What is the extent of electoral fraud at English elections?

The Attorney General Dominic Grieve MP has apologised for controversial remarks about corruption among ethnic minority groups in the UK. In the 2012 audit of UK democracy, Stuart Wilks-Heeg, Andrew Blick and Stephen Crone examined the extent of electoral fraud in English elections, finding that instances had fallen in recent years after a sharp increase in the mid-2000s, but vulnerabilities remained in our system of electoral administration.

Are there sufficient safeguards against abuse of voting procedures to ensure fair elections? Credit: Ian Britton, CC BY-NC 2.0

The emergence of evidence of electoral malpractice in English elections during the 2000s ranks among the most concerning emerging developments identified by this Audit. Evidence of malpractice began to mount from 2005 onwards, after an election court convened in Birmingham found five men guilty of large-scale electoral fraud, involving thousands of postal ballots, at local elections in June 2004. In his written judgement, the election commissioner, Richard Mawrey QC, referred to ‘evidence of electoral fraud that would disgrace a banana republic.’

While the Birmingham case represented the most systematic proven case of attempted ballot rigging, there have been numerous other convictions for electoral fraud in the UK since 2000. Court cases relating to large-scale fraud in local elections in Slough in 2007 and Peterborough in 2004 resulted in six convictions each. Following a lengthy police investigation and two re-trials, five men were eventually convicted in September 2010 for electoral fraud offences in the Bradford West constituency during the 2005 general election (the first relating to fraud in a UK general election for almost one hundred years). In total, more than 100 people have been found guilty of electoral malpractice in the UK since 1994. The vast majority of convictions have involved postal or proxy ballots, often in conjunction with attempts to manipulate the electoral registers by registering bogus electors or adding electors to the register at empty properties.

The emergence of electoral fraud as an issue in UK politics cannot be divorced, therefore, from changes in electoral law since the 1990s, which introduced provisions for proxy voting and the widespread availability of postal voting. In particular, the introduction of ‘postal voting on demand’ via the Representation of the People Act 2000 created obvious opportunities for malpractice, especially when combined with a ‘rather arcane’ system of electoral registration. Outside of Northern Ireland, applications to appear on a local electoral register are largely taken on trust. Electoral Registration Officers (EROs) have no real scope to verify a voter’s identity, their eligibility to vote or whether they are already registered to vote elsewhere. In this context, it has been suggested that the practice of ‘roll stuffing is childishly simple to commit and very difficult to detect.’

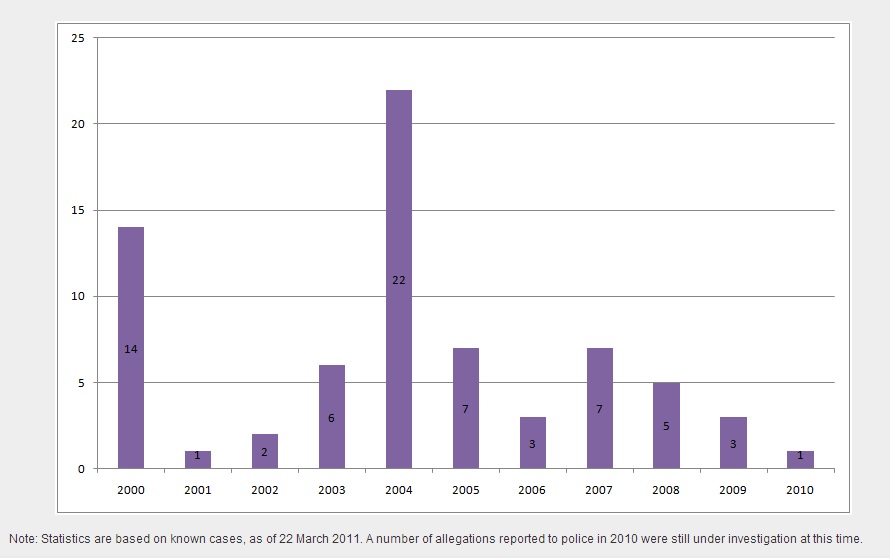

Figure One shows the number of known instances where defendants were found guilty of, or pleaded guilty to, electoral offences in a UK court from 2000-10. Although certain to underestimate the extent of fraud, these figures point to a very clear peak in offences in 2004, when all-postal voting trials were run in four English regions for the combined European and local elections. The graph also highlights that half of those found guilty of electoral malpractice over the decade committed their offences at elections in the period from 2003-05.

Figure One: Persons found guilty of electoral malpractice in the UK, 2000-2010, by year of election

Following the Birmingham judgement, the Electoral Administration Act of 2006 introduced a requirement for applicants for a postal ballot to supply ‘personal identifiers’ (their date of birth and signature), as a basis for the subsequent verification of their postal voting statement submitted at the time of voting. There have also been substantial improvements in the guidance provided by the Electoral Commission to electoral administrators and police forces and in the recording and monitoring of fraud allegations reported to the police. The clear decline in the number of convictions for electoral fraud since 2007 therefore suggests that recent efforts to safeguard the system appear to have been at least partially successful.

