjects, compounding a long succession of smaller-scale ‘blunders’.

In strategic policy making the most recent policy fiasco was the UK’s joint military intervention with France into the civil war in Libya in 2011, aiding the anti-Gaddafi rebels with frequent air strikes, SAS ‘advisors’ and plentiful arms supplies. Both the intervening countries ran out of bombs and missiles within weeks of the conflict starting, and had to be re-supplied covertly by the USA which nominally was not involved. A lot of Gaddafi regime infrastructure was destroyed, and plentiful arms supplies sent to assorted rebel militias. The regime was duly toppled, but Libya descended into near-permanent lower intensity civil war and ‘failed state’ status. A Commons committee concluded that planning for the aftermath of intervention was minimal and ham-fisted.

As a result, greatly increased flows of refugees began crossing the Mediterranean to reach EU countries, creating part of the anti-immigrant momentum that fuelled the anxieties of the UK’s Brexit voters five years later. And Islamic jihadist forces (such as Isis and al-Qaeda) soon secured toeholds in the Libyan stalemate chaos. The arms initially sent into Libya also spread into all neighbouring countries, reaching Islamic jihadists as far south as Nigeria and Chad. Little wonder that Barrack Obama publicly described the episode as the ’worst mistake’ during his presidency, and in private reputedly called it ‘a shit show’.

The Libya commitment reflected an over-homogenisation of views by the PM and colleagues, and an over-confidence (bordering on delusional) about the UK’s state capacities in the modern world. However, conflicts inside the core executive can also lead to policy fiascos, as with David Cameron’s repeated failure (like his Tory predecessors) to manage the Conservative Eurosceptics. Cameron alighted on the pledge of an in/out referendum in early 2013 as a tool to keep their dissidence under control in the short term. But as the pledge hardened and UKIP boomed in 2014, Cameron began to make a drip-drip of extra concessions to his far-right ministers and MPs.

After the 2015 election, this culminated in the suspension of collective cabinet responsibility during the referendum campaign, so that Eurosceptic ministers need not resign their posts, despite publicly contradicting everything that the PM and Chancellor were saying. Arguably this was what led to the Brexit vote outcome. Critics see it a profound failure of the key requirement for the core executive to provide unified control, albeit with checks and balances. The vacuum of leadership that opened up for two weeks or more after Cameron’s resignation spoke to this collapse of the core executive’s role – as did the Tories’ subsequent aborting of the leadership campaign, with all of Theresa May’s rivals withdrawing.

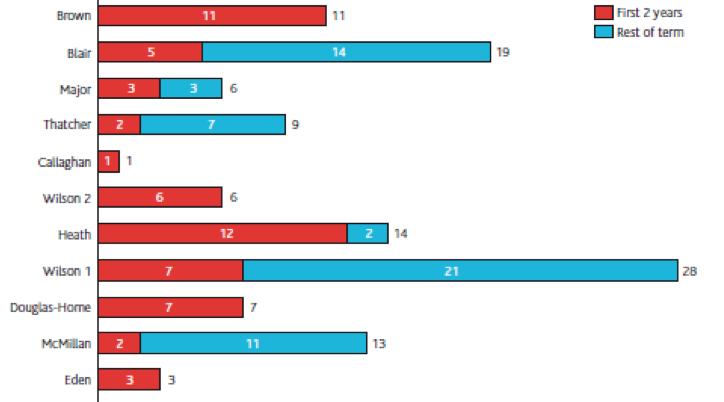

Making and breaking Whitehall departments

One of a Prime Minister’s most potent uses of Crown prerogative powers involves their unilateral control over the structure of Whitehall departments. PMs can scrap, merge, de-merge and reorganise ministries at will, often creating new ones to reflect their priorities or to respond to external changes. Chart 1 below shows that in the post-war period there were two periods of rapid reorganisation, in the late 1960s/early 1970s, and under the modernising Blair and Brown ‘new Labour’ governments. Most redesigns occur in the first two years of a premiership. Research shows that political priorities in cabinet-making priorities dominated administrative ones in most of the reorganisations – many of which were done by PMs in a great rush and with little or no planning. The past level of churn in Whitehall structures made the UK exceptional amongst OECD countries, and stood out even when compared with other ‘Westminster system’ countries.

Chart 1: Major reorganisations of Whitehall departments

Source: White and Dunleavy, 2010, Figure 8, p. 20.

