Audit 2017: How democratic is the protection of workers’ rights within the UK?

During the 20th century, developed societies increasingly accepted that democracy could not stop at politics, and had to extend to aspects of the economy as well. Democracy in the economy began – and continues – with workers’ rights. As part of the 2017 Audit of UK Democracy, Ewan McGaughey and the Democratic Audit team explore how far they have been handled democratically and effectively in the UK.

A poster in Euston, London highlights the low pay of food delivery workers. Photo: russell davies via a CC-BY-NC 2.0 licence

This article was published as part of our 2017 Audit of UK democracy. We have now published: The UK’s Changing Democracy: The 2018 Democratic Audit with LSE Press, available in all ebook formats. You can download the whole book for free, and individual chapters, including a fully revised version of this article.

The labour movement across every democratic society has always demanded rights that transcend the market. People at work lack bargaining power. As Adam Smith told us, employers can ‘hold out’ longer in any negotiation because wealth is unequally distributed. In a democratic society, the goal of labour law has always been to have universal rights that are not up for sale.

What does democracy require for the protection of workers’ rights?

- A minimum floor of workplace rights, that nobody falls through, to ensure everyone has the basic income, time off work, and dignity that they need to pursue the true values of human life: science, philosophy, art, music, sport, nature, family and participation in community life.

- Fair pay through a voice at work, above the minimum floor, by collective bargaining through free trade unions and votes in workplace governance, to guarantee productivity, innovation and prosperity.

- Equality and social inclusion, in all work relations, based on the content of one’s character, skills, qualifications and conduct. There must be no discrimination for unjustified factors: race, gender, orientation, age, belief, union membership, agency, part-time, fixed-term or any other irrelevant status.

- Job security. This means stopping conflicted or irrational employer dismissals, so that: (a) Workers must get reasonable notice of termination. (2) Dismissal can take place only on fair terms, judged by one’s peers and the law of the land. And (3) severance pay exists to halt socially unjustified redundancy.

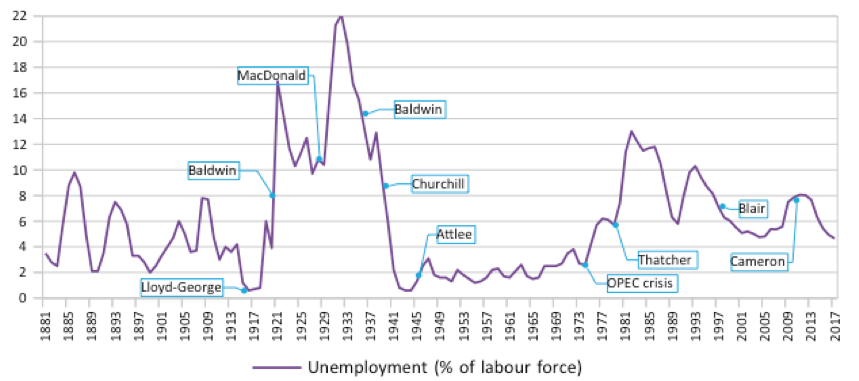

- Full employment (around 2%) would be central to every government’s fiscal, monetary and trade policy. Chart 1 below shows this between 1945 and 1973.

Chart 1: UK unemployment 1881-2017, with major government changes.

Sources: Denman and McDonald (Jan 1996), and ONS, MGSX (1995-2017).

Recent developments

Since a Conservative-led government took power in 2010 a long series of changes to labour law took place. The combined effect is that British people have seen the longest sustained wage decrease in modern British history, unseen since the eras of revolution and plague. Statistical calculations of this decline show average changes: for the people below the average, the picture is worse. In democratic terms, it is significant that almost all major changes to workers’ rights were made using executive fiat, bypassing Parliament.

The government withered most minimum rights by stopping their enforcement, either in court, or by public bodies under government control in four ways. First, a 2013 Order introduced Employment Tribunal fees of £1200 for the typical claimant. This deterred almost 80 per cent of claimants at these tribunals. In July 2017 the UK Supreme Court considered the introduction of tribunal fees and declared them unlawful, forcing the government to pay back £32m in fees, but providing no redress for people who had not launched Tribunal cases because of the fee burden. Second, even when people can afford Tribunal fees, the statutory right to claim unfair dismissal (that is central to most claims) was cut by a 2012 Order. People now have to work for two years, instead of one, to qualify for this right. Third, in 2014, the government stated a policy that Jobseeker’s Allowance would be refused if people turned down ‘zero hours’ contracts. These contracts mean an employer purports to have an arbitrary, unilateral power to vary working hours down to zero. Used like this, zero hours contracts have been found in court to be an unlawful sham. They violate the common law duty to fulfil the reasonable expectation of stable work.

