Audit 2017: How democratic is the overall set-up of devolved government within the UK?

Devolution in the UK encompasses a range of quite different solutions in three countries (Scotland, Wales, and Northern Ireland), plus lesser delegations of powers to London and some English cities. Designed to meet specific demands for national or regional control and to bring government closer to citizens, there are important issues around the stability and effectiveness of these arrangements. As part of the 2017 Audit of UK Democracy, Diana Stirbu and Patrick Dunleavy explore how far relations between Westminster and the key devolved institutions have been handled democratically and effectively.

At the Auld Acquaintance Cairn in Gretna Green, opponents of Scottish independence left messages of support for the No campaign. Photo: summonedbyfells via a CC-BY 2.0 licence

This article was published as part of our 2017 Audit of UK democracy. We have now published: The UK’s Changing Democracy: The 2018 Democratic Audit with LSE Press, available in all ebook formats. You can download the whole book for free, and individual chapters, including a fully revised version of this article.

What does democracy require of the UK’s devolution arrangements?

- Devolved institutions must be representative and legitimate. They must rely upon freely and fairly elected institutions, built on and promoting democratic principles. Regional and local democracy should bring decision-making closer to the citizens. Devolved institutions should be created with popular endorsement to strengthen their legitimacy.

- Devolution arrangements should be transparent and intelligible to the people they serve. The powers and competences devolved (i.e. what functions are exercised and by whom?) should be clear. And to the relationship between devolved authorities and the central government should be easy to follow. Clear and coherent devolution arrangements are essential if the general public are to hold decision-makers accountable, and are key for decision makers at all levels of government in helping more effective decision making.

- Under the principle of subsidiarity genuine scope for decision-making should be located as close to citizens (as low down in a governance hierarchy) as possible. This is to ensure that decisions attract consent, and interventions take place at the most effective and appropriate level of intervention.

- Autonomous development is best fostered where devolved institutions can decide on their own democratic arrangements – electoral arrangements, size and nature of their political institutions, etc.

- Devolved institutions should be inclusive, and promote citizen participation by creating new venues and mechanism for engagement on a wide range of issues: from early constitutional deliberation on the form and nature of self-governance adopted, through to the policy making process within the new system

- Democratically elected institutions must be able to effectively scrutinise the exercise of power at their appropriate level of government.

- Constitutional and (or) legal protection is needed if democratic devolution is to work, requiring a formal, fair and clear mechanism of resolving disputes over powers and competencies between tiers of government. The UK central government and Westminster Parliament need to ensure that devolved administrations do not trespass on their legislative competence, whilst devolved administrations require a measure of security against central interference. A system of inter-governmental relations is needed to facilitate dialogue and negotiation between the different levels of authority.

- Building new institutions takes a long time. So the arrangements of devolved governance should be durable and resilient in the face of political changes internally in their country or region, and at the UK level.

Most liberal democracies of any size in the modern world have moved away from being run as ‘unitary states’, with just one main centre of government plus a set of clearly subordinated local or regional authorities. For instance, some big European countries, like France, Italy and Spain, now have constitutionally protected regional governments, where before they were previously run as centralised Bonapartist states. Other liberal democracies are longstanding federal systems, notably Germany, the USA, Canada and Australia. So the UK’s rapid movement since 1997 towards creating more devolved government is something of a belated falling into line with other countries.

