What can political parties do to involve more women in party politics?

In most political parties the majority of members are men, which has implications for achieving equal representation at all levels of politics. Aldo F. Ponce, Susan E. Scarrow and Susan Achury find that this gender gap varies considerably between parties, and that having more women MPs helps to increase women’s participation at the grassroots level.

Picture: National Assembly for Wales/(CC BY 2.0) licence

There is a lingering stereotype of local party meetings as a bunch of men debating or deal-making in smoke-filled rooms. While the smoke has cleared thanks to changing rules and habits, the gender disparity often remains. Research in parliamentary democracies has consistently shown that women are less likely than men to participate in political parties. This participation gender gap has persisted despite narrowing gender gaps in education, employment, and in other types of political activities.

This is a problem for parties because having low numbers of female party members makes it harder for parties to credibly represent and respond to their female supporters. For example, in parties which let their members vote on important party decisions, half the population may be conspicuously under-represented. Having fewer women members may also complicate party efforts to nominate women candidates.

However, while gender gaps for member participation are widespread, they are not universal, and where they exist, their size varies greatly by country as well as by party. This raises the questions: why are some parties more successful than others in closing grassroots gender gaps, and can other parties learn any lessons from their success? In a recently published article we investigate these questions using data from parties in European parliamentary democracies.

How big is the gap?

Various measures of party life come to the same conclusion: men participate in political parties at much higher rates than women. For instance, surveys of party members in 10 European democracies found that only about one-third of members were women. Stark gender differences are also evident in the 2010 European Social Survey, which is the most recent edition of this survey that asked respondents which party they supported, and then separately asked if they were a party member. Importantly, however, this survey finds large differences in the size of the gender gaps, including between parties in a single country.

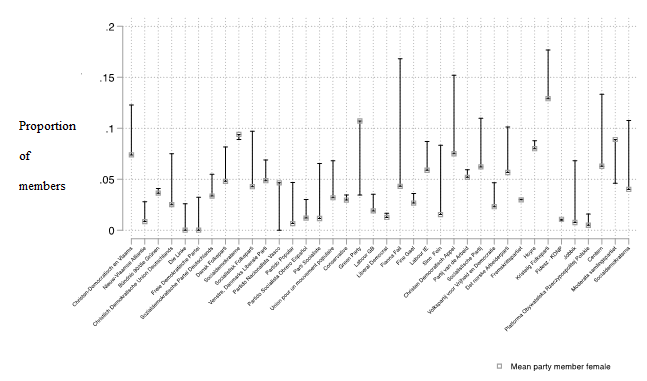

Figure 1 graphically displays some of these differences for 38 randomly selected parties, showing what proportion of each party’s supporters identified as party members. The size of the vertical line indicates the gap between the proportion of men and women supporters who say they are members. As expected, in most cases men’s participation is higher, but the figure makes clear how much this varies across parties.

Figure 1: Differences in the proportion of party supporters who are also members between men and women for 38 parties

Why are women more likely to join some parties than others?

To explain these cross-party differences in grassroots participation, we focused on three party-level factors that have been found to boost women’s elite-level participation in parties: having women’s sub-organisations; having quotas for women candidates; and having high numbers of women in party legislative delegations. We investigate whether these factors have trickle-down effects that boost grassroots participation.

We considered several ways this might occur. For instance, these factors could increase party efforts to recruit women as party members and activists (increased party demand). Female party leaders may strengthen women’s partisan engagement by recruiting volunteers to help with their own re-selection, or by favouring women’s appointment to internal party posts. Similarly, local parties following quota requirements may work harder to recruit women members to fill the numerous slots on local government slates.

Changes affecting a party’s elite level might also increase the attractiveness of grassroots participation (increased supply of interested activists). For instance, women might find more reason to participate in parties if they see women leaders and legislators as role models, or if parties with more women at the top emphasise issues that are of greater interest to women supporters. Quotas may motivate women to join by providing clearer opportunities for women activists to pursue political careers of their own.

To identify which of these factors might be associated with closing the participation gender gap, we estimated several multivariate econometric models – which control for other factors affecting membership and participation – using participation data from the 2010 European Social Survey, and data on party rules and leadership from the Political Party Database. We find no direct effects of party quotas, whether voluntary or required by law. However, we do find that women’s grassroots participation as members and member-activists rises as women gain more of the party’s parliamentary seats. Because non-members do not change their behaviour, this seems to be more about party mobilisation efforts rather than being a more general role-model effect. Parties with women’s sub-organisations have more women members, but that does not translate into higher numbers of active women members.

Closing the grassroots gender gap?

