Legal aid cuts may mean excluded members of society are denied access to a vital part of our democratic system

Thousands of lawyers are today protesting outside courts at planned cuts to legal aid. Stuart Wilks-Heeg, Stephen Crone, and Andrew Blick considered this topic in the 2012 audit of UK democracy, identifying concerns about the difficulty citizens face in accessing legal aid, which have intensified since the coalition government was elected.

How have cuts to legal aid affected citizens’ ability to access the justice system? Credit: FruitMonkey, CC BY-SA 3.0

It is clearly necessary, if the rule of law is to be fulfilled, that all within a society should have access to justice if they require it, in order to ensure that their rights within the democratic system are upheld. Article Six of the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR), as incorporated under the Human Rights Act 1998, is now an important source of this fundamental right. It involves individuals being able to access both representation, regardless of their personal means, and to be subject to fair legal processes. However, a defined right of access to justice does not mean that all citizens have equal access to it in practice. As a former senior law lord once put it, ‘It has been said, with heavy irony, that justice in the UK is open to all, like the Ritz Hotel’. Given the costs of undertaking legal action, the availability, or otherwise, of legal aid is a particularly important factor in determining the extent of access to justice.

In a developed society such as the UK the complexity of the law serves to limit the citizen’s access to justice. The overall rise in the volume of parliamentary legislation is detailed elsewhere in this Audit (see Section 2.4.2). In a common law territory, the complexity is further compounded by the volume of so-called ‘judge-made law’. Finally, under the European Communities Act 1972, European Union law is given effect in the UK, making the overall picture more complicated still. Persons seeking access to justice, who are not themselves legal experts, will therefore need to acquire professional representation, which does not come cheaply.

Article Six of the ECHR requires that an individual who cannot afford representation should have it provided for them if to do so is necessitated by the interests of justice. But a previous UK Audit has noted that the principle of equality before the law:

[has never] meant equality of access to the law in the United Kingdom. Even the most obvious pre-requisite of such access – the provision of legal aid to enable those otherwise unable to pursue their rights in the courts – is not available for all types of case and has been subject to sharp financial reductions in recent years.

During the present Audit period a major change was instigated to legal aid in England and Wales by an official report by Lord Carter of Coles: Legal Aid – A market based approach to reform. The underlying purpose of the review was to achieve reductions in the rising costs of legal aid. As its title suggested the report proposed a shift to a free market system for the provision of legal aid. Carter envisaged that lawyers would have to compete with each other to secure contracts for providing criminal legal aid work; and that they would be paid on a fixed basis rather than according to time spent on cases. Carter’s proposals are being phased in over a period of time.

Further impact on legal aid will be felt in England and Wales as a result of the coalition government’s retrenchment programme, which is intended to reduce legal aid costs by £350 million a year. It sets out to achieve these aims by moving some areas of law either partly or wholly outside the scope of legal aid. These include large portions of the family law aspects of legal aid, except in cases where violence is taking place.

During the period under consideration in this Audit, the House of Commons Constitutional Affairs Select Committee and its successor, the Justice Committee, have carried out a number of inquiries into the legal aid system. In its first report on this subject during the current cycle, on civil legal aid, the Constitutional Affairs Committee noted various concerns. A bureaucratic form of auditing introduced in 1999 known as ‘cost compliance’ was widely criticised as penalising some more professional firms and rating more highly those who were less trusted. The committee held that solicitors were not being adequately recompensed for their efforts. There were problems with recruiting young new entrants into legal aid work. Work on criminal and asylum cases had produced pressure on the civil legal aid budget; and the government was resistant to providing extra funding. Finally, the needs of many in society were not being sufficiently provided for, ‘often among those who are most vulnerable’.

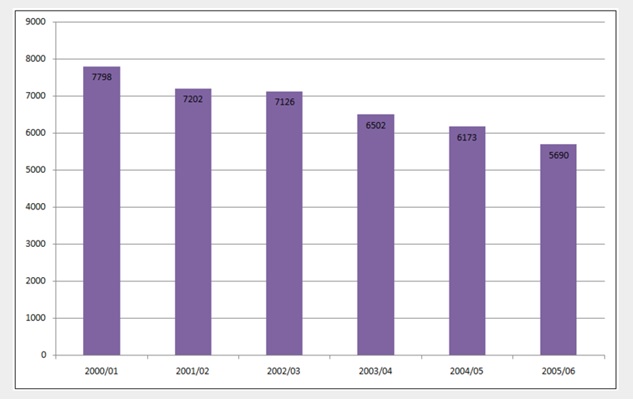

In the same 2004 report, the committee identified some underlying concerns about the legal aid system. It found that while ‘no country spends more money per capita on legal aid than England and Wales […] over the last decade [the system] has come under considerable financial strain’. The number of ‘acts of assistance’ was increasing. But fewer solicitors held civil legal aid contracts with the Legal Services Commission (LSC, which is responsible for the legal aid system): with those figures dropping from 4,854 in 2001 to 3,632 in March 2006. There is another way of analysing the overall decline in solicitors’ involvement in legal aid. Since firms usually hold contracts for more than one classification of law, rather than considering simply how many firms held a contract of some kind with the LSC, the total number of contracts held across the 12 different legal categories can be assessed. There was a steady overall decline, as Figure One shows, which amounted to 30 per cent over the period.