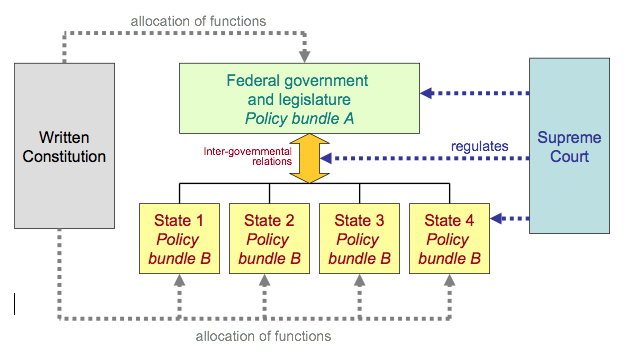

However, the UK follows a pattern of ‘organic’ devolution with varying powers decentralised to different countries and regions. This approach is very different from a federal state. Figure 1a shows that under federalism a written constitution (one that is normally fixed and quite hard to change) specifies just two ‘bundles’ of powers and competences. The first bundle is allocated to the federal or central tier, and the second bundle to the component states. All the states have the same powers here. The character of these allocations, along with the development of tax-raising powers and financial capacity at the two tiers, then create a system of inter-governmental relations. The federal centre may pick up new functions not specified in the constitution, and it may equalise financial capacities across states. It can also subsidise the states to do things on its behalf, or otherwise intervene. But it cannot change the constitution’s allocation of functions. So the federal tier can only realise policy objectives that clearly fall within bundle 2 by persuading or incentivising the states who ‘own those issues. In addition, a Supreme Court polices the activities of both tiers of government impartially, and impartially regulates inter-governmental relations.

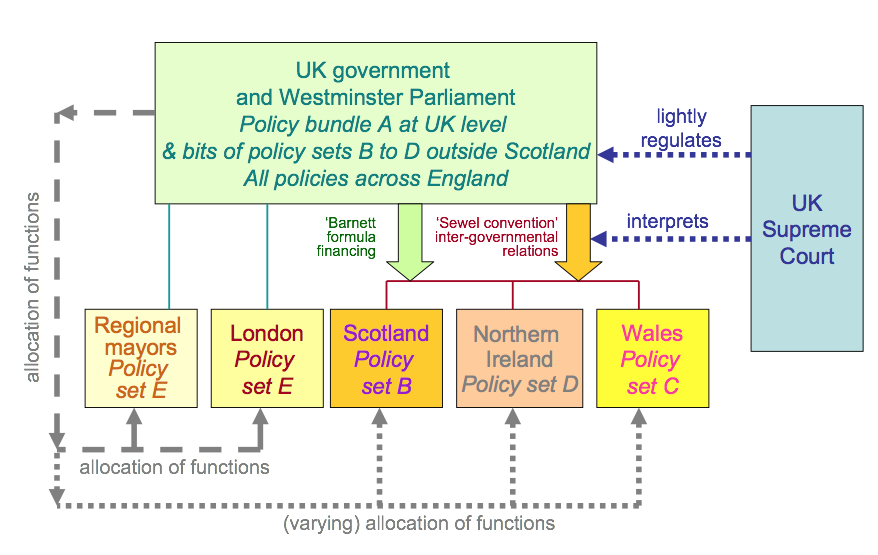

By contrast, in the UK there is no written constitution, and the foundational principle of ‘parliamentary sovereignty’ still implies that the Westminster Parliament ‘cannot bind itself’ legally. A set of major policies (especially defence, foreign affairs, and most tax-raising and welfare) are reserved to the UK centre. Different sets of policy functions have been devolved to national institutions in Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland in ways which politically are more binding, and may provide some constitutional protections to them. Yet as Mark Elliot has observed: ‘As a matter of strict law, the UK Parliament has merely authorised the devolved legislatures to make laws on certain matters, without relinquishing its own authority to make law on any matter it chooses — including devolved matters’. As we discuss below, Westminster actually still legislates changes that affect devolved policy areas, albeit so far with the consent of the devolved countries’ legislatures. So the extent to which devolved powers in Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland are protected constitutionally is obscure.

Figure 1a: How a federal government system works

Figure 1ab: The UK’s devolved government system

Within England extensive powers have been devolved to the executive Mayor and Assembly in London, and lesser sets of powers to executive mayors in some city regions. But here Westminster retains an (almost) untrammelled ability to alter who is responsible for any policy function within England.