In 2010 David Cameron decided not to reorganise Whitehall, which he saw as a costly distraction when the UK’s priority was cutting public sector deficits. (His Tory health minister, however, pushed through a costly and pointless ‘reform’ of NHS governance’). Throughout Cameron’s five years running a coalition government he could not act alone, since ministerial appointments formed key parts of the coalition agreement, although he reshuffled Tory ministers a bit. In 2016 he continued this stance, so that the UK seemed to be acting more like a standard OECD country with stable department structures.

All this changed under Theresa May, who created two completely new ministries – DExEU, the Department for Exiting the European Union to manage the withdrawal process; and DIT, the Department for International Trade, to resume the trade deals role previously assigned to Brussels, and in which the UK lacked all expertise. May also reconfigured two existing departments in major ways, setting up BEIS, the department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy, and moving universities and research back to the Education department. Both DExEU and DIT look as if they may not last long, and an alternative strategy would have been to create a neutral Cabinet Office unit to run Brexit negotiations.

The Cabinet committee system

Below the large, 24-member cabinet, the Westminster system has traditionally operated one of the most elaborate committee systems of any liberal democracy. All relevant cabinet departments sit on related committees, but in the past there were many more committees, arranged in a complex hierarchy. ‘Prime ministers decide how to organise [committees], who to appoint to them, and how actively they are involved in them’.

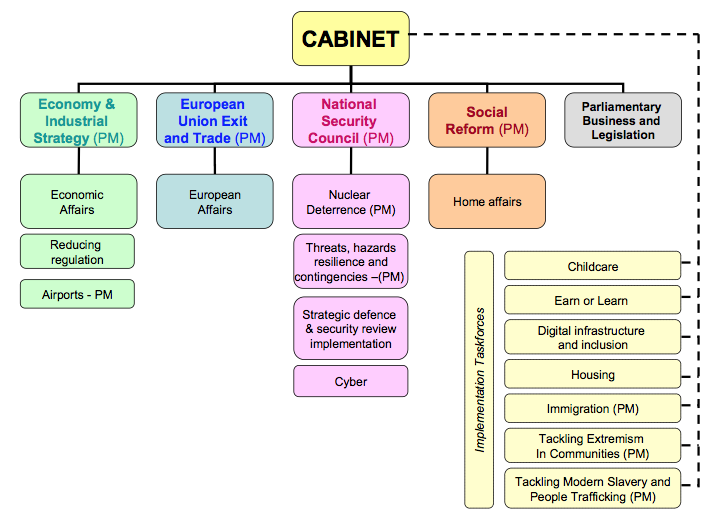

However, Nicholas Allen recently demonstrated that:

May has streamlined the committee system she inherited from David Cameron. Instead of ten committees, ten subcommittees and eleven ‘implementation taskforces’ (bodies introduced in 2015 to drive forward the government’s ‘most important crosscutting priorities’) [31 major bodies in all], there are now just five committees, nine subcommittees handling regular business, and seven taskforces [21 major bodies, shown in Chart 2 below]. [Our italics]

Chart 2: May’s cabinet committee structure in summer 2016

Note: (PM) shows PM chairs body

Almost half of these new bodies were chaired by the PM herself (as shown), including all the main substantive committees, a historically unusual level of centralisation. The Leader of the Commons chaired the only other full Committee, scheduling legislative business. The Chancellor and Home Secretary chaired two sub-committees each, and the Business Secretary and Party Chairman chaired one. Three other ministers chaired one or two Taskforces, which on past form may meet irregularly or infrequently.

