Accountability in a one-party system: the task of gauging public opinion in Vietnam

Vietnam is a one-party state: it is characterised variously as ‘not free’, ‘developmental’ and ‘responsive-regressive’. Dennis Curry explains how the UN Development Programme and a local think-tank worked together to get an insight into what citizens think of public service delivery and local governance. Their PAPI survey shows a growing concern for the environment, although it is not clear whether people genuinely prioritise it above anti-poverty policies. PAPI results have encouraged the Vietnamese government to address the problem of corruption.

Ha Tinh province, 2016. Photo: Bé Râu via a CC-BY-NC 2.0 licence

Under the Sustainable Development Goals framework all UN member states have committed, under goal 16, to promote “effective, accountable and inclusive institutions”. The United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) has been working with national partners in Vietnam to collect citizen feedback on the performance of local government in an annual survey, the Viet Nam Provincial Governance and Public Administration Performance Index, or ‘PAPI’ for short. In Vietnam’s one-party political system, this survey, which grew from pilots in 2009 to become a full national annual survey of all 63 provinces, has become a widely referenced tool for policy making and planning at both the provincial and national level.

UNDP and the Centre for Community Support and Development Studies, a national think-tank, partnered with the Centre for Research and Training of the Vietnam Fatherland Front (VFF) to design surveys seeking citizens’ views of local level governance and service delivery. (The VFF is an umbrella group of mass organisations, mandated in the Constitution of Vietnam and which is aligned to the Communist Party. It is mandated, among other functions, to ‘collect and summarise opinions and petitions of voters and the People for reporting and proposing them to the Party and the State’.) UNDP brought to the table global best practice in social audit tools and survey analytics, drawing on experts in academia.

Over time, the survey has grown to a point where it now collects input from over 13,000 citizens annually, on six dimensions of governance:

i) participation at local levels

ii) transparency

iii) vertical accountability

iv) control of corruption

v) public administrative procedures

(vi) public service delivery.

These are further broken down into 22 sub-dimensions measured by over 90 indicators.

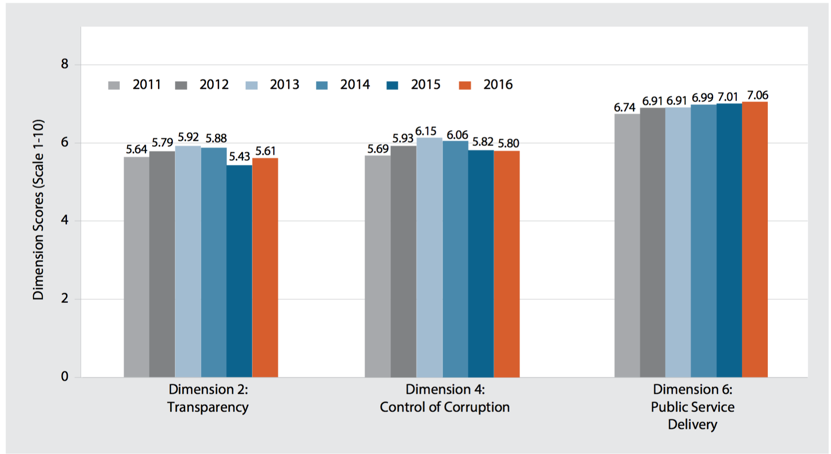

Figure 1: PAPI mean scores by dimensions, 2011-16

This has allowed the tracking of national trends of citizens’ experience of governance. The data shows, for example, that people’s satisfaction with public service delivery has steadily increased over time, while perceptions of transparency and control of corruption have varied but remain flat overall.

At the same time, profiles of individual provinces allow local governments to see their area of strengths and weaknesses, as perceived by citizens, and develop policy and planning responses that will improve citizens’ experience of governance.

PAPI 2016 Report – highlighting growing concern for the environment

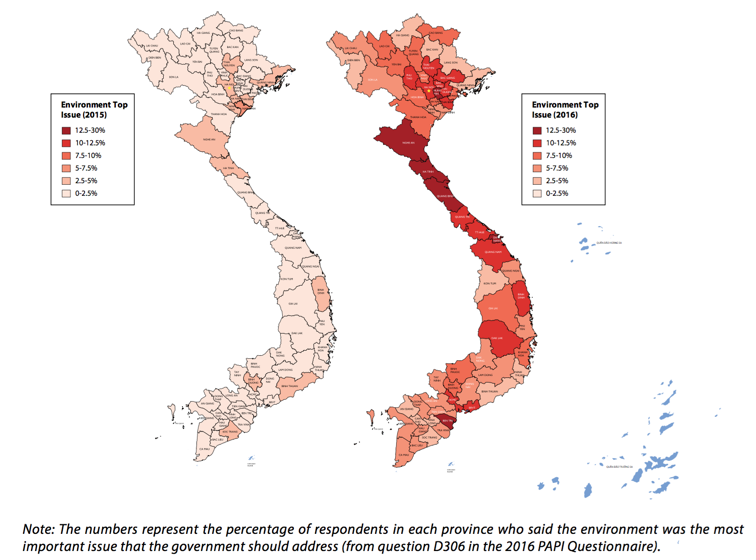

Fig.2: Percentage of citizens indicating environment as top concern facing the country, 2015-16

The most recent survey, launched in April 2017, highlighted many interesting trends. Positive areas of progress included a leap in the proportion of citizens receiving public health insurance from 62% to 74% in one year. Perhaps the most notable challenge to emerge is a striking increase in citizens’ concern for the environment. The survey asks respondents to list and rank the top three concerns facing the country, and while poverty remained the top concern, environment jumped from being mentioned by 2.2% of respondents in 2015 to 12.5% in 2016. This is largely reflective of specific environmental issues that rose to national prominence in the preceding year, most notably a massive ‘fish kill’ along the central coast of Ha Tinh province and southwards due to industrial pollution. Taiwanese steel corporation Formosa was blamed for the pollution. In the same year, the Mekong delta was affected by drought and saline intrusion, and high air pollution in Vietnam’s larger cities drew attention of national and international media.