There is also a very unsophisticated system of inter-governmental relations within the UK, with Westminster/England as the dominant player, accounting for five sixths (85%) of the population. There are only two key co-ordination mechanisms. First, most taxes are raised by the UK government, and it then allocates funding to the three devolved countries using a crude, fixed rule of thumb known as the ‘Barnett formula’. The three devolved countries get funding as a ratio of English spending, so if England cuts or raises public expenditure, the same happens to transfers from Westminster to fund devolved services.

Second, the UK centre has recognised a convention named after a peer Lord Sewel, which says that Westminster will not pass laws about the policy sets of Scotland, Wales or Northern Ireland without the consent of their legislatures and governments. What this means in practice is much debated (see below). The UK’s Supreme Court has some role in regulating inter-governmental relations between Westminster/Whitehall and the devolved governments. The Court is independent of Whitehall, and can in principle regulate how the centre behaves, but it has historically done so only in rather a light touch way, deferring to the need for a (national) government to operate effectively as it wishes.

Recent developments

In the 2014 Scottish Independence Referendum voters chose to remain in the UK by 55% to 45%, but only after the PM David Cameron had promised new powers for Scotland’s government. In Scotland and Wales the aftermath of this closely fought contest precipitated important changes in their constitutional arrangements. The Scotland Act 2016 and the Wales Act 2017 embodied the Sewel Convention in statute law for the first time, which was seen as a symbolic under-pinning for the permanence of the Scottish Parliament and the National Assembly for Wales.

Fiscal devolution to Scotland (important in the context of enhanced autonomy) featured prominently in the 2014 Smith Commission Report, and was the centre piece of the 2016 Act. It gave Edinburgh new powers over taxation – to set air passenger duty, to make an add-on to income tax rates and vary thresholds. On spending the Scottish government gained new social security powers on carers and disability welfare benefits, on topping up reserved benefits run by the UK, and on creating new ones.

The Wales Act 2017 also marks a significant reshape of the Welsh constitutional settlement with a move to a reserved power model, transfer of additional powers (i.e. energy, harbours) and more autonomy for the Assembly in dealing with its own affairs by devolving electoral franchise and powers over the size of the Assembly to Wales. However, the likely durability and robustness of the Act has been criticised heavily during the legislative scrutiny stage (see the National Assembly Constitutional and Legislative Affairs Committee Report on the Wales Bill 2015/16) and after receiving Royal Assent. Constitutional preferences amongst citizens in Wales point to strong support for greater autonomy. Given the choice between the Welsh National ‘Assembly to have more powers / Assembly to have same powers as now’, 73% of respondents to the regular BBC/ICM St David’s Day Poll in March 2017 chose more powers.

The devolution settlement in Northern Ireland has also seen some important changes. The size of the Assembly there was cut from 108 to 90 in 2016, and some of its powers (on welfare reform, and corporation tax) were altered.

The process of English devolution carried on in London with the already powerful executive mayor (and Greater London Authority) acquiring commissioning, strategic planning, funding and regulation powers in health and social care. Outside the capital new governance and leadership arrangements emerged piecemeal from 2014 onwards, initially in the absence of a clear legislative framework. The 2016 Cities and Local Government Devolution Act rectified this, and to date 11 devolution deals have been negotiated, not all of them implemented.

Some large-scope English deals cover areas such as transport and infrastructure, health, skills and employment, enterprise and growth, housing, planning fire services (as in Greater Manchester with a powerful executive Mayor). More modest deals bracketed as ‘devolutionary’, because Whitehall gives up some powers, range from combined authorities spanning city regions and led by an executive mayor (as in Liverpool City region) to combined authorities with a new elected Mayor with much fewer powers (as in Cambridge and Peterborough), down to a unitary council and local economic partnership model (Cornwall).

After the Brexit referendum

Voting on European Union membership in June 2016 revealed deep geographical divisions within the United Kingdom. Two devolved countries (Scotland and Northern Ireland) and the devolved city-region in London (with roughly the same population size as the other two combined) voted strongly to remain in the EU. Both most of the rest of England and Wales voted to leave.