Figure One: Civil contracts held in all categories of law, excluding for personal injury

Source: Constitutional Affairs Select Committee (2007)

However, behind this headline figure, some categories rose dramatically, such as public law (by 411%); and community care (181%). The three largest percentage drops were recorded by consumer law (79); employment law (46%); and debt law (35%). The figures provided by the committee did not include contracts held in the personal injury category.

Evidence exists that one consequence of this overall downward trend was that, in some parts of England and Wales, insufficient legal aid services were available. For instance, mental health services were apparently lacking in East Anglia, Hull and North Yorkshire; while there was said to be a lack of criminal legal aid in South West England, South West Wales, and North East England.

Responding to the implementation of the proposals made by Lord Carter in 2007, as described above, the Constitutional Affairs Committee criticised the policy as having been introduced ‘too quickly, in too rigid a way and with insufficient evidence’. The system as a whole was being changed to deal with rising costs. Yet the only serious increases in legal aid costs were limited to public law cases involving children; and Crown Court defence work.

The coalition cuts to legal aid have been a wide source of concern. In spring 2011, the Justice Committee described them as ‘fundamental, extensive and bold’. It raised particular concerns about the plans to remove many areas of family law from legal aid, apart from where domestic violence was taking place. The Committee was ‘not convinced that using domestic violence as a proxy for the most serious cases is advisable […] If the Government does continue to use domestic violence as a criterion for eligibility, it should broaden the definition to include non-physical domestic abuse’. Gary Slapper and David Kelly have argued that:

the overhaul of the […] legal aid scheme will mean that people will be forced to settle divorce disputes out of court and to take out private legal insurance to pursue their claims. Vulnerable citizens will be likely to suffer…’

Some serious systemic problems have been identified in the legal aid system of England and Wales. As noted by the Constitutional Affairs Committee, spending per capita has been high – found by one study to be higher than any other comparable country. Yet, even before the present cuts, the system was struggling. Part of the answer to this puzzle may be that the legal aid system is often dealing with problems that arise from a failure to deal with issues earlier on in the process through the making and implementation of public policy, and through complaints and appeal processes operated by public bodies. Second, the legal system is structured in such a way as to create many formal occasions on which representation is required, even if producing little practical outcome. Third, unlike in some other territories, legal aid is contracted out to the private sector, rather than handled by public employees, which may lead to inflation of costs. Fourth, the government itself, through producing such large volumes of legislation, creates more cases which may necessitate the provision of legal aid.

We note that problems with the effectiveness of the legal aid system in England and Wales are an ongoing issue of democratic concern. They can mean that some of the most excluded members of society can be denied access to an important part of the democratic system. Uneven coverage is problematic from the point of view of effectively securing the rule of law for all. It is clear that funding is not the only issue involved. There are other matters, touched upon elsewhere in this Audit, that create strains on a system that is required to handle social problems that have not been addressed earlier on. However, given its current difficulties, and given that the underlying social problems are not likely to be addressed in the immediate future, the present policy of retrenchment can be assumed to create more problems still.

—

Note: This post is based on extracts from the 2012 Audit of Democracy, specifically section 1.2.4 Citizens’ access to justice. Please read our comments policy before posting. The shortened URL for this post is: buff.ly/1eBGNug

—

Stuart Wilks-Heeg, Andrew Blick, and Stephen Crone are the authors of the 2012 Democratic Audit report.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Cuts and a market approach to Legal Aid undermine democracy. “Justice in the UK is open to all, like the Ritz Hotel” https://t.co/zFdOXFcpzK

RT @richard3berry: Why are lawyers “on strike” today? Analysis from @democraticaudit’s 2012 audit of democracy explains… https://t.co/7z2y…

UK legal aid cuts may mean excluded members of society are denied access to a vital part of our democratic system https://t.co/Ua0Q2N7QZk

Legal aid cuts may mean excluded members of society are denied access to a vital part of our democratic system https://t.co/JyJiaXkWcp

#walkout4justice As lawyers protest, Democratic Audit takes a look back at the recent history of legal aid reform https://t.co/T9xCfmJ91p

As lawyers “strike” over legal aid, we consider difficulties citizens face accessing the system, pre- and post-2010 https://t.co/2xU1bvQm9L

MT @richard3berry: Why are lawyers “on strike” today? Analysis from @democraticaudit’s 2012 audit of democracy… https://t.co/ytC4Xx5nV3

New on DA: Legal aid cuts may mean excluded members of society are denied access to a vital part of our democracy https://t.co/3BxbSC2GDo