Debate part 1: should adding ‘None of the Above’ to ballot papers be a priority for UK political reformers?

Is adding ‘None of the Above’ to ballot papers a good idea, and would it make any real difference? Democratic Audit has carried pieces from firm advocates and sceptics of the proposal. Here, Emma Rome (an advocate of the reform), and Richard Berry debate its merits in the form of an exchange of emails, which we publish below.

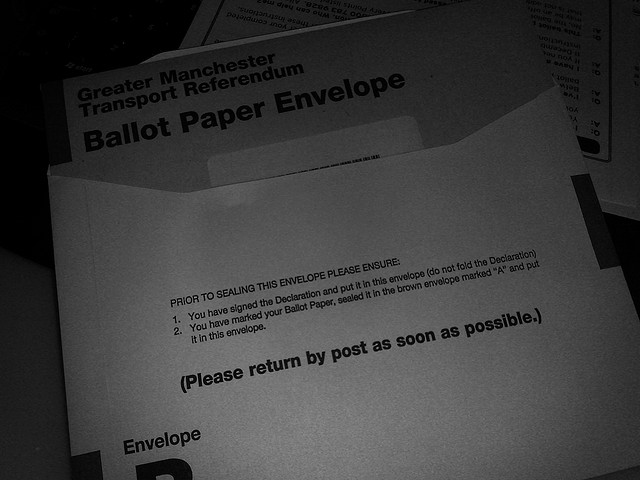

Credit: Mjmall (tiggy), CC BY 2.0

Dear Richard,

Adding ‘None of the Above’ (NOTA) to ballot papers should be a priority, since the consent of the governed means little when the ability to withhold consent (as opposed to merely abstaining or intentionally spoiling a ballot, which is officially considered to be either disinterest or failure to follow instructions). Without the ability to withhold consent, there is a democratic deficit, which needs to be addressed. However, NOTA, as I originally proposed on my blog isn’t intended to be a quick fix. In the short term, I would actually expect it to make little difference. Instead, I would expect it to trigger a slower shift, but one ultimately great than could be achieved by PR, party primaries, or a lower financial threshold for standing for election. NOTA is intended to organically shift MP attitudes towards truly representing their voters; no MP wants to be known for having been just barely popular than someone – anyone – else. And the best way they can avoid that is by being responsive to the voters.

Party primaries still leave existing parties in the same position where they can manoeuvre to exclude broader points of view. The USA has party primaries, yet, according to Lenin,

“[…] representative democracy had simply been used to give the illusion of democracy while maintaining the dictatorship of the bourgeoisie; describing the U.S. representative democratic system, he described the ‘spectacular and meaningless duels between two bourgeois parties’, both of whom were led by ‘astute multimillionaires’ who exploited the American proletariat.”

He was writing about USA of 100 years ago, but given the similarities of the two main parties in the UK today (pro-Europe, pro-TTIP, pro-austerity, pro-military intervention, pro-steadily rising housing costs), he might as well have been writing about modern Britain. Party primaries don’t give any effective ability to withhold consent. They don’t give parties any reason to be responsive to anyone who is not a paid-up party member.

Were I a Mauve Party member, the Magenta Party would not be interested in my views on who should lead their party; the reverse is also true. Indeed, opening up such primaries to non-party members would open the door to voting for weak candidates to ruin your opposing party’s chances. It’s simply not possible for primary election voting to be open to non-party-members.

Regards,

Emma

Dear Emma,

I appreciate you are not suggesting NOTA would be a quick fix. Indeed, there are no quick fixes available when it comes to addressing fundamental weaknesses in UK democracy. Yet I fail to see any mechanism by which NOTA will achieve the desired effect, which you describe as “organically shift[ing] MP’s attitudes towards truly representing their voters.”