The lead-up to the March 2017 triggering of formal ‘leave’ processes under the EU’s Article 50 was marked by visible tensions in intergovernmental relations between the UK central government and all three devolved country administrations. A Joint Ministerial Committee (JMC) of the three devolved countries and Whitehall ministers, which had previously been in abeyance, was resurrected by the May government to facilitate dialogue and consultation. It did not stop devolved administrations voicing their dissatisfaction with the low level of engagement and access that they had to the UK Government’s negotiating strategy.

In December 2016, the devolved administrations joined the legal challenge brought by Gina Miller against the May government, seeking to require them to seek Parliamentary approval before initiating the Article 50 ‘divorce’ process. The case went to the UK Supreme Court, and the devolved countries effectively forced a first legal test of the Sewel Convention, now reflected on the statute book in Scotland Act 2016 and Wales Act 2017.

The Supreme Court’s judgment took the view that ‘the UK Parliament is not seeking to convert the Sewel Convention into a rule which can be interpreted, let alone enforced, by the courts; rather, it is recognising the convention for what it is, namely a political convention, and is effectively declaring that it is a permanent feature of the relevant devolution settlement’ (page 48). This limited interpretation may none the less prove significant in the process of repatriating powers from the EU to either the UK government or the devolved governments (see below for more discussion).

| Current strengths | Current weaknesses |

|---|---|

| Devolution appears to be firmly entrenched in the national polities in Scotland, Wales, Northern Ireland, and in London. | The overall UK-wide devolution project lacks any constitutional coherence. It has evolved piecemeal, in asymmetric and specific fashion in each case, making public understanding harder. |

| Electoral systems used in the mainland devolved administrations (Scotland, Wales and London) secure broadly proportional representation. They arguably redress some of the representational defects inherent to Westminster’s plurality rule (FPTP) system. | Devolution deals in England have been negotiated in ways that lack transparency and have received little public scrutiny. |

| Some devolved legislatures have better records on gender representation than Westminster. There have never been under 40% women members in Wales, and never been under 30% in Scotland. Northern Ireland is still somewhat a laggard. | Turnouts in the new devolved mayor elections in England in May 2017 were low, reflecting citizen engagement in the devolution process there – although turnout in any new elections is often lower. |

| All the devolved legislatures and executives in Scotland, Wales, Northern Ireland and London were popularly endorsed in referenda before being implemented. The same is true of some English devolution schemes outside London. | The EVEL process does not ensure a ‘voice’ for England. It remains an opaque and complex parliamentary procedure, little known and understood by the general public. |

| Stronger levels of citizen engagement with national legislatures have become the norm in Scotland and Wales, whereas they remain the exception at Westminster. | Inter-governmental relations between the devolved countries and the UK are very poorly developed, and do not include London. Perhaps more significantly inter-parliamentary relations are vestigial. |

| Future opportunities | Future threats |

|---|---|

| The Brexit process looks likely to initiate another period of extensive constitutional flux. A positive consequence could be a window of opportunity to initiate an inclusive, nationwide deliberation about the constitutional future of the UK. So far, only a few Labour figures have called for such national conversation. | A potential downside of the Brexit process is that powers repatriated from the EU might accrue overwhelmingly in the hands of UK ministers and Whitehall, with little Parliamentary scrutiny. Perhaps the onward devolution of these powers to the three countries and to English regions and areas may be short-circuited or inadequate, resulting in a net centralisation of power. |

| Repatriating powers from the EU, in the spirit of subsidiarity, offers the opportunity of enhancing powers and competences of sub-national legislative assemblies. | Devolved administrations in Scotland, Northern Ireland and London have different Brexit aims from the May government and given the financial and political implications in the case of Wales and Northern Ireland. |

| As Wales moves from a conferred power model (where Westminster says what it could control) to a reserved power model (where powers rest with them permanently) so there may be a better constitutional alignment with devolution practice. | Further territorial divisions within the UK could be amplified by a second Scottish independence referendum. This possibility depends on the level of public support north of the border, but also on the perceived treatment of Scotland’s interests in negotiating the EU exit deal and the repatriation of powers. |

