Elections to the NHS show that online voting is still in its infancy

The 1997-2010 Labour government introduced elections to certain authorities which oversee the National Health Service. Some of these elections now take place online, with ballots cast digitally. The Speaker’s Commission on Digital Democracy recommended last year that digital voting be expanded to UK general elections in order to help foster a climate of improved engagement. Here, Richard Berry shows that the availability of the option to vote online hasn’t led to high turnouts for NHS elections, but that this doesn’t preclude the possibility of it doing for general elections.

Credit: Birmingham Eastside, CC BY 2.0

Calls for the introduction of e-voting in UK elections have been growing louder in recent years. The Speaker’s Commission on Digital Democracy said the option to vote online should be available to all electors by the time of the 2020 general election. It doesn’t appear likely that the government will prioritise the change in this timeframe, although it has taken steps in that direction, particularly with the recent introduction of online voter registration.

Few democracies have so far introduced online voting for regular elections, with Estonia the most notable example. Much closer to home, e-voting is widely used in NHS elections, specifically for the election of governors of Foundation Trusts. Although run privately, these elections are in effect choosing senior representatives at major public agencies responsible for billions of pounds of taxpayers’ money, and therefore provide in important test of this reform. E-voting is not universally available, with many NHS trusts still relying solely on their more traditional method of postal voting. But its introduction means that NHS elections are, technologically speaking, far ahead of regular public elections in the UK.

As part of the Health Election Data project, I have assessed the popularity of e-voting at NHS elections held during 2015. Elections in 55 constituencies were included in this assessment, with a further 47 ‘offline’ elections used for comparison. Overall, the findings suggest that while there is slightly higher level of turnout at elections offering e-voting, only a minority of voters prefer to use this method.

Overall turnout impact

The turnout effect of e-voting – perhaps the key measure of interest to political reformers – appears to be marginal. In the NHS elections taking place in 2015 that I examined, the overall turnout at those offering e-voting was 17.1%. At elections where voters could not vote online, it was 16.0%. In an era of declining electoral turnout, this might be considered a small but significant difference. But it is impossible to ascribe the higher turnout to e-voting alone, without further data demonstrating its impact over a number of years.

Proportion of votes cast online

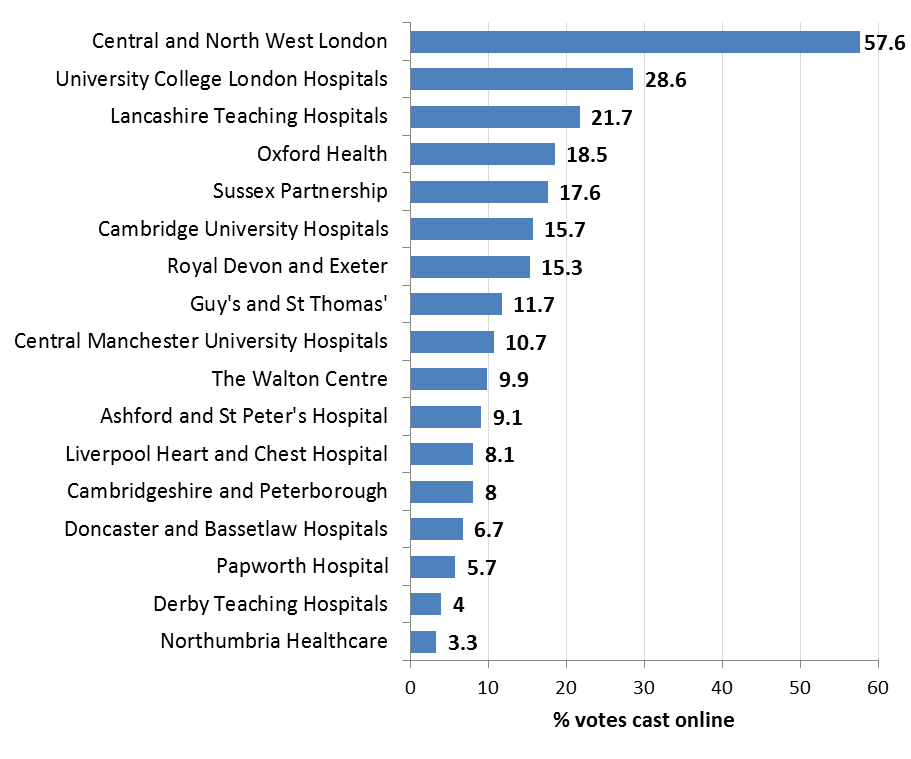

In the 55 elections offering the option of e-voting, the proportion of votes cast online was 12.6%. At just one in eight voters, this seems a relatively low proportion. This overall figures masks significant variation between trusts. At the Central and North West London NHS Foundation Trust, 58% of votes were cast online. At Northumbria Healthcare, it was just 3%.

Figure 1: Percentage of votes cast online at NHS governor elections by trust, 2015

The figures for individual trusts mask further variation within trusts. At Liverpool Heart and Chest Hospital NHS Foundation Trust, for instance, 28% of votes were cast online in one constituency, compared to just 5% in another.

