The decline in party membership across Europe means that political parties need to reconsider how they engage with the electorate

Is party membership still an important part of European political systems? Ingrid van Biezen outlines results from a study, co-authored with Peter Mair and Thomas Poguntke, of party membership rates in 27 European democracies. She notes that party membership levels vary significantly between European countries, with Austria and Cyprus containing the highest levels as a percentage of national electorates. Despite this variation numbers are declining in almost all of the countries studied, which may mean that parties have to reconsider the forms of organisation appropriate to politics in the 21st century.

At the beginning of the twenty-first century, political parties in European democracies have clearly lost the capacity to engage citizens in the way they once did. There is scarcely any other indicator relating to mass politics in Europe that reveals such a strong and consistent trend as that which we see with respect to the dramatic decline of party membership.

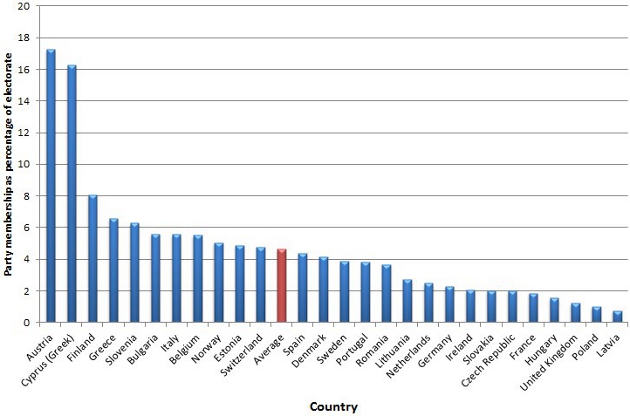

Figure 1, below, shows party membership as a percentage of national electorates in 27 European democracies. On average only around 4.7 per cent of the national electorates are members of a political party today. There is of course considerable variation between countries, with peaks for Austria and Cyprus, for example, where around 17 per cent of the electorates are still affiliated with a political party. At the other extreme, in countries such as Latvia and Poland the level of membership does not even reach 1 per cent.

Figure 1: Party membership as a percentage of national electorates

Notes: Figure for Latvia is from 2004, all other countries are from years between 2007 and 2009. For full data see: Ingrid van Biezen, Peter Mair and Thomas Poguntke (2012) ‘Going, going… gone? The Decline of Party Membership in Contemporary Europe’, European Journal of Political Research, 51(1): 24-56.

The degree of organisation in the newer Central and Eastern European democracies is significantly lower than elsewhere in Europe: nearly all post-communist democracies are below the European average, with the average membership level in the post-communist countries amounting to only half of that in the rest of Europe. The relative newness of these democracies, the absence of traditional cleavages in society, as well as the fact that most party organisations were established in an environment where they had access to modern means of communication and generous government subsidies at an early stage, have clearly discouraged efforts to build mass organisations, even in the longer term.

Conservative Party Conference (Credit: NCVO, CC by 2.0)

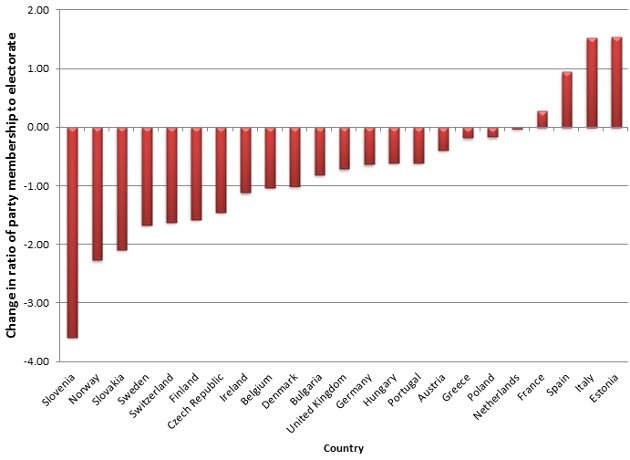

The decline of party membership that started in the last quarter of the previous century is visibly continuing in the present day. As Figure 2 shows, both the absolute membership levels and the membership ratios have plummeted nearly everywhere. In most of the older democracies, the decrease has been quite staggering. In the United Kingdom, France and Italy, for example, the parties have lost 1 to 1.5 million members in the last three decades, which corresponds to a total loss of about one to two-thirds of their original supporters. The Nordic countries have also suffered heavy losses, with the raw numbers of members about 50 to 60 per cent lower than before. In some countries the damage has remained more limited, although in all established democracies the number of members has decreased by at least 25 per cent. On average, the absolute number of members has almost halved since 1980.

