Money is key for democratic politics but its abuse is often clearly perceived as a problem by citizens

The maintenance of democracy requires the balancing of various demands, among them economic liberty and democracy. Here, Ferran Martinez i Coma shares research which looks at the way these two demands interplay in campaign finance, with the Electoral Integrity Project producing research which shows the extent to which this and related issues affect citizen confidence in democratic systems worldwide.

Lula (Credit: thierry ehrmann, CC BY 2.0)

A few weeks ago the former Brazilian President, Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva (Lula) was detained, questioned for about four hours and released. Authorities were looking into the $8.12 million in donations that Instituto Lula – his nonprofit foundation – had received by construction firms. Such firms had very important relationship with Petrobras, the biggest Brazilian corporation. According to the prosecutors, those 8.12 million are just a tiny fraction over the $2 billion in the operation Lava Jato. The Secretary of Finance of Lula’s Workers’ Party (PT), João Vaccari Neto, has been sentenced to 15 years in prison for receiving “irregular donations”. This is not the first time in Brazil that finance and politics have a problematic, to say the least, relationship as the Mensalao case attests.

Unfortunately, scandals over money and politics seem to be a constant, rather than an exception as many countries have experienced scandals. To mention a few cases, in the United Kingdom, Peter Cruddas, the Conservative Party treasurer, appeared to offer access to the Prime Minister for £250,000 pounds. Other recent examples include Kenya, with the Anglo Leasing case; in Spain, where all the treasurers of the government party, the conservative Popular Party (PP) have been charged with corruption; and Australia, where members of the New South Wales parliament have been charged with accepting illegal donations. Neither is Asia risk-free, as in recent years there have been problems, to mention a few, in Indonesia, Japan or South Korea.

But just how widespread are these problems?

New evidence on this topic has been gathered by the Electoral Integrity Project. The annual report compares the risks of flawed and failed elections, and how far countries around the world meet international standards. The report evaluates the integrity of all 180 national parliamentary and presidential contests held between 1 July 2012 to 31 December 2015 in 139 countries worldwide, including 54 national elections held last year.

The report highlights the way that campaign finance has consistently been ranked as the worst stage of the electoral cycle since PEI started. Regulating political finance is a challenge facing many countries around the world, and scandals over the role of money in politics make the headlines practically every day.

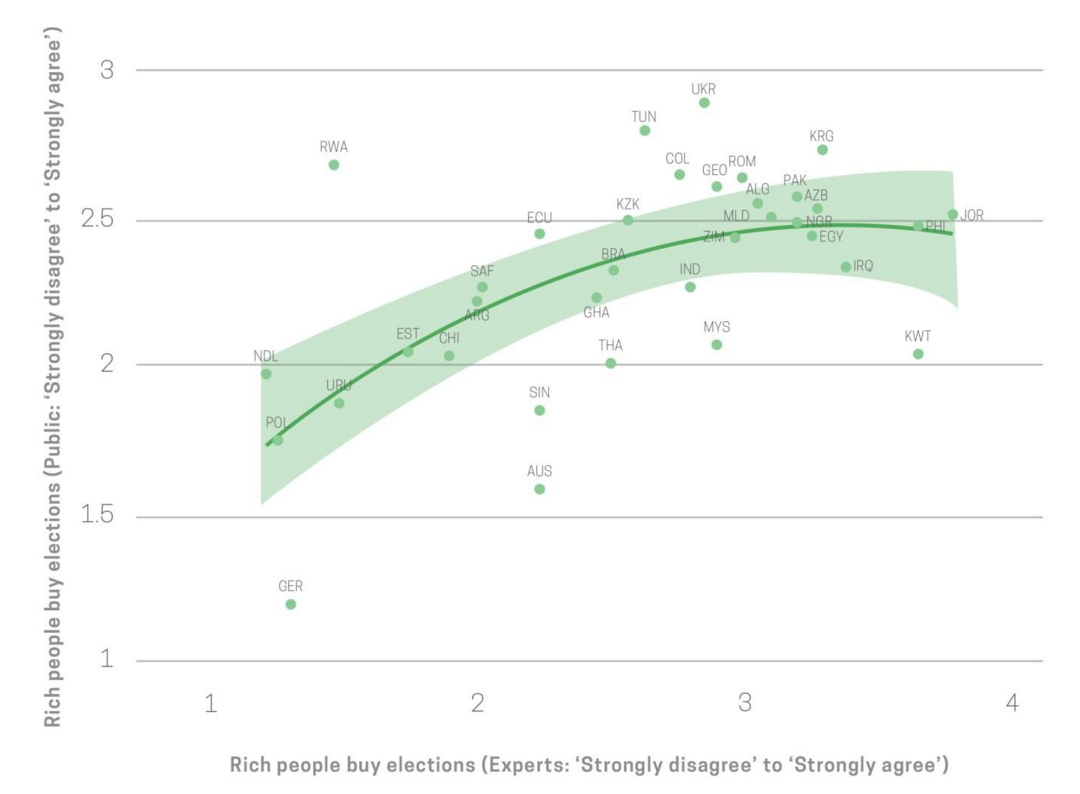

These are not just hidden problems: the public is also aware of scandals regarding money in politics. To compare public opinion, we can use information from the 6th wave World Values Survey (WVS-6). Both experts and the general public were asked how far they agreed or disagreed with the statement that “rich people buy elections”. The correlation between mean assessment by the mass and elite in each country is moderately strong. Observations below the 45-degree line, imply that the experts are more critical than the public while the observations above imply that the public is more critical than the public. The Figure illustrates that the experts are often more critical than the public, although the relationship is quite consistent.