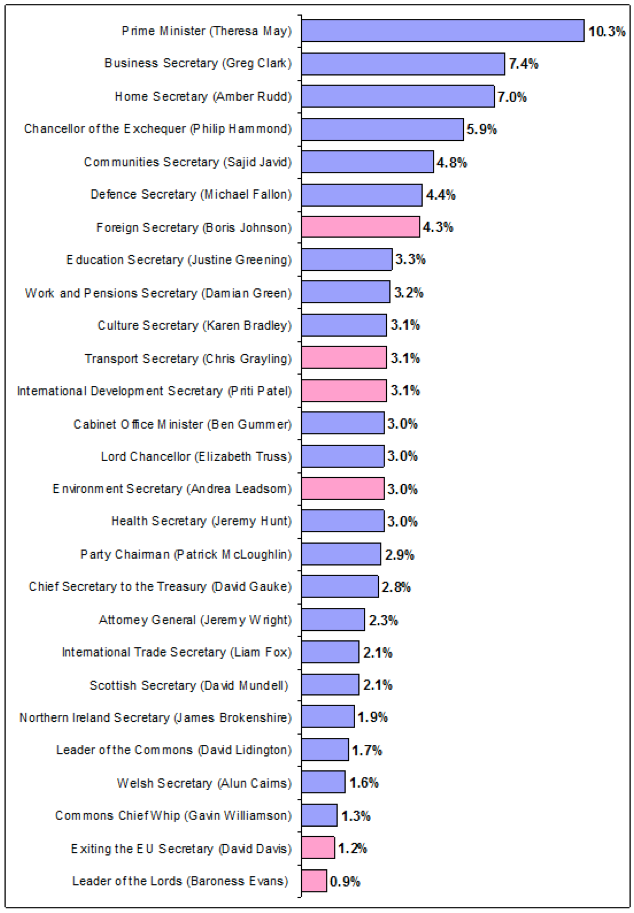

Using a counting and weighting system applied to committees in all UK governments since 1992, we can calculate the ‘positional power’ of ministers in terms of their places, and their share of the total. Chart 3 shows that the new bigger committees and some sub-committees give a place to almost everyone on almost everything, so that the PM’s share of positional power is less than 11 per cent. Comparing earlier research shows that May’s number is greater than John Major’s 7.6% score in 2001, but down on Tony Blair’s score of 14.9% in 1997.

Chart 3: The positional power of Cabinet members in the cabinet committee system, in summer 2016

Source: Allen, 2016.

Note: Ministers in pink are prominent Brexiteers.

Of course, positional power is not the only kind of power that ministers have, as the low rank for David Davis (one of the most powerful ministers under May) shows. Allen showed that in the 2010-15 coalition government the Liberal Democrats had more positional power in the committee system than they did cabinet posts (where they had five out of 23). But this positional power was invisible to the public, who saw the government as Conservative-dominated.

Amongst the several other power bases that matter, ministers control substantial administrative power by holding their own department fiefdoms, where they control key policy-making functions, and shape how a lot of public money is spent. Informal coalitions of ministers may have ‘blocking power’ to delay or frustrate decisions under the ‘large majority’ rules that prevail in executive decision-making. Other ministers may be politically powerful because they have the PM’s ear. And some cabinet top ministers can become credible leadership succession candidates, with their own followings in the government party’s MPs (and perhaps amongst other ministers looking to the future).

Running the committee system and keeping track of what departments have committed to do, and of their progress in meeting targets, is the Cabinet Office secretariat. It provides a strong administrative core, ensuring that decisions and commitments are carefully recorded and then chased up.

Budgetary control within government

The other core co-ordination mechanism is tight Treasury control of public spending, which reached a peak under the Cameron governments’ austerity programmes. The budgets for the NHS and overseas aid were maintained in real terms between 2010-16 (although NHS spending fell below the amounts needed for a real standstill budget). But this just meant that the burdens elsewhere, on other domestic, welfare and defence spending were intensified. An Expenditure Review Group formed from the Treasury and Cabinet Office did a reasonable job, at first, of damage limitation in implementing cutbacks, using a ‘do more for less’ strategy. David Cameron commented complacently in 2014: ‘It must be said, at the time, all manner of horror show predictions were made about what would happen to our country. But what actually happened?’ However, by this time in fact real cuts in programmes, crude ‘do less for less’ strategies had almost completely taken over, with Whitehall simply passing the need for huge cost cuts down to local authorities, police forces, the armed forces and NHS bodies which could cope only by cutting out services.

The apparatus of Treasury control make it one of the world’s most powerful ‘finance ministries’. It ‘focuses on managing a number of interrelated systems that taken together provide the basis for spending control in the context of substantial delegation to other actors’, according to one study. In preparing three-year spending reviews the Treasury conducts detailed ‘bi-lateral’ negotiations with spending ministries. It also has a set of macro-controls over budget sectors, which they use to hold departments to spending totals between reviews, but with some departmental autonomy within agreed totals.

