Elections and Covid-19: making democracy work in uncertain times

Erik Asplund and Toby James discuss the dilemmas countries around the globe face about holding or postponing elections during the pandemic, and set out some guidelines to follow in ensuring democratic participation remains fair and open during the crisis.

Photo by Tedward Quinn on Unsplash

One of the defining characteristics of a democracy is that it holds regular, periodic elections. This requirement was famously enshrined into the Article 21(3) of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. The certainty of holding an election means that citizens are given the opportunity to remove or extend the mandate for their representatives and leaders.

At the same time, there are occasions where a natural disaster, famine or epidemic may mean that holding an election will potentially introduce considerable threats to human life. The problem has been laid bare with the pandemic coronavirus disease (Covid-19). From citizens queuing to vote at polling stations to public officials counting votes in crowded halls, elections have suddenly become opportunities for the spread of the infectious disease, as much as democratic rituals.

As a result, during March 2020 only, more than 12 national and 20 subnational elections originally scheduled for March–May have been postponed by 30 countries around the globe. Further postponements are likely given the rapid spread of the virus. Meanwhile, some countries have indicated that national elections will go ahead as originally planned. This includes parliamentary elections in Mali (first round scheduled on 29 March), which have already been postponed several times since 2018 due to security challenges. Parliamentary elections in South Korea (15 April) and presidential elections in Poland (10 May) are still on schedule too.

Why are some countries pausing and others not during the Covid-19 pandemic? The decisions about whether to continue or cancel are not straightforward, and the conclusions of policy-makers’ deliberations are not always closely linked to the confirmed number of cases of infected people, or whether countries are democracies that remain strong or those experiencing democratic backsliding (according to global state of democracy indices). Unlike Mali, which has 2 reported cases (as of 26 March), both South Korea (9,241 cases as of 26 March) and Poland (1,080 cases as of 26 March) have had many reported cases. Democracies have both continued (Germany) and postponed (United Kingdom) elections, and so have states that have seen democratic backsliding (compare Russia and Poland).

Debates echo around the globe. The spirit of Abraham Lincoln in 1864 has been cited ahead of the US Presidential election. ‘We voted in the middle of a Civil War…We voted in the middle of World War I and II. And so, the idea of postponing the electoral process is just – seems to me, out of the question’, Joe Biden has reportedly said. Elsewhere, however, French President Emmanuel Macron has repeatedly said ‘we are at war’ against the coronavirus, as he announced that the second round of local elections due to be held on 22 March would be postponed. Researchers noted that the health of both voters and election officials could be put at risk. Many poll workers are often older, retired volunteers, studies show.

Undermining democracy?

Postponements might at first glance undermine our experience of democracy. If people can’t vote when they would have been able to, there could be a sense of loss of voice. The term of office for incumbent legislators and leaders have been extended without consulting the public. There has been no opportunity to bring about a change in policy direction. Concerns are greater where countries have already seen some democratic backsliding and have been criticized by civil society for using coronavirus to extend their mandate.

As a new International IDEA Technical Paper, Elections and COVID-19, sets out, democracy can also be undermined by holding elections during these times. For example:

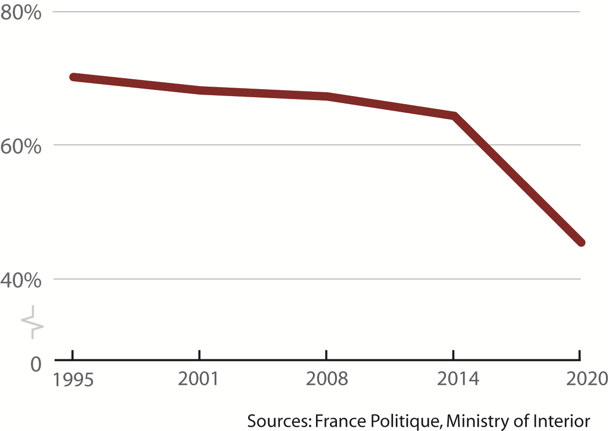

- turnout may decline, especially amongst groups more likely to be affected by the disease, and this undermines principles of inclusivity and equality in the electoral process (see Figure 1 for the example of decline in voter turnout in French municipal elections held on 15 March 2020 compared to the rate of turnout in previous elections);

- political campaigning may not be possible at a time where in-person interaction is either discouraged or prohibited in larger groups;

- the public debate may only focus on the current public health crisis, thereby preventing a wider discussion about other important topics;

- an unscrupulous government may use emergency restrictions on rights to repress opposition candidates or critical media and individuals, making elections held under emergency conditions less free and less fair than they should be.

Figure 1. Voter turnout in French municipal elections

Electoral innovation

There are ways that democracy could be kept on track and many countries have shown considerable innovation and quick thinking in adapting to this new scenario. In the United States, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) developed recommendations on preventative actions for election officials and the general public which encourage voting methods that reduce contact with other people, the cleaning and disinfection of voting equipment as well as social distancing measures for in-person voting. In South Korea, the National Election Commission has communicated a range of special health and safety measures which include advance voting for confirmed Covid-19 patients in care centres to protect their right to vote.

In Bavaria, Germany all-postal voting mechanisms have been introduced which completely excludes in-person voting in order to mitigate health risks of contagion posed through close contact. Also, New Zealand‘s Electoral Commission is considering extending existing alternative voting arrangements, designed for voters unable to attend a polling station to vote in person, to all voters for its general election scheduled for 19 September 2020.

For countries that are planning to run elections despite the current health pandemic, lessons from other countries will be crucial. However, for countries where people lack access to clean water, disinfectants, protective clothing or a functional postal service there may be good reasons to either implement extraordinary measures or to postpone elections until a time when the threat of virus has dissipated.

Making democracy work

The International IDEA Technical Paper therefore makes recommendations for how policy-makers should continue. There is no one-size-fits all answer for every scenario, but there are general principles that should be applied. Inter-agency collaboration is essential and there should be:

- careful consideration of staff and public safety, constitutional constraints and procedures, and implications for democracy – inclusion, equality and accountability;

- logistical considerations for alternative voting arrangements;

- if proceeding with an election, processes for mitigating risks;

- if postponing an election, pathways for addressing the electoral issue at hand and stringent guidelines for caretaker arrangements; and

- public communication about the issues at stake, the reasons for the decision and the processes in place to safeguard democracy.

The global spread of Covid-19 has already profoundly impacted the health and welfare of citizens around the world. The decisions that policy-makers make about the holding of elections will have a further profound effect, shaping the health of democracy in the future.

Disclaimer: Views expressed in this commentary are those of the author, who is a staff member of International IDEA. This commentary is independent of specific national or political interests. Views expressed do not necessarily represent the institutional position of International IDEA, its Board of Advisers or its Council of Member States.

About the authors

Erik Asplund is a Programme Officer in the Electoral Processes Programme at International IDEA. He has worked directly with over a dozen electoral management bodies from around the globe. He is currently based in Stockholm, Sweden.

Toby James is a Visiting Academic at International IDEA and Professor of Politics and Public Policy at the University of East Anglia, UK. His most recent book is Comparative Electoral Management (Routledge, 2020).

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.