As an aside, I would say this is an unfair dismissal of those many MPs who do seek to represent voters to the best of their abilities. But the crucial flaw in the argument is that no solid reason is given for why MPs’ or parties’ attitudes change significantly as a result of NOTA being on ballot papers. I can envisage circumstances where NOTA could be very useful – for instance, it could help voters boot out a corrupt incumbent who has been re-selected by their party. For that reason alone it is worth considering. However, that is a rare occurrence.

As for primaries, we could have a whole separate debate on that topic. The United States is just one of many countries using primaries, and we shouldn’t make the mistake of attributing the problems of their money-dominated system to the existence of primaries. Primary elections, when opened up to non-party members in the UK, have been a great success.

Regards,

Richard

Dear Richard,

I note that NOTA would not be a quick fix for the same reason that PR not be a quick fix. I would not expect either of these to create anything resembling a new status quo in less than two election cycles, and possibly more. In the first election after the reform’s implementation, party strategists would make plans based on old voting patterns, and voters will be a combination of confused by the new system and keep to the same “tactical” voting pattern they always have (or just according to how their folks have always voted), or voting sincerely based on their personal political views.

It is very likely that a significant fraction won’t recognise how best to use the new voting option(s) presented in either PR or NOTA (or both, were they implemented together). Additionally, a great many people who had never before voted are likely to vote (and some who previously voted may decide to abstain because they don’t understand the new system or disagree with it on a fundamental level), skewing party strategists’ plans further. In the second round, party strategists will respond to these changes in voter behaviour, whilst voters would very likely change their behaviour again in response to how they saw everyone change their behaviour in the first election after reform.

This change in behaviour based on an observation of how the reform would work is what I refer to as an organic shift – it grows out of behaviour in a dynamic manner. And this dynamic behaviour would affect MPs too. Just as an MP who is seriously challenged by an opposition candidate may choose to stand down (or may be asked to stand down by his local party), the same would apply if that MP were seriously challenged by the NOTA vote.

Just as wise MPs in marginal constituencies today listen to voters who support other parties (and MPs in very safe seats have been known to pay more attention to party policy than constituency views), an MP who was seriously challenged by the NOTA vote would reasonably be expected to pay closer attention to the needs of his constituents than one who wasn’t so challenged.

I note that you see NOTA as a way in which voters could boot out a corrupt (or merely unpopular) incumbent. While it is true that it could be used as a rallying banner so that, for example in a three-way constituency, the two trailing parties could call on their supporters to unite under NOTA to force the lead party out, that isn’t its main strength. I would like to see the ability for voters to recall their MP via petition and force a by-election. Voter recall would be the best method for this to happen, because it could in principle happen at any point in the lifetime of any given parliament. The strength of NOTA is that it gives people who might otherwise not have a canddiate who represents their views the opportunity to continue to participate in an election and have their vote potentially make a real difference.

Regards,

Emma

—

Note: part two of this exchange will be published shortly. The views expressed here represent the views of the participants and not those of Democratic Audit UK or the LSE. Please read our comments policy before posting.

—

Richard Berry is a Research Associate at Democratic Audit and the LSE Public Policy Group. He is a scrutiny manager for the London Assembly and also runs the new Health Election Data website. View his research at richardjberry.com or find him on Twitter @richard3berry.

Richard Berry is a Research Associate at Democratic Audit and the LSE Public Policy Group. He is a scrutiny manager for the London Assembly and also runs the new Health Election Data website. View his research at richardjberry.com or find him on Twitter @richard3berry.

Emma Rome is a former teacher and independent liberal political blogger. She is a member of the Electoral Reform Society. Her blog can be found here.

Emma Rome is a former teacher and independent liberal political blogger. She is a member of the Electoral Reform Society. Her blog can be found here.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

[…] Two of my email debate with Mr Berry of Democratic Audit is now online. Part One was posted to that site […]

[…] Democratic Audit UK recently hosted part one of a debate between Emma Rome and Richard Berry on the pressing need – or otherwise – to add a ‘None of the Above’ option to UK ballot papers. Proponents argue that true democracy cannot exist without this option, whereas sceptics argue that the measure would have a marginal impact and that political reformers should have far greater priorities. Part one can be found here. […]

Re: “…no MP wants to be known for having been just barely popular than someone – anyone – else. And the best way they can avoid that is by being responsive to the voters.”