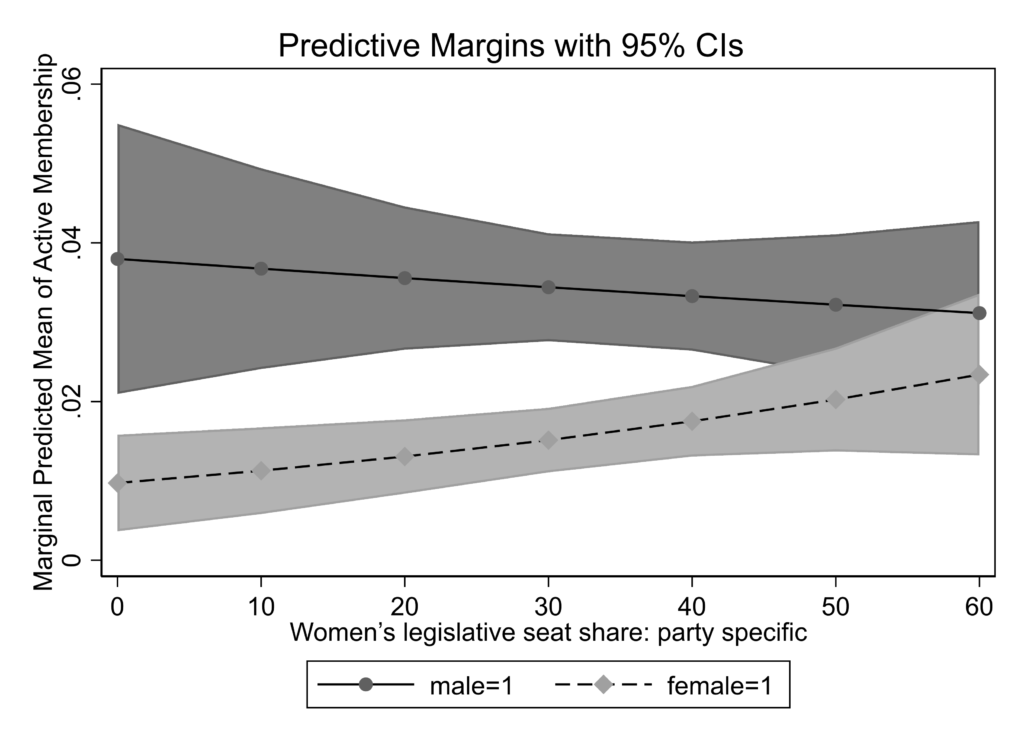

Do factors that stimulate women’s grassroots participation also reduce the participation gender gap? The answer depends on their relative impacts on men’s and women’s participation. If they have identical effects, the gap will not change. They can only close the gap by boosting women’s participation more than men’s – or by depressing men’s engagement. The news on closing the gender gap is a little less positive than that on boosting women’s activism. Thus, women’s sub-organisations do not help to close the membership or activism gaps, nor do quotas play any direct role. However, we do find narrower grassroots gender gaps in parties with more women MPs. As Figure 2 illustrates, this is happening primarily because women are becoming more active, whereas men’s participation rates stay about the same. Apparently, the mechanisms that increase women’s party activism do not reduce the incentives for men to get involved.

Figure 2: Difference in activism rates for men and women, depending on women’s legislative seat share

Lessons learned

The good news about this finding is that parties in many countries have been electing more women legislators. For instance, the 2019 UK general election elected a record number of women MPs. At the party level, women’s seat share now ranges from 24% of Conservative MPs to 51% of Labour MPs, and as high as 64% of Liberal Democrat MPs. In parties where such shifts occur, past experiences provide reasons to expect that changes may be coming at the grassroots as well.

However, our findings also suggest that this mechanism alone may not fully close the participation gender gap. As a result, parties may want to adopt policies targeted explicitly towards this goal, for instance by deliberately organising a variety of campaign activities to appeal to a broader range of supporters. Whatever they do, the other good news is that activating more women supporters does not seem to deter men from being active in the party. As a result, increasing levels of women’s grassroots party activism is a goal that deserves support from everyone seeking to build more active party memberships.

This article gives the views of the authors, and not the position of Democratic Audit. It draws on the authors’ recently published article, Ponce, A., Scarrow, S.E., & Achury, S. 2020. ‘Quotas, Women’s Leadership, and Grassroots Women Activists: Bringing Women into the Party’, European Journal of Political Research.

About the authors

Aldo F. Ponce is associate professor in the Department of Political Studies at the Center for Research and Teaching of Economics (CIDE-Mexico City). His research on political parties and legislatures has appeared in several leading journals.

Susan E. Scarrow is professor of political science at the University of Houston. Her publications on political parties and representation include Beyond Party Members: Changing Approaches to Partisan Mobilization (Oxford University Press: 2015).

Susan Achury is a visiting assistant professor in the Department of Political Science at Miami University. Her research focuses on comparative political institutions, with a focus on judicial politics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.