Yet micro budget controls (such as limits on viring unspent monies from one heading to another, and ‘clawing back’ unspent funding at the year end) also remain. And staff and expertise cuts within the Treasury itself have drastically reduced its understanding of where spending occurs, or why. For example, many government ‘blunders’ have revolved around IT schemes and big capital investments, for which there are several different but inadequate major project evaluation systems. And UK central government has never yet had any coherent programme for improving government sector productivity.

The ‘secret state’ within Whitehall

Much of the Chilcot report on the disastrous Iraq intervention dealt with the UK’s still substantial secret state, the last remnant of the British empire’s worldwide reach. The main intelligence and security services are:

- MI5 (internal security),

- SIS or MI6 (overseas intelligence),

- GCHQ (electronic and other tech surveillance),

- the Defence Intelligence Staffs (military intelligence)

Their activities are supervised by the Joint Intelligence Committee (JIC) in the Cabinet Office, which coordinates and sanctions major operations, reporting to the PM. Following the ‘dodgy dossier’ episode where intelligence was manipulated by the PM’s aides, Whitehall confidence in the quality of information from the four agencies and the Joint Intelligence Committee took several years to rebuild.

The UK is bound into close working relationships with the US intelligence agencies, with SIS linked to the CIA, and GCHQ working hand-in-glove with the US National Security Agency. Less important strong links are to agencies in Australia, Canada and New Zealand, and also to those in a few major European states and EU agencies.

A single Cabinet Office intelligence expenditure vote of £2.5bn is declared to Parliament but not further explained in public. Around £85m to £100m of undeclared intelligence spending is still padded around the Cabinet Office budget, with further amounts in defence. The only Parliamentary control over any of this comes from the Intelligence and Security Committee, whose members are ‘trusties’, hand-picked by the PM from the Commons and Lords.

The UK also has developed inter-departmental homeland security arrangements which focus on the COBRA meeting (an impressive acronym that actually stands for the mundane Cabinet Office Briefing Room A, where its meeting take place). In principle, the resilience system is also supposed to also cover civil contingencies (such as foot and mouth disease and flooding in the past). But COBRA never met over the 2016 Grenfell Tower disaster, and government co-ordination in the aftermath was very poor.

These highly non-transparent arrangements have fuelled persistent controversy about the existence of an ‘inner state’, one that controls the drone killings of terror suspects in military action zones overseas, and some extra-legal actions of homeland security or army special forces (which for certain included extra-judicial assassinations in Northern Ireland and perhaps in Afghanistan in earlier periods). The Snowden revelations suggested that GCHQ had done a ‘buddy deal’ for many years with the NSA to bulk spy on US citizens (which the US agency cannot legally do), in return for the NSA trading back the same information for UK and European citizens (which GCHQ cannot legally do). SIS has been accused of colluding in torture implemented by US agencies in Iraq and Afghanistan in 2002-08, using information gained from a rendition programme where prisoners were sent for interrogation to torture-using US-allied states.

Routinely denounced by elite insiders as ‘conspiracy theories’, these allegations have none the less gained added contextual credence from the long-run and now well-documented cover-ups of policy fiascos perpetrated elsewhere by the UK state establishment – such as those over mass deaths in 1989 at the Hillsborough football stadium; and over the poisoning of NHS patients over many years with hepatitis B from US-imported blood.

Conclusions

The UK’s core executive once worked smoothly. It has clearly degenerated fast in the 21st century. Westminster and Whitehall retain some core strengths, especially a weight of tradition that regularly produces better performance under pressure, reasonably integrated action on homeland security for citizens, and some ability to securely ride out crises. Yet elite conventional wisdoms, which dwelt on a supposed ‘Rolls Royce’ machine, are never heard now – after six years of unprecedented cutbacks in running costs across Whitehall; political mistakes and poor planning over Libya, Afghanistan and Iraq; and the unexpected loss of the Brexit referendum. Now the looming threat of leaving the EU on poor economic terms under a ‘hard Brexit’ strategy seems to cap a very tarnished recent record.

The clouds in the form of recurring ‘policy disasters’ and ‘fiascos’ are also gathering. Both the Conservative and Labour party elites and leaderships seem disinclined to learn the right lessons from past mistakes, or to take steps to foster more transparent, deliberative and well-considered decision-making at the heart of government. Like the Bourbon monarchs, the fear might be that they have ‘learnt nothing and forgotten nothing’.

This post does not represent the views of the LSE.

Patrick Dunleavy is Professor of Political Science and Public Policy at the LSE and co-director of Democratic Audit.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.