Figure 2: Change in ratio of party membership to electorate since late 1990s

Notes: For full data see: Ingrid van Biezen, Peter Mair and Thomas Poguntke (2012) ‘Going, going… gone? The Decline of Party Membership in Contemporary Europe’, European Journal of Political Research, 51(1): 24-56.

Interestingly, older established democracies and ‘new democracies’ do not show any significant differences in terms of party membership trends. Even the parties in post-communist Central and Eastern Europe, despite their relatively short existence, have lost significant numbers of members. Many of the parties in these newly established democracies are struggling to consolidate, let alone strengthen, their already limited organisational presence on the ground. In fact, the decline in party members is even more pronounced in Central and Eastern Europe than in the West. That party memberships also declined after the democratic revolution debunks the expectation that the originally low degree of party political affiliation would be a reflection of the newness of the democratic system. Only in Southern Europe do we find exceptions to the general downward trend: Spain is the only (new) democracy where party membership has grown almost continuously since the transition to democracy. Nevertheless, even in Spain the average level of affiliation is relatively low and remains below the European average.

The trend suggests that both the nature and the significance of party membership have changed fundamentally. Party memberships are increasingly small, and increasingly less representative of the wider constituency of parties in social and professional, if not ideological terms. Those with a party membership are more likely to work in the public sector than non-members. The question is whether memberships have also become sufficiently distinct in terms of profile and activities that it might be reasonable to regard them as no longer constituting part of civil society – with which party membership has traditionally been associated – but rather as constituting the outer ring of an extended political class. In terms of background, education and employment, they may have more in common with the party central office or even the representatives of the party in public office than with the traditional party on the ground. This would suggest that the real social roots of political parties, to the extent that they exist at all, are now to be found outside the boundaries of the formal party and are made up of a loosely and horizontally organised myriad of supporters, adherents and sympathisers.

Despite the fact that some parties remain strongly committed to their membership organisations, and continue to seek to engage these memberships in internal decision-making processes, it seems that the vast majority of parties are relatively unconcerned about the erosion of their membership. Even the processes traditionally dominated by party cadres, such as candidate nomination and leadership selection, are increasingly open to sympathisers and supporters who are not part of formal party organisations. In addition, we are witnessing the emergence of alternative forms of organisation, such asBeppe Grillo’s Five Star Movement, which relies on social media and local meet-ups, and aims for a form of horizontal organisation to enable the democratic participation of citizens. Other parties, such as Geert Wilders’ Freedom Party in The Netherlands even eschew membership completely and are much more focused instead on reaching the general public through professional and modern marketing campaigns.

Party memberships in contemporary European democracies have now fallen to such a low level that they no longer seem to offer a meaningful indicator of party organisational capacity. This inevitably calls into question our dominant way of thinking about political parties as a meaningful linkage mechanism between the general public and the institutions of government. Especially since collateral organisations traditionally linked to the parties, the trade unions and the traditional churches, are experiencing a decline in levels of support that is almost as dramatic.

While political parties continue to play a major role in the elections and institutions of modern European democracies, it seems that they have all but abandoned any pretensions to being mass organisations. In the face of the current crisis of public trust and plummeting confidence in parties and politicians, the time has perhaps come for the parties to seriously consider what forms of political organisation might be appropriate to representative democracy in the twenty-first century.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy, on which it was originally published, or of the London School of Economics.

About the author

Ingrid van Biezen

Ingrid van Biezen

Ingrid van Biezen is Professor of Comparative Politics at Leiden University. Her research interests lie primarily in the field of comparative politics, political parties and party systems, democratisation and institutional development. Her publications include Political Parties in New Democracies: Party Organization in Southern and East-Central Europe (Palgrave MacMillan, 2003).

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.