I’m not so sure that MPs go into office wanting to interact with the people in their constituency. They make a big effort to engage people, just prior to an election and then ramp back on their interactivity until the next time.

My sister made some effort to interact with David Mellor, and he just sent back standard letters.

https://t.co/unEIHpKByh I debate #noneoftheabove with @richard3berry

Debate part 1: should adding ‘None of the Above’ to ballot papers be a priority of UK politic… https://t.co/Kk3kgve18n https://t.co/pj4uCCfqpn

[…] I entered an email debate with Mr Berry of Democratic Audit. Part One of the debate is now […]

Primary elect.:Debate part1:should adding ‘None of the Above’ to ballot papers be a priority for UK polit. reformers? https://t.co/Uh9DOj9lwr

Debate part 1: should adding ‘None of the Above’ to ballot papers be a priority for UK political reformers? https://t.co/FbG6oFvixV

Mr. Berry’s question is rather disingenuous, the mechanism by which NOTA delivers changes is through the ballot box. It’s is not exactly obscure. What he is believes, though for some reason not making clear, is that the addition of NOTA will not change the voting behaviour of the electorate.

Does he have a point?

A symbolic or poorly implemented NOTA option could well not be taken up in large numbers; however a well implemented NOTA, with a good set of guidelines to manage the logistics of re-run election(s), from a single constituency upwards, would be far more attractive, once voters get used to having it on the ballot and see how it functions.

Voters deserve the opportunity to withhold their consent to be represented or governed as easily as giving their consent, and both options should be catered for in a system that calls its self a democracy.

At the very least we should acknowledge that our current system is not a democracy and it has very different characteristics to one. In our system sovereign power does not ever reside in the electorate, it resides in parliament and is welded by those who make it in there. We have an elected oligarchy, I think voters deserve to be told this truth so they can have the opportunity to decide if they want continue with such a system or change for a democratic one.

Let’s assume for a second that the priority of political reformers should be to address the perceived theoretical flaws of our democratic system – as yours is – rather than to give people practical and useful ways of influencing how we are governed…

Your version of NOTA does not give sovereign power to the electorate. By your own admission, you want the second-placed candidate to assume the vacant seat, where NOTA has won a constituency election. What is to stop the new Parliament with x number of second-placed candidates in it abolishing the NOTA option, possibly even declaring those second-placed candidates are allowed to serve a full term after all? Absolutely nothing.

Even if you change the model to say that the seat remains vacant until the subsequent by-election, rather than allowing the second-placed candidate to take it, the rest of the MPs could do it anyway.

What you need to avoid that is a constitution that is founded on popular consent and only amendable by a referendum. So that’s really where you should be focusing.

What you’ve done is identify a problem (the lack of popular consent) and decided that NOTA provides a solution. Whatever the merits of NOTA are – and there are some, as Emma argues forcefully – it doesn’t solve the problem you want it to solve.

None of this is a game, you should stop treating it as one.

Why is it you think that NOTA does not give more power and influence to voters? Without a NOTA option voters can only choose between candidates based on their relative merits, with the inclusion of a well implemented NOTA option, it allows them to choose dependent on a candidate or party’s ability or willingness to represent the voter’s interests. Its a massive shift.

It also makes negative campaigning tactically useless, as the more negative campaigning there is, the more it promotes the use of NOTA as an option.

What you are doing is pretending that my concerns are theoretical, no they are practical.

However to deal with your theoretical objections. The UK has signed and ratified the ICCPR and no act of parliament can overturn it, as far as I understand. Article 25b states that (I paraphrase for convinience) that elections must guarantee the free expression of the will of the electorate. The only way this can be guaranteed is if they obtain voter consent (and that can only happen if the commensurate ability to withhold consent exists). Am I wrong?.