Deeper analysis of the data shows stratification along geographic and educational lines when it comes to this concern for the environment. Not surprisingly, the districts more directly affected by the fish-kill disaster showed a marked increase in concern for the environment. Of those with post-secondary education, 13% listed the environment as a top concern, while only 4% of those with primary level or below did.

Recognising that governance involves trade-offs when setting policy and expenditure priorities, the survey sought to test how people measure their support for environmental protection against other issues. It asked respondents to choose which of the following statements they agree with:

- “Protection of the environment should be given priority, even at the risk of economic growth.”

- “Economic growth should be given priority even if the protection of the environment suffers.”

77% of respondents in Vietnam chose the first statement. When compared with similar surveys elsewhere, this is below the 82% reported in China but ahead of 64% in Japan and 47% in Indonesia. Citizens are willing to sacrifice economic growth in order to ensure that the environment is protected. However, given that poverty reduction remains citizens’ top priority, this should be read with an awareness that for many citizens ‘economic growth’ may be an abstract term disconnected from daily life. A further question that tested responses to a hypothetical election candidate’s policies supported the hypothesis that respondents place environmental protection ahead of economic growth, but prioritising poverty reduction was still well ahead of both in terms of predicted vote share.

Policy responses to PAPI

Over time, and as the survey results reached a broader audience, policy responses at both the local and national level have become more evident. To date, 39 of Vietnam’s 63 provinces have developed action plans or issued resolutions to respond to PAPI’s findings and promote more responsive local governance, demonstrating the ‘healthy competition’ the survey intends to promote. (For example, Ho Chi Minh City decided “to focus on improving the improvement of the six contents of the PAPI index, striving to implement the next year’s figures higher than the previous year to show the efforts of the government”.) UNDP and partners have facilitated knowledge exchange between provinces, so that good policy and planning practices can be shared (61 provinces have hosted PAPI diagnostic workshops since 2009). At the national level, the survey has supported political action on sensitive issues like corruption. Previous annual surveys reported a high frequency in ‘informal payments’, particularly for access to land use rights certificates (LURC). In 2016 the Ministry of Natural Resources and Environment launched a hotline for citizens to report on bribery during the LURC acquisition process. The PAPI survey later that year reported a reduction from 44% to 23% in such payments, while payments in other areas such as public healthcare services increased in the same period.

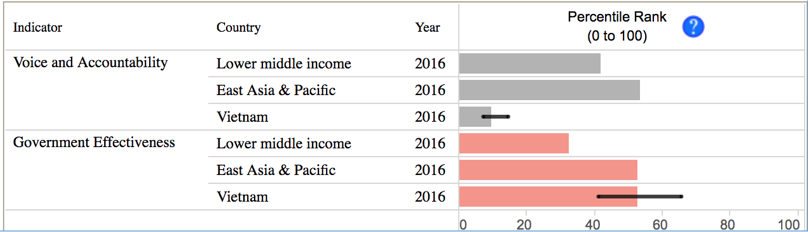

Vietnam is a country that, against a backdrop of 30 years of rapid economic development, receives criticism for deficiencies in democratic governance and human rights protection. The World Governance Indicators developed by the World Bank show that while Vietnam ranks low for ‘Voice and Accountability’ it meets the regional average and exceeds other lower middle income countries for government effectiveness.

This shares characteristics with the international political economy categorisation of ‘developmental state’, of state-led development prioritising economic development at the expense, if needed, of certain democratic norms. Others have sought to describe the state-citizen relationship in Vietnam as ‘responsive-repressive’, with the state sensitive to the needs of citizens (responsive), but with strict limitations and intolerant (repressive) of any actions that are perceived to threaten political or social stability. (Freedom House ranks Vietnam as ‘not free’.) The ‘fish death’ incident can be examined under this lens, with protests and press coverage restricted, while a visible effort was made to assign responsibility and demonstrate accountability.

Within this political framework, the policy responses to PAPI demonstrate how the state responds to the diverse and changing concerns of citizens. In turn, the tool itself serves as an effective mechanism to strengthen the linkage between state and citizen, give voice to people, and promote accountability in governance. Looking ahead to 2030, with the measurement of SDG 16 requiring innovations beyond the frameworks of the preceding Millennium Development Goal era, PAPI contains many lessons in measuring effective governance.

Reference

“Governance, Development, and the Responsive–Repressive State in Vietnam”, Benedict J. Tria Kerkvliet, Forum for Development Studies, Volume 37, 2010 – Issue 1.

This post represents the views of the author and not those of Democratic Audit.

Dennis Curry served as Assistant Country Director, Governance and Participation, for UNDP in Viet Nam from November 2014 to July 2017.

Dennis Curry served as Assistant Country Director, Governance and Participation, for UNDP in Viet Nam from November 2014 to July 2017.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.