10 years after NHS Foundation Trusts were created, their democratic processes are failing

The first Foundation Trusts were launched ten years ago this week, in April 2004. This new model was designed to increase the autonomy of NHS organisations and make them democratically accountable to local communities. The model may have succeeded on the former objective but on the latter they have fallen far short of expectations, argues Democratic Audit’s Richard Berry. In this post he shares findings from new research into participation levels in Trusts’ democratic processes.

NHS paramedics discuss who to vote for at their Trust’s next Council of Governors election. Credit: Kenjonbro (CC BY-NC-SA)

“Direct elections will help to ensure that NHS hospitals work more closely with the local communities they serve… The principle is that we want to ensure that local staff and local members of the community have a greater say in how local hospitals [are run]. That must be right. If we are to achieve more responsive local services… there has to be a much greater local element of accountability than there has been to date.”

That was Alan Milburn, former Secretary of State for Health, speaking in Parliament in 2003 during a debate about the creation of NHS Foundation Trusts. Launched ten years ago this week, in April 2004, the Foundation Trust model was designed to allow NHS hospitals and other services to be run more autonomously.

To achieve Foundation status, NHS organisations need to show they can effectively provide services and manage their finances independently. They must also develop new democratic processes. Firstly, staff, patients and the public are able to become members of a Foundation Trust. Secondly, this membership then comprises the electorate that elects a Council of Governors, the body which holds to account the Board and executive of the Trust.

To test the democratic credentials of Foundation Trusts, I collected data on their membership levels and recent Governor elections. Data was collected for 60 Trusts, representing about 40% of the total number. The findings are troubling in a number of respects, including:

- Foundation Trust membership levels are tiny, relative to the size of the communities they serve.

- Half of all elections to Councils of Governors are uncontested, with large numbers of vacant posts because too few candidates put themselves forward.

- Voter turnout at contested elections is low, averaging just 20%.

- Transparency of election information is poor across the sector, with only a small minority of Trusts publishing details of upcoming and recent elections online.

Membership

Members of Foundation Trusts are divided into several categories:

- Staff: Almost all Trusts operate a policy of automatically enrolling Trust employees as members, allowing individuals to opt-out if they wish to.

- Public: Anyone who lives in the community served by the Trust can become a member. Some Trusts also allow anyone in England to join.

- Patient: A minority of Trusts have a membership category for people who are currently using or have recently used Trust services, with some also distinguishing between patients and carers – most Trusts do not separate either of these groups from the general public membership.

The priority when Foundation Trusts were established was to ensure high levels of membership among these groups. As Alan Milburn argued in Parliament:

“NHS Foundation Trusts are a membership-based organisation and we want to ensure, as far as we can, that as wide a swathe of the local community as possible become members of NHS Foundation trusts… It is important that the membership of NHS Foundation Trusts is as large as possible.”

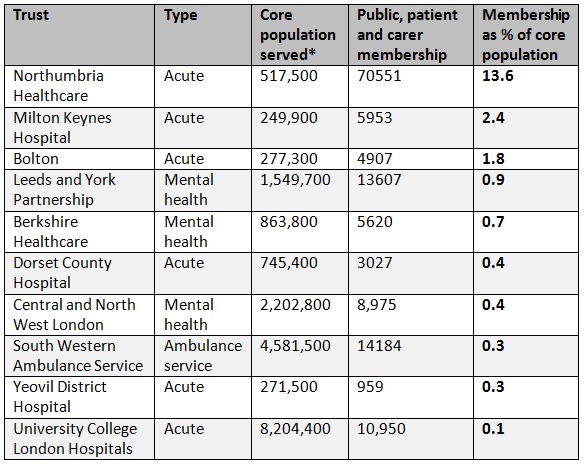

I looked at a small number of Trusts in detail – of different types and located in different regions across the country – to assess their public and patient memberships. This analysis suggested that membership levels are tiny, compared to the populations served by Trusts, although there are some notable exceptions.

Table 1: Membership levels and core populations for selected NHS Foundation Trusts

*Core populations are defined by the Public Constituency set out in Trust constitutions (available from Monitor), excluding any ‘rest of region/England’ constituency. Mid-2011 population estimates from the Office of National Statistics.

