NHS Foundation Trusts have been a source of democratic experimentation for the past decade

Campaigners are promoting a wide range of reforms for the UK’s democratic system, including changing the electoral system, lowering the voting age or allowing people to vote online. While many look overseas for examples of how these innovations work in practice, Richard Berry explains in this post that each has already been introduced at NHS Foundation Trust elections. Although public participation in these elections is lower than hoped when Foundation Trusts were established in 2004, he argues, the research community could learn a great deal by studying how they conduct elections.

NHS Foundation Trusts have introduced a variety of democratic innovations in the past decade. Image: Sheila, CC BY-NC 2.0

NHS Foundation Trusts were established in 2004 with a new model for participation in the oversight and delivery of public services. Members of the public, patients and staff could become members of a trust, and then vote to elect governors, who would have a say in key decisions and hold the trust leadership to account.

Earlier this year on Democratic Audit, I shared findings of an analysis of participation rates in NHS Foundation Trust elections. These made disappointing reading. Membership levels for trusts tend to be low, and even among members the turnout for governor elections is small. Furthermore, large numbers of governors are elected unopposed, because insufficient numbers of candidates put themselves forward.

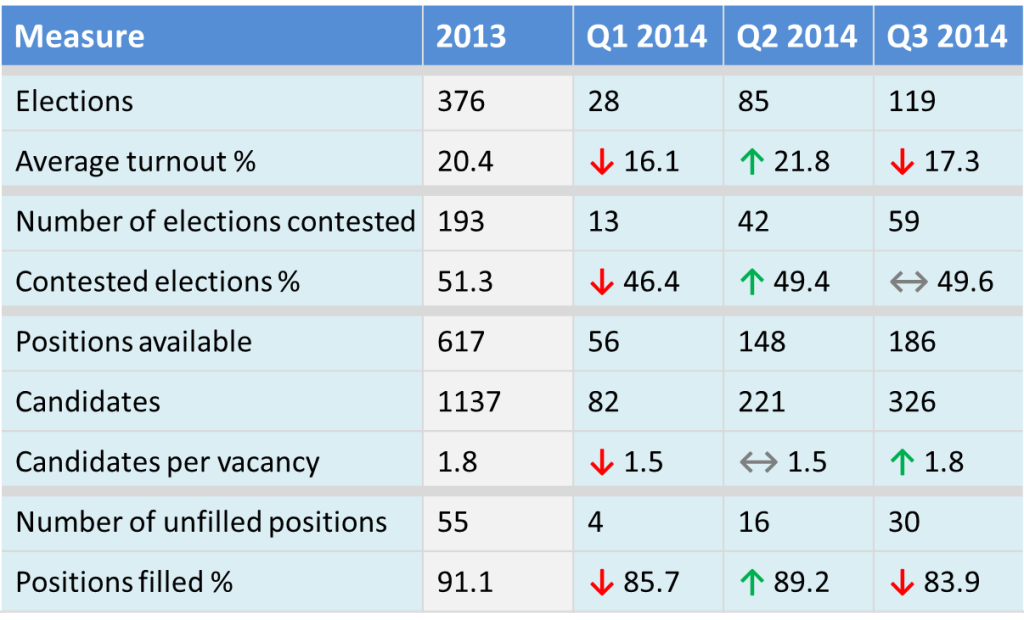

A new home for this participation data has now been established, at the Health Election Data website, which will be updated regularly with the latest results from trusts. Data so far this year suggests a continuation of previous performance (see Figure One below).

Figure One: Participation trends in NHS Foundation Trust governor elections, 2013-14

Foundation Trust elections have largely been overlooked by the democracy research community since their inception. Yet despite the low participation rates – an important finding in itself – analysis of these elections produces a number of interesting results, and reveals some electoral practices that might be worth adopting in other types of election.