Types of constituency

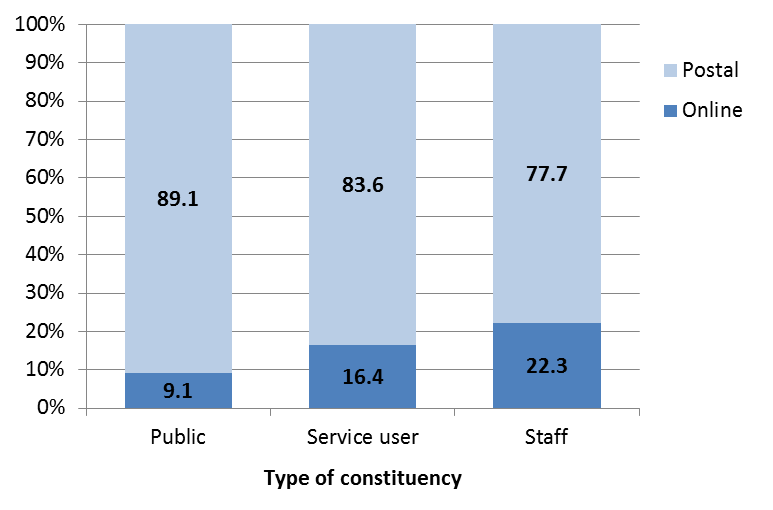

There appears to be a difference in take-up of e-voting among different types of voter at NHS elections. Most trusts elect governors for several types of constituency – general public, service users and trust staff. The 2015 election data suggests that trust staff are much more likely to vote online that members of the public, as shown below.

Figure 2: Percentage of votes cast online at NHS governor elections by constituency type, 2015

We can speculate at the reasons for this difference. Perhaps NHS staff are much more accustomed to interacting with their trust online than the public are, and voting in governor elections is a natural extension of this. For instance, staff may well have received notification of the opportunity to vote through an intranet system, while most ordinary members are notified by post.

Conclusions

When considering what these findings mean for the prospects of further online voting in the UK, some qualifications have to be made. Most importantly, comparison between NHS elections and other forms of public election is muddied by the fact that NHS elections were already all-postal affairs, before the introduction of e-voting at some trusts. Postal voting has been shown to increase election turnout because it is more convenient for voters than asking them to travel to a specific polling station on election day.

Therefore, the opportunity to participate online does not make as large a difference to voters at NHS elections as it would do at other elections, because a fairly convenient form of voting is already the norm. In practical terms, voters will receive a ballot paper in the post in the same envelope as they receive instructions for e-voting. It may well seem more convenient for the voters to simply fill in the ballot paper in their hands than logging on to vote online, especially when they know they can post their ballot back at their own convenience.

Even taking this into account, those in favour of e-voting will probably still be disappointed to see fairly low levels of online participation at NHS elections. This does not necessarily mean e-voting is not worth introducing. If security concerns can be addressed, any opportunity to make voting more accessible to the public should be explored. It may well be that e-voting only appeals to a minority of voters for the foreseeable future, but still forms part of a wider package of reform aimed at encouraging greater political engagement.

—

Note: this post represents the views of the author and not those of Democratic Audit or the London School of Economics. Please read our comments policy before posting.

—

Richard Berry is a Research Associate at Democratic Audit. He is also a scrutiny manager for the London Assembly and runs the Health Election Data project at healthelections.uk. View his research at richardjberry.com or find him on Twitter @richard3berry.

Richard Berry is a Research Associate at Democratic Audit. He is also a scrutiny manager for the London Assembly and runs the Health Election Data project at healthelections.uk. View his research at richardjberry.com or find him on Twitter @richard3berry.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Elections to the NHS show that online voting is still in its infancy https://t.co/tJ7t2wIbW0

Elections to the NHS show that online voting is still in its infancy https://t.co/JY9gyzKhll

more evidence that #onlinevoting doesn’t increase turnout https://t.co/U04ih197D2

Elections to the NHS show that online voting is still in its infancy https://t.co/oVQwh2QN8z

Foundation Trust elections may be very bad predictors of other public elections, because the demographics of FT memberships are often highly skewed. Have you been able to make any demographic analysis, particularly by age? Online voting may make a bigger difference amongst a nationally representative electorate.

“availability of the option to vote online hasn’t led to high turnouts” Surprise? NOT!

https://t.co/DKDvAdA2Hy

Elections to the NHS show that online voting is still in its infancy https://t.co/NmdQSCFOQg

[…] Richard Berry writes: […]

My research on use of online voting at NHS trust governor elections https://t.co/QvVuwocweH

Elections to the #NHS show that #onlinevoting is still in its infancy, writes @richard3berry https://t.co/7qxzA2lzc9

I am politically aware but did not even know about NHS elections. No wonder the turnout is only 1 in 6 people.

See @democraticaudit article from @richard3berry on the infancy of #evoting in the #NHS; its potential & limitations https://t.co/tYZG2roOZC

Perhaps the major lesson to learn from this is that we have a “secret democracy” – NHS governors elections?

Are these a secret that is only available to some subgroup of the “internet-arti”?

This has to breed suspicion before we even start to examine all the issues about personation or coercion in online elections!

Elections to the NHS show that online voting is still in its infancy https://t.co/2hk7cJCM4U https://t.co/JNyF7DL9DX