| The Mayoral elections in May 2017 were overshadowed by the general election called for a month later, and had rather low turnouts. But reruns in future will be opportunities to revitalise local democracy and to improve the visibility of devolution deals. | Any bullying UK-centric approach to repatriation of powers that seeks to overstep proper parliamentary scrutiny and involve devolved legislatures poses a serious threat to the principles of democratic devolution. |

| The level of dispute and contestation both in courts and politically may increase as a result of Brexit. | |

| The Conservative 2017 election manifesto unilaterally proposed scrapping the Supplementary Vote voting system used for elected mayors, in London and elected regions and replacing it with first past the post, which would radically lower mayor’s legitimacy. The manifesto is largely history now, but that such a non-consensus policy (also overturning local referenda) could have been envisaged by the Conservatives is an ominous sign for the future of English devolution. |

The further unfolding of Brexit

As the Brexit process enters a new stage of detailed ‘divorce’ negotiations with the European Union, a raft of new legislation will be needed to give effect to the multiple changes involved. It will cover areas such as agriculture, fisheries, transport, and economic and environmental regulation – all areas where the three devolved countries are primary actors within their own territories. As yet, however, there is little clarity on what role these devolved governments and legislatures will have in the passage of this legislation, at what stage they will intervene, and how the Sewell convention and ‘legislative consent’ process discussed below will operate. Early indications from the Legislating for Brexit: White Paper (2017) suggest that existing EU frameworks will in the first instance be replaced by UK common frameworks, moving powers back to the UK centre. Subsequently, ‘there will be an opportunity to determine the level best placed to take decisions […] ensuring power sits closer to the people of the UK than ever before’ (paragraph 4.5).

If the spirit here follows a subsidiarity principle in a full-hearted way, then devolved administrations and legislatures would see their functions and responsibilities greatly enhanced, and could play an enhanced role in the process. However, there is no single mention of the notion of ‘legislative consent’ by the three devolved countries in the White Paper, nor any indication of inputs to be made by the devolved legislatures. Thus the May government, before the disastrous 2017 general election, seemingly envisaged a highly executive driven process. Their approach centred on ministers and Whitehall negotiating with the devolved administrations, thus relying on one of the weakest links in the devolution settlement so far, namely the current poorly institutionalised inter-governmental relations.

The Sewel convention and legislative consent

If a Westminster MP seeks to ask a question of UK ministers about a matter that forms part of the devolved powers of the Scotland, Wales or Northern Ireland governments and Parliament/Assemblies the Speaker of the House of Commons will immediately intervene to rule the question out of order. So an outsider might have expected that Westminster would simply have stopped legislating about issues that are now controlled by devolved legislatures.

In fact that has not happened. Looking for a moment just at the UK-Scotland case, on about ten occasions a year, every year for 16 years now, the Westminster Parliament has legislated in ways that change the powers of the Scottish government and the Edinburgh Parliament. But in each case they have done so after a Legislative Consent Motion (LCM) was framed by the Scottish government and accepted by the Edinburgh Parliament. In almost all cases the effect of the legislation has either increased or left intact but varied in some way the powers of the Scottish government. And these changes have been accepted because they improve policy-making north of the border, maintain consistency across the two parts of the UK, and can conveniently be ‘piggy-backed on England and Wales legislation going through the Commons.

The Sewel convention is an agreement that ‘Westminster would not normally legislate with regard to devolved matters in Scotland without the consent of the Scottish parliament’. Initially rather informally established (like all other conventions), this was later formalised. A section of the Scotland Act 2016 clearly stated: ‘It is recognised that the parliament of the United Kingdom will not normally legislate with regard to devolved matters without the consent of the Scottish Parliament’. It also applies to Wales now in the same form.