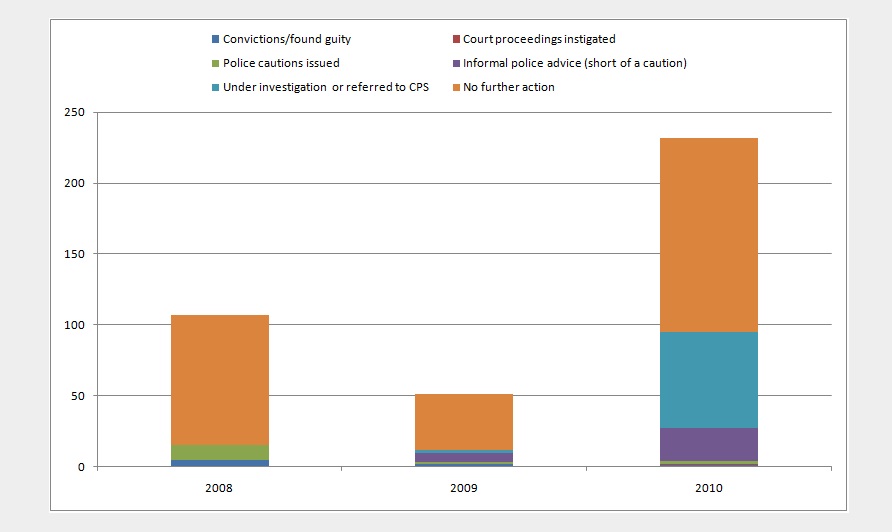

The vast majority of cases resulted in no further action being taken and, as the graph shows, the number of convictions represents a tiny proportion (around two per cent) of all cases investigated. Of the 232 cases reported to police in Great Britain in 2010, 137 resulted in no further action. At the time the Commission reported on the allegations in February 2011, just one had resulted in a conviction and two in formal police cautions, while court proceedings had been instigated in one further instance. In addition, 23 allegations had resulted in the police providing informal advice, with a further 68 allegations still under investigation or awaiting advice from the Crown Prosecution Service. However, these figures also hint at wider evidence of malpractice than is captured by the number of convictions. From 2008-10, around one-tenth of cases examined by police resulted in the police issuing either formal cautions or providing informal advice short of a caution.

Figure Two: Outcome of cases involving electoral malpractice allegations reported to the police, Great Britain, 2008-2010

Based on these findings, the Commission’s view is that levels of fraud are minimal, and that any repeat of the large-scale cases from 2004 or 2005 is now unthinkable. However, such interpretations are contested by some lawyers, politicians and journalists. In March 2008, passing initial judgement on the Slough case, Richard Mawrey QC, again acting as election commissioner commented that: ‘to ignore the probability that [fraud] is widespread, particularly in local elections, is a policy that even an ostrich would despise.’ Jerome Taylor, a reporter for the Independent, who had been attacked while investigating allegations of fraudulent registrations in the London Borough of Tower Hamlets in 2010, described the (2011) Electoral Commission/ACPO report on electoral fraud allegations as ‘a bizarre exercise in asking Britain’s voters to keep calm and carry on’, adding that ‘for an organisation that is supposed to safeguard the integrity of our voting system, such complacency is shocking.’

To be fair, the Electoral Commission has never been complacent about the risk of electoral fraud and, while it regards the number of convictions and cautions for fraud as minimal, the Commission has never claimed that levels of fraud are therefore ‘acceptable’. The Commission has long recognised the need for further safeguards against fraud and, since 2004, has consistently argued for the introduction of a system of individual voter registration, to replace the existing system of ‘household’ registration. It was not until Labour’s Political Parties and Elections Act 2009 that provisions were made for a phased introduction of individual voter registration in Great Britain over a period of five years. Under this system, which was introduced in Northern Ireland in 2002 alongside others measures to tackle electoral fraud, all electors are required to provide their date of birth, signature and national insurance number when registering to vote.

Part of Labour’s reluctance to act more decisively when in government stemmed from the concern that a more secure system of voter registration may have the side-effect of further depressing levels of voter registration. The experience of introducing individual voter registration in Northern Ireland clearly indicated that a sharp drop in registration levels was likely. In 2010, the incoming Conservative-Liberal Democrat coalition opted to accelerate the introduction of individual voter registration, while introducing wider measures to prevent a sharp decline in registration levels and guaranteeing that no elector will be disenfranchised at the 2015 general election as a result of failing to submit personal identifiers (see Toby James’ recent post on Democratic Audit for further discussion). The impact of these reforms on the completeness and accuracy of Great Britain’s electoral registers will need to be carefully monitored over the next few years.

—

This post is based is based on extracts from the 2012 audit of UK democracy. For further discussion and full data sources see section 2.1.2 Registration and voting procedures. Please see our comments policy before posting. Shortlink for this post: https://wp.me/p3F3ol-ua

Stuart Wilks-Heeg, Andrew Blick, and Stephen Crone are the authors of the 2012 Democratic Audit report.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

[…] have been some cases of fraud in Britain, for sure. Stuart Wilks-Heeg recently analysed the number of people found guilty of electoral malpractice in the UK. The most […]

I find it very hard to believe that there is not substantial fraud particularly in marginal constituencies – I suspect that there is a conspiracy of silence by the parties – just as there is concerning electoral spending limits and the black arts of propaganda.

When I was involved in by-elections (a few decades ago) fiddling or stretching the rules was rife. (For instance, you could get a supporter to get a while lot of posters printed – and the supporter would then “lease” those posters to the campaign for a fraction of the cost – “because of course they would be used for multiple campaigns”)

Party head-quarters would parachute in “by-election teams” or “marginal constituency teams” in General Elections – often well versed in the black arts. Putting out black propaganda (for instance party A pretending to be party B and putting out unsubstantiated rumours about the relationship that the candidate for party C had with the retiring MP) is cheating, so who knows where they stop?

Volunteer workers would allow their enthusiasm/rabidness to run away with them and were difficult to control, so who knows what goes on when for instance canvassing for postal vote registrations or even when doing the main canvas.

What goes on in the USA tends to happen a few years later in the UK. We don’t effectively police large areas of our electoral system and the regulations are very loose. I cannot see the situation improving.