Fourth, under Treasury orders, Her Majesty’s Revenue and Customs has not enforced income tax, National Insurance or minimum wage duties against ‘gig economy’ corporations. One exception (proving the rule) has been Deliveroo. But Uber, CitySprint, Mechanical Turk, and more have been left alone to engage in mass tax fraud. It is fraud because their lawyers know the workforce has employment rights (see below). They deliberately wait for someone to sue before they pay.

Fifth, the government delayed all sorts of laws being brought into force, or did not activate them at all. In the Pensions Act 2008, the right to automatic enrolment in a basic pensions was delayed between 2 and 10 years – that is, for many people the right to an occupational pension was destroyed for a fifth of their working lives. Under the Work and Families Act 2006, the right of parents to share child care leave with one another was delayed until 2011. Last, but not least, Theresa May as Home Secretary halted virtually all investigations by the Gangmasters Licensing Authority into migrant and agricultural worker exploitation. She also scrapped the Equality Act 2010 duty on public bodies to promote socio-economic equality. It was, she said, ‘ridiculous’.

The methods used to frack the floor of minimum rights bypassed representative democracy with ‘Henry VIII clauses’. Increasingly, Acts of Parliament are passed with the ability of any Secretary of State to amend legislation at will. Social rights are being treated like an on-off switch, to be varied at the executive’s whim. The minimum wage itself has been cut like this for people aged under 25. This is the most vulnerable worker age group because they are most likely to be on zero hour contracts, or in precarious work. The economic theory the government uses to justify it seems to be that if employers can make young people unemployed more easily, there will be less youth unemployment. This Milton Friedman theory has no basis in evidence, and has been maintained solely by ideology. Parliament did use primary legislation, the Enterprise and Regulatory Reform Act 2013 section 78, to abolish the Agricultural Wages Board of England and Wales. This Board maintained a higher scale of minimum wages, based on experience, for people doing hard manual labour on farms. When the Welsh Assembly decided to keep a Board for Wales, the Attorney General brought court action. The government lost in the UK Supreme Court.

There has been progress for people over 25, in that the minimum-living wage rose since 2010, and was promised to be £9 an hour by 2020. But people do not want the minimum-living wage. They do not just want a ‘basic’ income. People want a fair day’s wage for a fair day’s work. Most people have no voice at work. They get told what their pay and conditions will be. They are told to ‘take it or leave it’. When people protest about reductions in pay, their corporate managers say, ‘you’re fired.’

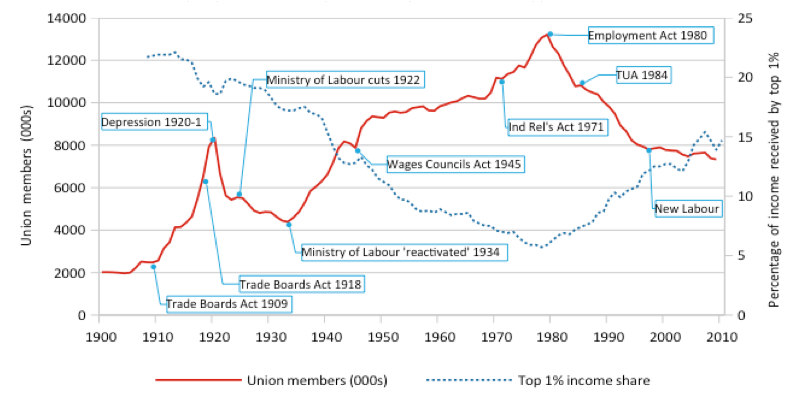

Chart 1 shows the consequences of labour rights for union membership and inequality. Union membership continued to wither while Boris Johnson called for more anti-union laws in 2010, Vince Cable released the Employer’s Charter in 2011, and Eric Pickles demanded an end to union time-off in 2012. In 1979, collective agreements covered 82 per cent of the British workforce, and now the figure is around 20 per cent. Correlation is not always causation. But in the UK, the relationship is clear. The loss of voice at work made inequality soar.