Party membership

A large majority of candidates for governor elections stand independently of any political parties. This seems to put Foundation Trusts in the same category as parish councils, as elected but largely non-partisan public bodies. Although unlike parish councils, Foundation Trusts spend huge amounts of public money, and deal with an issue, healthcare, that is consistently at the top of the public’s list of policy priorities.

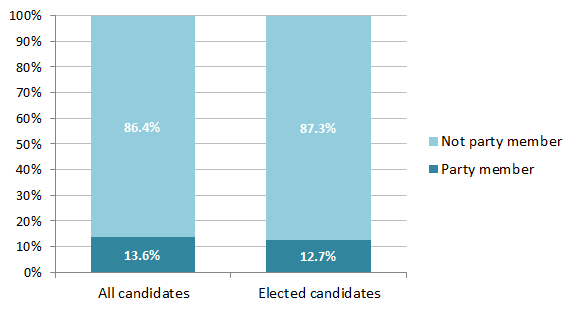

Parties do not nominate official candidates for governor elections, but most trusts ask candidates to declare any party memberships. For these trusts, only 14% of candidates declare any party membership, while 86% do not. One question I considered in a recent analysis of 135 elections in 2013-14 was whether party membership has any impact on electoral chances. It doesn’t: party members were just as likely to be elected as a governor as non-party members (see Figure Two below)

Figure Two: Party membership among Foundation Trust governor candidates, all and elected

Electoral system

Campaigners have long advocated the introduction of proportional representation (PR) for UK elections. The system favoured by the Electoral Reform Society is the Single Transferrable Vote (STV): this is used for the Northern Ireland Assembly and in Scottish local government, but in England the only types of election to use it are NHS Foundation Trusts.

Trusts are permitted to use either First Past the Post (FPTP) or STV for their governor elections, and STV is a very popular choice. Among elections conducted so far in 2014, about 59% were under STV, and 41% under FPTP. Although we might question the utility of a proportional system for mainly non-partisan elections, Foundation Trusts still provide a rich source of information about how the system operates. One important finding of my analysis is that female candidates are significantly more likely to be elected under STV than they are under FPTP in Foundation Trust elections (the role of gender in trust elections is discussed further below).

Votes at 16

While a great deal of fuss was made, rightly, over the extension of the franchise to 16 and 17 year olds for the Scottish independence referendum, few people seem to have realised that voters aged under 18 have been able to participate in Foundation Trusts for the past decade. The norm is that trusts allow anyone aged 16 to join, and therefore stand or vote in a governor election – for some trusts the age threshold for membership is even lower. To date no research has been done on the participation of young people in these elections, however.

Online voting

Like votes at 16, there is an ongoing debate in the democracy field about the introduction of online voting. This reform was first piloted by Lancashire Teaching Hospitals trust, with encouraging results: 43% of voters who opted not to receive the postal ballot pack voted, much higher than normal, and e-voters were more likely to be younger people. The Sheffield Children’s Hospital trust also allowed members and staff were to vote online for their governors at elections this summer. Unfortunately, this trust does not publish turnout figures for its elections, so it is difficult to draw conclusions about its success on that occasion.