Figure: ‘rich people buy elections’ – agree or disagree?

Source: The Perceptions of Electoral Integrity (PEI-4.0) expert survey, release 4.0; World Values Survey (WVS), 6th wave

Overall, money is key for politics, but its abuse is often clearly perceived as a problem. Beyond specific scandals, some other factors may possibly drive these perceptions. One concerns the type of campaign finance regulation –such as the use of public subsidies, spending limits, donor caps and transparency requirements. Do we observe common regulatory frameworks in those countries that perform better (or worse)?

Furthermore, beyond the legal and regulatory provisions, we know little about the cultural norms surrounding clientelism and patronage politics, the acceptability of vote-buying practices, and the political use of bribery. This is important, as laws do not always lead to their expected results. The level of corruption and economic inequality in a society are other explanations to consider when exploring how money in politics drives the integrity of elections.

To address these critical problems, the Electoral Integrity Project worked with Global Integrity and the Sunlight Foundation in a project on Money, Politics and Transparency, designed to generate research that can help to build more effective political financing regulations in any country. The research focused on the challenges of regulating political finance around the world, including why it matters, why this regulation succeeds or fails, and what can be done to address these problems. EIP brought together a wide range of international scholars and practitioners with expertise in the area of political finance, producing a short executive report (July 2015) and, with Oxford University Press, an edited book titled Checkbook Elections: Political Finance in Comparative Perspective (New York, May 2016).

—

This post represents the views of the author and not those of Democratic Audit or the LSE. Please read our comments policy before posting.

—

Dr Ferran Martínez i Coma is a Research Associate at the Electoral Integrity Project at the University of Sydney. Prior to this position, he was a Technical Adviser for elections for the General Direction of Interior Policy of the Ministry of Internal Affairs, in Madrid, Spain. His academic profile can be found here.

Dr Ferran Martínez i Coma is a Research Associate at the Electoral Integrity Project at the University of Sydney. Prior to this position, he was a Technical Adviser for elections for the General Direction of Interior Policy of the Ministry of Internal Affairs, in Madrid, Spain. His academic profile can be found here.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

A look into how citizens perceive #PoliticalFinance around the globe. via @democraticaudit https://t.co/sR9OdZLR3b https://t.co/XoyXcaCtmE

Money is key for democratic politics but its abuse is often clearly perceived as a problem by citizens https://t.co/yRqv3MQrto

Money, politics, liberty, democracy – useful piece from our friends @ElectIntegrity https://t.co/b0yeCjVjie @SunFoundation @MPTransparency

Money is key for democratic politics but its abuse is often clearly perceived as a problem by citizens https://t.co/5y61IxoBFG

Money is key for democratic politics but its abuse is often clearly perceived as a problem by citizens https://t.co/RzAOhSiMZN

RT @PJDunleavy: Money is key for democratic politics but its abuse is often clearly perceived as a problem by citizens https://t.co/ZVKpYZN…

W/ @ElectIntegrity & #WVS data: “money is key for politics, but its abuse is often clearly perceived as a problem” https://t.co/OcvMwfrZ3J

Money is key for democratic politics, but its abuse is often clearly perceived as a problem by citizens https://t.co/OYy91ZPpYB

Money is key for democratic politics but its abuse is often clearly perceived as a problem by citizens https://t.co/3mezpeP6ZX

Money is key for democratic politics but its abuse is often clearly perceived as a problem by citizens https://t.co/3eep0C105T

Money is key for democratic politics but its abuse is often clearly perceived as a problem: https://t.co/4tN9kG2sbY

@democraticaudit

During a global economic crisis “effective democratic participation” is stretched to the limit and beyond. (ref: above article)

Individual citizen resources required to uphold “quality of living” on the national territories affected are being squeezed across-the-board.

For example, the United Kingdom 8-year Austerity Programme 2010-2017 is a strategy designed to operate an economy at a “minimal funding” levels for a interim period… this places “stresses” on individuals which would be unsustainable over the long-term.

These stresses are currently insufficiently acknowledged, with regard to the need to uphold custodianship of individual political citizen responsibilities year-by-year.

As a result, the “one citizen, one vote” democratic principle is operating in practice at on-going levels of elevated risk.

Money is key for democratic politics but its abuse is often clearly perceived as a problem by citizens https://t.co/ZVKpYZNkG1

Money is key for democratic politics but its abuse is often clearly perceived as a problem… https://t.co/srwab8KxcD https://t.co/AOuedyA8Mf