Chart 2: UK trade union membership, and income inequality.

Sources: Piketty (2014) Table S9.2, and Brownlie (2012) DBIS.

Three main changes were made to collective labour rights since 2010. First, as an employer itself, the government has simply refused to engage in meaningful collective bargaining. Instead, from 2010, it froze public sector pay, cut pensions, and made mass-redundancies: all to shrink (without any particular principle) the size of the state. This has been seen from the civil service, to the London Underground, to the NHS and the emergency services.

Second, the government fought human rights challenges to its statutory ban on solidarity action by trade unions, threatening to leave the European Convention on Human Rights. In RMT v United Kingdom [2014] ECHR 366, the Strasbourg Court caved. It held that the right to freedom of association in article 11 of the Convention did not protect the right of workers in a subsidiary company to strike against the parent company, or vice versa. The UK was ‘at the most restrictive end of a spectrum of national regulatory approaches on this point’ (along with Turkey, Russia, etc). The reasoning was thin. With the Tory threat of leaving the Convention, the judges found the law within the UK’s ‘margin of appreciation’.

Third, after a majority Cameron government returned in 2015, the Trade Union Act 2016 was passed. This introduced a requirement for a 50% turnout in strike ballots, and a 40% total support rate (80% turnout in close votes) if strikes were to be legal in health, school education, fire, transport, nuclear waste, and border services. The Act maintains a ban on electronic voting in union ballots. A review will be conducted by a retired fire chief to decide if postal voting is adequate in the 21st century. The Act requires that at each picket, a union supervisor holds an ‘approval letter’ from the union, and ‘must wear something that readily identifies’ them. It wraps collective action in more red tape and pointless form-filling obligations, all designed to slow collective action and weaken bargaining power.

Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities and Threats (SWOT) analysis

| Current strengths | Current weaknesses |

|---|---|

| Compared to the United States, Eastern Europe, China or other quasi- and non-democratic jurisdictions, the UK has a relatively sound system of minimal labour rights. In the past the UK worked inside the European Union to ensure that many rights apply continent-wide. | Compared to Sweden, Denmark, Norway, Germany, France, the Netherlands, or other Western European countries, Australia, Canada, New Zealand or other developed Commonwealth countries, the UK has serious deficiencies in every respect in its labour rights. It systematically fails core labour standards of the International Labour Organisation, ratified by and binding on the UK in international law. |

| A national minimum wage covers most people in law. There are 28 days of paid holidays a year, and health and safety at work has improved with the transition towards a service economy. | The UK has failed to sustain a policy of full employment since it accepted that some joblessness was ‘natural’ after the 1974 OPEC crisis. Since then, unemployment has ranged between 4.3 and 11.9 per cent. This has led to millions of hardened lives, in poverty and precarity, and squandered trillions of pounds in lost prosperity. |

| Almost everyone has the right to not be discriminated against on grounds of their race, gender, sexual orientation, religion or belief, age, union membership, part-time, fixed-term or (after 12 weeks) agency status. | The UK fails to guarantee votes at work through enterprise governance and sectoral collective bargaining. It is in a minority of EU countries with no workers’ voice in the governance of firms (outside universities). |

| There are clear rights to join a union; for unions to be recognised for collective bargaining with majority support in an enterprise; and for unions to take collective action for the defence of workers’ interests. | UK laws, as Tony Blair said in 1997, are ‘the most restrictive on trade unions in the Western world’. This has destroyed the ability of people to achieve fair wages, beyond the minimum, in their sector. |

| On job security, before any dismissal UK employees have the right to one week’s notice after one month’s work (and two weeks after two years, three after three, up to 12). After two years there is a statutory right to be dismissed only for a good reason, and a severance payment for redundancy. | The UK fails to ensure enforcement and universality of core labour rights, particularly on dismissal protection, child care rights and the state pension. The pursuit of ‘flexible’ labour markets has shot the welfare state with holes, damaging growth, increasing stress and depriving people’s dignity in childhood, in their working lives and retirement. |

| Despite the Equality Act 2010, the UK has state-sponsored sex discrimination in child care leave: there is very low paid maternity leave, and virtually nothing for paternity. Any segregation in law, or an ability to transfer rights, perpetuates the gender pay gap. It stacks the odds against women’s careers, and harms fathers’ relationships with their children. | |

| Dismissal law lets employers act on conflicts of interest, and make irrational decisions, fuelling recessions and damaging sustainable enterprise. The UK has not yet made legislation for elected work councils to defer flawed decisions to dismiss colleagues. |