However, the UK Government’s Devolution Guidance Note 10 interprets the Sewel Convention very restrictively as follows:

‘[W]hether consent is needed depends on the purpose of the legislation. Consent need only be obtained for legislative provisions which are specifically for devolved purposes, although Departments should consult the Scottish Executive on changes in devolved areas of law which are incidental to or consequential on provisions made for reserved purposes’ (paragraph 2).

The difference between these two views is quite wide legally. For example, Mark Elliot has argued that if the Westminster government wanted to withdraw the whole UK state from the European Human Rights Convention (as the Conservatives in 2015-17 long said they wished to do), then it could so – because the action does not relate solely to devolved powers (as Brexit does not). However, what Westminster could not do within the Sewel Convention was then to put in place a ‘British Bill of Rights’ (as the Conservatives at one stage planned to do) – because this would vary the powers of the devolved country administrations and require their legislative consent.

It thus remains pretty unclear whether the repatriation of powers from the EU to the UK falls foul of the Sewel convention, which would give Edinburgh and perhaps Northern Ireland a lock on the process because it automatically varies their powers without their consent. As we noted above, the Supreme Court refused to see this as legally necessary, regarding Sewel as a purely political convention. A neatly separated, two-stage movement of powers – back from Brussels to London, and then down from London to the devolved countries – seems to be what Tory ministers envisage. But even some of them have hinted that legislative consent from Edinburgh would be needed for the first stage as well.

Conclusions

Devolution in Scotland, Wales, Northern Ireland and London has strengthened representation, legitimacy and the inclusiveness of policy debates there. Devolution in England outside London has just begun, but might be expected to redress important democratic, deliberative and scrutiny deficits there as well. However, both types of devolution still lack clarity and coherence, with poor inter-institutional relations and questionable constitutional and legal protections for even devolved powers in Scotland (the most powerful devolved country). As a result, the overall durability of democratic devolution in the UK seems still unsettled.

This post does not represent the views of the LSE.

Diana Stirbu is a Senior Lecturer at London Metropolitan University.

Patrick Dunleavy is Professor of Political Science and Public Policy at the LSE.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

It is surely inaccurate to suggest that “extensive powers have been devolved to the Mayor and Assembly in London”. The use of such a phrase suggests a misreading of the legislation which introduced the London Mayor. The London Assembly has no powers, and as a former Assembly Member I can confirm that we were barred even from access to any important documents or information relating to London and its governance on the basis of “commercial confidentiality” and therefore had to rely on the slow and cumbersome process of applying for information under the Freedom of Information provisions! All the time frustrated by the Mayor and his staff. How to ‘hold the Mayor to account’ (the main reason for the Assembly’s existence) six months after the issue has come and gone…

What was fascinating was that when the last Labour government ‘reviewed’ the powers of the Assembly, it actually took away any meaningful ones that had emerged by accident in small areas, something that my group predicted and went on record about – for example in the Assembly’s role on the fire authority (LFEPA) it squashed the ability to challenge the Mayor. The aim of government was simple – a centralised authority with one person beholden to central government (the Mayor) whose strings can be jerked by virtue of the fact that most of the cash comes from government…seriously annoy the government of the day…and you suddenly get told that economies mean less cash…and you and your party are going to the polls asking for more cash from the voters.

And where, in any event, did much of these powers come from in this humpty dumpty ‘devolution’? Yep, the powers were ‘devolved’ upwards, from authorities and boroughs operating at local level (that meaningless and non-binding ‘subsidiarity’ we talk about worked well there then! powers made more remote in the name of devolution).

This ‘devolution’ is nothing of the sort – it is the creation of an easy one-person target for greater centralisation by central government as opposed to controlling a gaggle of inconvenient and varied smaller authorities.

The interesting point here is that departure from the EU might make a difference and will allow the circumstance for greater and more real devolution – at the moment you cannot have devolution because the lawmaking powers in crucial areas have again been ‘devolved’ upwards – UK bodies whoever they are act simply as gauleiters for the EU centre. The future could be very different out of the EU.