Gender

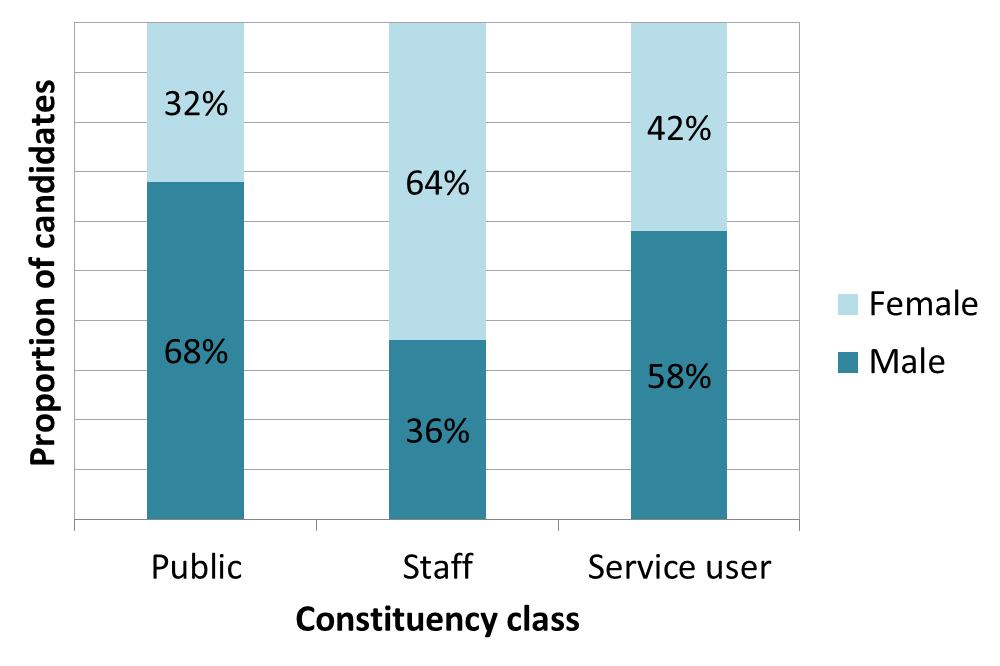

Women make up a sizeable proportion of the candidates for NHS Foundation Trust elections. While at general elections only around a quarter of candidates nominated by the major parties are female, for Foundation Trust elections 40% of all candidates are female. This is partly explained by the fact that many governors are elected from among NHS staff, the majority of whom are women (see Figure Three below). Excluding staff elections, women comprise a third of all candidates.

Women perform disproportionately well in NHS elections. While 40% of candidates are women, 42% of those elected (in contested elections) are women. Interestingly, this success is not driven by results in staff elections: female candidates are much more likely to be elected when standing for a public constituency, than they are when standing for a staff post.

Figure Three: Proportion of male and female candidates by constituency class, 2013-14

Participation levels in Foundation Trust elections tend to be highest in the early years after its establishment, suggesting that initial public enthusiasm for this form of engagement wanes over time. Trusts need to learn from each other the best ways of engaging their staff, patients and local communities. Further research into some of the trends and innovations discussed here would be a good start.

—

Note: this post represents the views of the author, and not those of Democratic Audit or the LSE. Please read our comments policy before posting.

—

Richard Berry is a Research Associate at Democratic Audit and the LSE Public Policy Group. He is a scrutiny manager for the London Assembly and also runs the new Health Election Data website. View his research at richardjberry.com or find him on Twitter @richard3berry.

Richard Berry is a Research Associate at Democratic Audit and the LSE Public Policy Group. He is a scrutiny manager for the London Assembly and also runs the new Health Election Data website. View his research at richardjberry.com or find him on Twitter @richard3berry.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

E-voting, #votesat16, STV – the NHS is quietly experimenting with elections: @richard3berry on @DemocraticAudit https://t.co/uQ2hNu4R5M

NHS Foundation Trusts source of democratic experimentation for the past decade https://t.co/HqTcaGGjpy @EmilyAGraham2 @clivemitchell1

My post on how the NHS is experimenting with e-voting, #votesat16, and STV for @DemocraticAudit https://t.co/rCQ7LQVTAU

NHS Foundation Trusts have been source of democratic experimentation for 10 yrs: @richard3berry on @DemocraticAudit https://t.co/uQ2hNu4R5M

NHS Foundation Trusts have been a source of democratic experimentation for the past 10 years, says @richard3berry https://t.co/nUbRfbC6Ul

NHS Foundation Trusts have been a source of democratic experimentation for the past decade https://t.co/lnTZIqdp7i https://t.co/LROusMIavV

NHS Foundation Trusts have been a source of democratic experimentation for the past decade https://t.co/gJCrvWUjet