The gig economy, robots and precarity

New technologies raise no new issues for labour policy: the difference today is failure to deal with aggressive management practice of emerging tech firms, and evasion of labour rights and tax. In the ‘gig-economy’ the typical work and payment method is ‘piece-work’, not a yearly salary or hourly pay. People are paid for individual taxi rides, food deliveries, bits of programming, and so on, as if they were self-employed. A gig firm purports to be a neutral agency, linking worker and consumer, but not in an employment or consumer relationship, to evade tax and rights. In most cases, this qualifies as civil law fraud. It is objectively dishonest by the standards of reasonable and honest people. This does not mean the predatory business in the gig-economy is new, but simply that existing law seems not to be being enforced in these areas.

For example, Uber knows that the Californian Labor Commission has ruled its drivers are employees. It knows that the same position probably holds true in almost every jurisdiction. It knows the majority of legal opinion states that it is an employer. But just as it ran as an illegal, unregistered taxi company until it was banned in Germany, it will refuse to abide by the law and pay tax until it is made to. This qualifies as civil dishonesty, under the Fraud Act 2006 section 2. It does not matter that HMRC, under a Conservative administration, has failed to act itself. In the UK, it is possible for HMRC to change its position immediately. The government has simply not let it do so. The ‘Taylor Review’ was unable to alter this, but in any case appears to have sided with multinational corporations, and failed flexibility theory, over human rights and social prosperity. Fortunately, reviews are not law.

Technological change is also predicted by some pop-writers to mandate mass redundancies in future: from driverless cars to financial advice or journalism. One piece of now ‘viral’ academia from two theorists speculated that 47% of all US jobs are ‘potentially’ at risk ‘over some unspecified number of years’. By contrast, a report from Obama’s White House suggested this was a wild exaggeration. Even if so many jobs were at risk, and the losses were concentrated into a few years, the social problem would be considerably smaller in scale and kind compared, for instance, to demobilisation after World War Two. The true problem is not only a fraction of that size, but also of considerably less social complexity. Automation will not create, for instance, massive numbers of disabled or dead people. The only important question is whether ownership of patented technology, and capital goods, is sufficiently distributed through the shareholding system in corporate governance – particularly through pensions – to guarantee everyone shares in the gains of growth. For this, collective bargaining, votes at work, votes in the economy, and an active democratic state, are crucial.

Free movement and immigration

As globalisation intensifies, and especially before every society reaches comparable levels of human development, the quantity of migration may increase. The UK has swung from being the most open country since 1997, to attempting to be one of the most closed since 2010. Current political debate has some echoes surrounding the reverse of the British Nationality Act 1948, changed by the Commonwealth Immigrants Act 1962 and Enoch Powell’s ‘rivers of blood’ speech in 1968, against citizens of Commonwealth countries. With the EU the UK and Ireland were the countries most open to the ten new member states in 2002. Britain declined to apply transitional restrictions on free movement, but changed its stance when Romania and Bulgaria joined in 2007. The Conservative government agreed to take only 20,000 refugees by 2020 from the civil war in Syria (of which 2011 have been admitted to date), even though the war and the ‘Islamic State’ partly result from the US/UK invasion of Iraq in 2003. The missing element of immigration policy is any serious commitment to international, regional and full employment. People move because of wars, persecution, economic necessity, and sometimes out of choice. Truly ‘free’ movement is much rarer than ‘unfree movement’.