*Core populations are defined by the Public Constituency set out in Trust constitutions (available from Monitor), excluding any ‘rest of region/England’ constituency. Mid-2011 population estimates from the Office of National Statistics.

Elections

Participation in NHS Foundation Trusts election is very low. Elections are held for public Governors (usually in geographical constituencies), patient Governors and staff Governors (usually in profession-based constituencies). Other Governors may be appointed without election from partner organisations such as a local authority, although the patient and public Governors must comprise a majority.

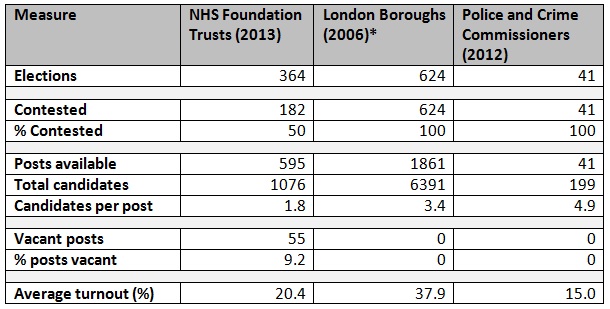

I compiled data for 364 elections held across 60 Trusts in 2013, with a total of 595 Governor posts available. I found that exactly half of all elections (182) were uncontested – the number of candidates was the same or less than the number of Governor posts available, so candidates were elected without a public vote. 55 posts were left vacant in total. There were a number of exceptional cases where a large number of candidates stood in a single election: for instance, a public Governor election for University College Hospitals London NHS Foundation Trust had 12 candidates for a single post.

The average turnout at Trust elections was just 20.4%. This is the proportion of Trust members voting; as a proportion of the local population as a whole, turnout is much lower. There was huge variation in turnout levels. Among the public Governor elections, the highest was 50.7% and the lowest was 2.9%. At one patient Governor election for Northumberland, Tyne and Wear NHS Foundation Trust – electing a representative for young service users – there were more candidates standing (four) than votes cast (three).

These results compare poorly to other types of election, even those which are thought to be marked by low participation levels. Table 2 below shows how participation in Foundation Trust elections compares to London Borough and Police and Crime Commissioner elections on several measures.

Table 2: Participation in NHS Foundation Trust (sample), London Borough and Police and Crime Commissioner elections

*London Borough elections in 2010 were held concurrently with the general election, so turnout figures are not comparable. NHS Trust turnout refers to Trust members only; other elections refer to everyone on the electoral register.

*London Borough elections in 2010 were held concurrently with the general election, so turnout figures are not comparable. NHS Trust turnout refers to Trust members only; other elections refer to everyone on the electoral register.

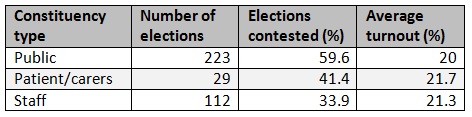

I tested whether a range of different factors affected participation levels in elections, specifically the constituency of the election and the age, type and size of the Trust. The findings suggest that none of these factors play a significant role in determining whether an election will be contested or election turnout.

Considering constituency type, the data does suggest that elections for public Governors are more likely to be contested than either patient/carer Governors or staff Governors, although the public category also has a lower average turnout. One possible interpretation is that public constituency elections tend to attract a relatively large number of committed activists as candidates, but fail to engage the wider local community.

Table 3: Participation in NHS Foundation Trust elections in 2013 (sample) by election constituency

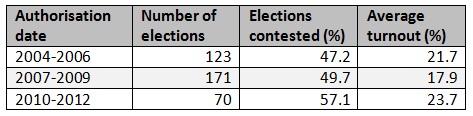

The age of the Trust is based on its authorisation date – the date at which it achieved Foundation status. It might be assumed that older Trusts would have higher participation rates, as they have had greater time to engage and inform the local community. However, newer Trusts tend to have higher contestation and turnout rates, as shown in Table 4. This may be an effect of new Trusts learning from the best practice of older Trusts when designing democratic structures.