Can the free expression of the electorate be guaranteed without obtaining their consent?

NOTA is there for that purpose, to bring consent into the election process.

So you see Richard, parliament cannot take NOTA away or they will be in breach of the ICCPR.

I want to make an amendment

Can the free expression of the will of the electorate be guaranteed without obtaining their consent?

I missed out ‘the will of the’ in my last reply, it makes a big difference in my opinion.

It’s certainly true that any majority government could repeal almost any law at any time. But to argue against a reform on the basis that it could later be repealed is to make an argument for total apathy in all campaigns of a political nature — because any majority government can repeal any law.

I think he is throwing up objections for their own sake rather than a serious attempt at debate, or his understanding of democracy is inadequate.

Its clear he doesn’t really understand NOTA as a concept.

Democracy is dependent on the consent of the governed, and that’s what NOTA does, it ensures whoever is in power is there by the consent of the voters. Sovereign power does not reside in parliament but resides in the electorate who let their representatives exercise their power on their behalf after giving their consent.

The technicalities of it are not that important IMO.

Can anyone guarantee a healthy well functioning democracy without a reliable measure of voter consent? Isn’t it essential to have a reliable indicator of voter disaffection and discontent? It cannot be achieved without an well implemented NOTA option, as far as I can see anyway.

Should we have ‘none of the above’ on ballot papers? My debate with @politicalemma on the pros and cons https://t.co/s6XMhhlX6u

Part One of my debate with @richard3berry is now online. https://t.co/cSp3Vjq0Du @electoralreform #notavote #notauk @katieghose @nick_clegg

I originally posted the following in response to a video on Youtube about this subject, which can be found at youtu.be/QdiG9tCq-BU.

I believe that if we have true democracy, then we should be able to reject all options on offer and tell the politicians to go away and come up with better alternatives, so I strongly support this proposal.

If all of the candidates, or their parties, are rejected by the electorate, then they should fail at the ballot box, as opposed to us voting for the ‘least worst option’. Currently, even if 100% of the ballot papers are spoiled, someone wins, because lots will be drawn to determine a winner (in the event of a tie).

With regard to the re-run, I would support that if all the candidates from the first ballot are barred from any such. They must be all new candidates. Otherwise, you are effectively saying that the first ballot was a waste of time, like a mistrial, and this would not be respecting the result of the ballot that rejected them all in the first place.

The re-run with all new candidates may give a different result if it is the original candidates that were the problem. If however the problem is the lack of any acceptable party, or party policies, then the constituency should be able to continue to reject all of the above, by voting ‘NOTA’.

In the event of a continuing vote for ‘NOTA’ (I don’t see the need for a 2nd re-run), then there should not be elections ad nauseum until someone wins, nor lots drawn. The constituency should be able to return no candidate and no MP therefore.

As there will be no MP, the constituents should therefore be represented collectively by The Government. These constituents should be able to deal directly with Ministers and The Government over their issues that they might otherwise refer to their MP.

If the failure of the political system results in a ‘none of the above’ scenario, then it is the politicians that should take the responsibility for filling the gap created by their failure to offer an acceptable candidate, or candidates, or policies.

In theory, this scenario could be repeated across the country and if that should occur, then we should be able to effectively say that the country has no confidence on any of the above. This would force all the parties to come-up with acceptable policies.

This nationwide scenario would be extremely unlikely, but nevertheless possible. It should be regarded by the political parties as a deterrent against complacency, doing what they like or even forming political cabals, where effectively it does not matter who wins, as you will get more-or-less the same sort of candidates and policies.

“None of the above” would give true democratic power back to the electorate.

Debate part 1: should adding ‘None of the Above’ to ballot papers be a priority of UK political reformers? https://t.co/OV23YNW8Zr