Workers’ rights and Brexit

The referendum on EU membership in 2016, and the snap general election destroying the Conservative government majority in 2017, pose an existential threat to all workers’ rights, including those deriving from EU law. When the EU has agreed new Directives or Regulations that create worker rights, the UK has put some into primary Acts of Parliament. Many were already in UK law. But other rights were put into secondary legislation. The European Communities Act 1972 section 2(1) empowers the Secretary of State to make Regulations to comply with standards we make through the EU. These include,

- Working Time Regulations 1998 (28 paid holidays, rest breaks and limits on working week)

- Part-time Workers (Prevention of Less Favourable Treatment) Regulations 2000

- Fixed-term Employees (Prevention of Less Favourable Treatment) Regulations 2002

- Agency Workers Regulations 2010

- Information and Consultation of Employees Regulations 2004

- Transfer of Undertakings (Protection of Employment) Regulations 2006

Any workers’ rights that are not contained in primary legislation (an Act) could be repealed at will by a Secretary of State if the UK leaves the EU in a ‘hard Brexit’. In any Brexit, workers also lose the right to vote in the standards that apply across border. Like the UK itself, they consequently lose bargaining power in a global economy. This does not mean workers’ rights will be repealed. But while any major political party is ideologically hostile to labour nothing is safe.

This Brexit vulnerability does not mean that EU law has been all good for workers’ rights. The extent of EU law’s impact on the UK is disputed. The four core EU freedoms (movement of people, capital, services and establishment, or goods) exacerbate underlying inequality of bargaining power, if labour rights and public services are not supported everywhere. The Court of Justice of the EU in three major cases (Viking, Laval, Rüffert) said trade unions’ collective action, and pro-labour government procurement policy, might have to be used proportionately to (ostensible) business freedoms. Its theories of ‘market access’ have largely derived from arguments developed by British academics and lawyers (particularly in Viking). The result has been marginal limits on cross-border union action, workers posted in from other EU countries being used to undercut domestic collective agreements, and some governments abandoning procurement policy that ban contractors paying their workers ‘poverty’ wages.

Within the EU, the Court’s interpretations have been resisted by all European trade unions and social democratic parties, so that regressive policies are being changed or circumvented. In this way, ‘social Europe’ is currently more resilient than ‘social Britain’. However, the European Central Bank and Commission have pursued a massive assault on collective labour rights, minimum wages, public sector employment, and job security in its debt collection agreements with Greece, Portugal, Spain and Ireland. Again, however, the political consensus has turned against austerity, because of overwhelming evidence that it has failed.

Because Brexit is a European problem, and the causes of Brexit are shared across Europe and the globe (falling incomes, failure of development policy, deficient democratic structures) any solution must be an international one. Securing a fair day’s wage, for a fair day’s work, for all would mean reversing escalating inequality through voice at work; reversing regional decline through credible public investment; ending financial oligarchy with transparency and corporate governance reform; and restoring dignity and hope through returning to full employment policies.

Democratising enterprise governance

A critical issue in 21st century society will be how votes in the economy become democratised. The UK is in the minority of EU countries (generally the poorer ones) without general rights of workers to vote for representatives on company boards. Out of 28 EU member states, 16 have worker participation laws across private and public sectors. The UK is behind, even though it probably had the first laws in the world, and maintains votes at work (without transparency, highly imperfect, but still there) in its most globally successful enterprises: universities.

On the capital side, asset managers take almost all the votes on company shares, even though these are bought with other people’s retirement savings: in pensions, life insurance and mutual funds. Unions and employee elected pension trustees are beginning to demand that their shareholder voting rights are only exercised according to their instructions. Discussion has begun about the legitimacy of asset managers and banks voting at all in company AGMs. In private enterprise, a new democratic constitution for the economy will ensure that workers have votes in their companies, that all votes on capital are exercised by the true investors, and that the public and consumer interest is far better represented in network and natural monopolies than presently.

Conclusion

Workers’ rights are at a critical juncture in the UK in 2017, reflecting major challenges faced by trade unions (and allied social democratic parties) worldwide. The globalisation consensus around ‘flexible’ labour markets, major reductions of job security, only restrictive collective bargaining in individual enterprises, and hostility to workers having any voice in corporate governance has begun to crack. Empirical evidence has mounted that hostility to labour rights and economic democracy on the basis that markets will solve every problem has been a deeply self-harming belief. Law makes markets exist or fail. Workers’ rights are the first step towards making markets work for society, not the other way round.

This post does not represent the views of the LSE.

Ewan McGaughey (@ewanmcg) is a Lecturer in Private Law at Kings College London.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.