Table 4: Participation in NHS Foundation Trust elections in 2013 (sample) by Trust authorisation date

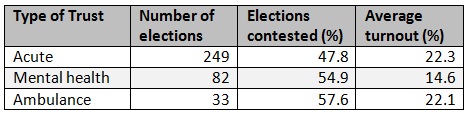

The ‘type’ of Trust is based on the services provided, with three categories: acute, mental health and ambulance service. Acute Trusts tend to cover smaller areas than mental health and ambulance Trusts, with services used more regularly by a greater proportion of the community. This, however, does not translate into higher participation levels, as shown in Table 5.

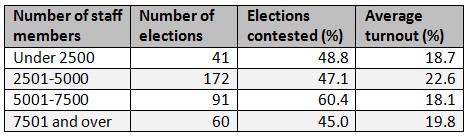

Table 5: Participation in NHS Foundation Trusts elections in 2013 (sample) by type of Trust

To estimate the size of each Trust, I used to data on the number of Trusts members in the staff constituency. As almost all Trusts appear to operate a policy of automatically enrolling employees as Trust members, this gives a good indication of Trust size. It might be assumed that smaller Trusts would have higher participation levels as they are more easily able to engage a clearly defined local community; alternatively larger Trusts may be able to devote greater resources to public engagement. The analysis is inconclusive, however, with no clear trend in contestation or turnout rates.

Table 6: Participation in NHS Foundation Trust elections in 2013 (sample) by size of staff membership

Transparency

Information about elections to Foundation Trusts is generally unavailable to the public. Of the 60 Trusts for which I collected data, only 13 published full detailed election results and upcoming election notices on their websites (21.7%). Others Trusts gave overviews of which elections had been held and who won in the annual reports, but this does not represent timely or accessible feedback for ordinary voters.

The unpublished information included in my analysis had to be obtained via Freedom of Information (FOI) responses. In many cases I found Trusts refused to release detailed information about elections, although in some instances these decisions were overturned after an internal review. The information withheld and reasons given included:

- The most common refusal was from Trusts which declined to release the names of losing candidates – they considered this to be exempt from FOI because it was personal information. In one case a Trust also refused to release the names of winning candidates.

- Several Trusts claimed membership and election information was already published on their website, even where this was not the case.

- Several Trusts stated that detailed breakdowns of voting were not available because they was held by a supplier rather than by the Trust (most Trusts use electoral services companies to run their elections).

- One Trust claimed that a detailed breakdown of voting was not available because it used the Single Transferrable Vote electoral system.

Conclusions

The Foundation Trust model was designed to enhance democratic engagement between NHS services and the communities they serve. With participation in democratic processes at such low levels 10 years after Foundation Trusts were first established, the inevitable conclusion is that the experiment has failed. No organisation can claim direct electoral legitimacy when only a tiny proportion of the community is voting, and half of all elections go uncontested. Furthermore, the lack of transparency about elections to Foundation Trusts, which are public bodies, is unacceptable.

Although better transparency and public engagement may help improve participation, it is clear that more significant reforms need to be considered. There are a number of ways in which this can be done, although the various options are not mutually exclusive.

Ways in which Foundation Trusts could adapt their own structures and processes include:

- Re-designing constituencies: the large variation in turnout the numbers of candidates across Trusts elections may suggest that constituencies of certain types (for instance, larger or smaller geographical coverage) may have higher participation. Further analysis would be required to establish this.

- Increasing the powers of the Councils of Governors, for instance in the appointment of Trusts managers, to encourage people that participation in these elections can lead to meaningful change.

- Aligning Foundation Trusts elections with other types of election. Before 2004 the Government suggested people could be given the opportunity to join Trusts when they registered to vote, but this has not happened. Furthermore, Trust elections are held at different times throughout the year and conducted only by post – co-ordniating them with other local elections may increase participation.

Beyond Foundation Trusts themselves, wider reforms may offer a better route to democratic engagement in the NHS:

- Establishing democratic processes within Clinical Commissioning Groups. These are the new bodies that oversee and commission local NHS services. These have a more community-based remit and have the power to shape the direction of NHS services as a whole.

