The UK’s Changing Democracy: The 2018 Democratic Audit

Three fast lessons and three slow lessons for UK democracy in 2019

The Brexit process has exposed serious flaws to the UK’s democratic institutions. In this post, based on a speech given at the launch of The UK’s Changing Democracy: The 2018 Democratic Audit, Joelle Grogan outlines six democratic lessons we should learn in 2019. The book is published by LSE Press, and can be downloaded for free here.

How well does the UK’s democracy protect human rights and civil liberties?

A foundational principle of liberal democracy is that all citizens are equal, and so the protection of fundamental human rights is of critical importance for democratic effectiveness. In many countries a statement of citizens’ rights forms part of the constitution, and is especially enshrined in law and enforced by the courts. This has not happened in the UK, which has no codified constitution. Instead, in an article from The UK’s Changing Democracy: the 2018 Democratic Audit, Colm O’Cinneide evaluates the more diffuse and eclectic ways in which the UK’s political system protects fundamental human rights through the Human Rights Act and other legislation, and the courts and Parliament.

The UK’s democracy is in danger of backsliding – but current policy proposals are not the right fix

Jessica Garland from the Electoral Reform Society responds to our recent publication, The UK’s Changing Democracy, and highlights crucial areas for immediate reform, particularly in the areas of political finance and online advertising.

How transparent and free from corruption is UK government?

For citizens to get involved in governing themselves and participating in politics, they must be able to find out easily what government agencies and other public bodies are doing. Citizens, NGOs and firms also need to be sure that laws and regulations are being applied impartially and without corruption.In an article from our book, The UK’s Changing Democracy: The 2018 Democratic Audit, Ben Worthy and the Democratic Audit team consider how well the UK government performs on transparency and openness, and how effectively anti-corruption policies operate in government and business.

Losing the ‘Europeanisation’ meta-narrative for modernising British democracy

Contrary to claims of Britain’s enduring political and constitutional distinctiveness, in the period from 1997 to 2016 the UK in fact modernised its polity by following several strong ‘Europeanisation’ trends. British democracy came to increasingly resemble other European liberal democracies in some fundamental ways. Yet now this meta-narrative may be lost following Brexit. Patrick Dunleavy explores some implications of the UK’s possible lapse back into rudderless idiosyncrasy.

Micro-institutions in liberal democracies: what they are and why they matter

Liberal democracies combine core ‘macro-institutions’ (like free elections and control by legislatures) with swarms of supportive ‘micro-institutions’. By contrast, semi-democracies keep only the façade of macro-institutions, subverting a range of critical micro-institutions so as to make political competition and popular control a hollow sham. Drawing on a new book, Patrick Dunleavy explains why these developments mean that political science has to get a lot more granular and sophisticated, instead of focusing just on ‘toy models’.

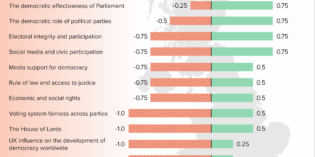

Auditing the UK’s democracy in 2018: Core UK governance institutions show sharply declining efficacy

Today we are publishing The UK’s Changing Democracy: The 2018 Democratic Audit, a systematic assessment of the country’s democratic institutions, large and small. Previous audits of the UK’s democracy, including the most recent in 2012, have generally found that, overall, the quality of our democratic institutions have improved over the past twenty years. However, Patrick Dunleavy and Alice Park find that this year’s Audit shows unprecedented declines in the core institutions of the UK’s democratic system, particularly at the centre.

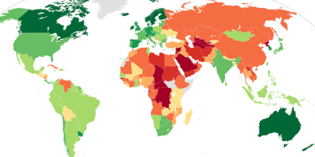

In comparative league tables of liberal democracies the UK’s democracy is judged to be First Division, but not Premier League

Ranking established liberal democracies against countries that are still developing a democratic polity risks awarding the long-lived countries ‘ceiling’ scores at the top of the table – feeding complacency amongst their elites and domestic publics that they can now rest easy on their laurels. However quantitative rankings typically do not treat the UK in this manner. Instead they assign it to a ‘good but not great’ category, well behind the states leading democratic good practice. For our new book, The UK’s Changing Democracy: The 2018 Democratic Audit, Patrick Dunleavy explores why.

How democratic and effective are the UK’s civil service and public services management systems?

Citizens and civil society have most contact with the administrative apparatus of the UK state, whose operations can powerfully condition life chances and experiences. In an article from our forthcoming book, The UK’s Changing Democracy: The 2018 Democratic Audit, Patrick Dunleavy considers the responsiveness of traditionally dominant civil service headquartered in Whitehall, and the wider administration of key public services, notably the NHS, policing and other administrations in England. Are public managers at all levels of the UK and England accountable enough to citizens, public opinion and elected representatives and legislatures? And how representative of, and in touch with, modern Britain are public bureaucracies?

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.