- Giving more power to Health and Wellbeing Boards, new local government bodies which allow elected councillors to help shape health and social care services in partnership with NHS bodies.

—

The full dataset for this analysis is available to download here.

Note: This post represents the views of the author and does not necessarily give the position of Democratic Audit or the LSE. Please read our comments policy before responding. Shortlink for this post: buff.ly/1pJBvmu

—

Richard Berry is a researcher and managing editor for Democratic Audit. His background is in public policy and political research, particularly in relation to local government. In previous roles he has worked for the London Assembly, JMC Partners and Ann Coffey MP. He tweets at @richard3berry.

Richard Berry is a researcher and managing editor for Democratic Audit. His background is in public policy and political research, particularly in relation to local government. In previous roles he has worked for the London Assembly, JMC Partners and Ann Coffey MP. He tweets at @richard3berry.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

camiseta barcelona 2014

/forum/topic

Interesting blog on lack of democratic participation in NHS trusts from @richard3berry #demopart #nhscitizen https://t.co/im9ohVVXON

FT Governors: ‘the experiment has failed’. Great bit of research from @democraticaudit. This system needs changing! https://t.co/vgKsRo6zPf

#Democracy in (in)action – @democraticaudit on #NHS Foundation Trust elections. https://t.co/zGqArhgUa4 #localism

[…] This post originally appeared on Left Foot Forward and is co-authored by Democratic Audit’s Richard Berry. […]

How democratic are NHS foundation trusts? Interesting piece of research by @richard3berry – https://t.co/XwZ1VkWJJt

MT @democraticaudit: 10 years after #NHS Foundation Trusts were created, their democratic processes are failing https://t.co/36eMjUqoKJ

Out of interest, is there any particular reason that you picked up on that explains why Northumbria Healthcare’s membership seems so exceptionally high?

Thanks for the question Joe. Unfortunately not, I didn’t investigate this any further. I can say that they only other Trust that had similarly high % membership was Heart of England, but I didn’t include in the selection because the membership data was only an estimate.

I didn’t discuss it in the post but another interesting aspect of this topic is that Trusts have to set a minimum number of members in their Constitutions. Most are ridiculously low. For instance I think Milton Keynes has a rule that it must have a minimum of 24 (twenty-four) members, out of a population of 250,000. But this has not driven Northumbria’s high membership because they have a very low minimum too.

What are England’s least democratic elections? For NHS Foundation Trusts. https://t.co/RKH9GlhkAz https://t.co/luc4db2sBZ

NHS: failure of their democratic processes https://t.co/Fo5ZNLFune #pairrm

10 years after NHS Foundation Trusts were created, their democratic processes are failing https://t.co/6tWC9ozVgc

@dannywebster You’ve got bigger things on today but maybe some at KF would be interested in this (my research)? https://t.co/YPcTB5rYTr

Should you be able to join a Foundation Trust at same time you register to vote? FTs need to increase legitimacy https://t.co/Ci29qp2dst

Why were 9% of Foundation Trust governor posts left vacant at elections last year? New research published today https://t.co/b54jFWJhPk #nhs

10 years after #NHS Foundation Trusts were created, their democratic processes are failing https://t.co/wTocOmL2EA

Align Foundation trust elections with other local elections to boost participation in #NHS democracy https://t.co/GoOSVVq9z9

Important new research highlighting the democratic and participatory deficit in NHS Foundation Trusts in England.

https://t.co/FaGdQkJbDQ

10 years after NHS Foundation Trusts were created, their democratic processes are failing says DA’s @richard3berry https://t.co/ZRwCp0lbd3

RT @democraticaudit: 50% of all governor elections to #NHS Foundation Trusts are uncontested – compares very poorly to other elections http…

Which 2013 UK election had more candidates standing than votes cast? https://t.co/zUoMeOGjwr #nhs

New data on participation levels in #NHS democracy on @democraticaudit today https://t.co/ubv5MoJDyW

10 years after NHS Foundation Trusts were created, their democratic processes are failing https://t.co/klKQlugrsW