Requiring voter ID in British elections suggests the government is adopting US ‘voter suppression’ tactics

This week’s Queen’s Speech revived proposals to introduce photographic ID requirements for voting in British elections. The Democratic Audit team assess the available evidence on the likely consequence of such a measure, and consider whether the legislation tackles the right priorities for improving our elections on which there is consensus, or suggests moves to enhance Tory election chances via excluding voters presumed unfavourable to them.

Picture: Kodak Views/(CC BY 2.0) licence

The government has announced plans to introduce compulsory photographic ID for all voters in UK general elections as the centrepiece of a new electoral integrity bill. This would require all voters for UK parliamentary elections in Great Britain and for English local elections to show an ‘approved form of photographic ID’, usually a driving licence or passport, at the polling station. This is already required for Northern Ireland voters, where you can obtain a free ID card, which would under these proposals also be available in the rest of the UK. It would not apply to elections to the Welsh Assembly and Scottish Parliament, nor for local elections in these nations.

This measure initially formed part of a package of reforms that Eric Pickles proposed in a 2016 report on electoral integrity, and a commitment to introduce some form of voter ID requirement was included in the Conservative Party’s 2017 manifesto. Since then voter ID trials that have taken place in several areas during the 2018 and 2019 English council elections. Requiring photographic ID represents the most stringent requirement of the variations piloted: the others included the choice of showing two forms of non-photographic ID, or simply producing your polling card.

Voter ID: is there a problem?

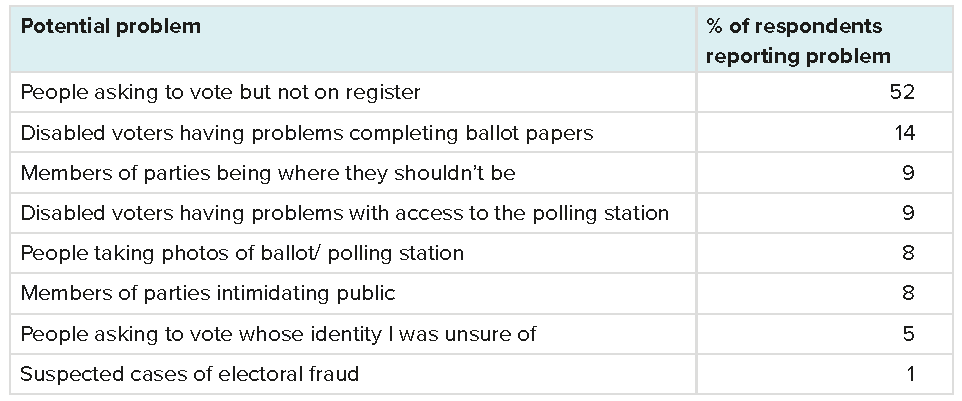

The first question the proposal raises is: why? The number of reported cases of electoral fraud from personation at the polling station are exceedingly low. Just one case was prosecuted in 2017, and none in 2018. The available evidence suggests it is rare. As Figure 1 shows, it was the lowest-rated concern of poll workers in a 2018 survey, while a far greater reported problem was potential voters turning up at a polling station, and being turned away for not being on the register there. The Electoral Commission reported a small uptick in confidence in the integrity of the voting system in pilot areas, though starting from a high base, and they caution that, as with the pilots overall, these are not representative samples of the whole of Great Britain.

So, what were the consequences of the trials in terms of turnout? As Michela Palese points out, of 2,000 voters initially turned away for not having ID in 2019, 750 did not return to vote. Though the percentages were low in both trials in 2018 and 2019 (the highest percentage of total voters who did not return stands at 0.7%), the number is significant enough to be of concern. The effect for general elections would not necessarily be the same as for lower-turnout local elections, and it would be enough potentially to bring into question many constituency results, considering marginal seats can be won by just a handful of votes.

Figure 1: Problems experienced by poll workers at the English local elections 2018

Source: Clark and James, 2018 (as quoted in Toby S James, chapter 2.4 in The UK’s Changing Democracy: the 2018 Democratic Audit). Note: % exceeds 100 as workers can report more than one problem.

The Electoral Commission has noted that as many as 3.5 million voters may not have photo ID, and that ownership of ID, and awareness of the requirements for the pilots, can differ by socioeconomic groups, with citizens from ethnic minorities in particular potentially disadvantaged. According to the Electoral Commission, over the two sets of pilots, the areas taking part, are ‘not fully representative, in socio-demographic terms, of many areas of Great Britain’. No inner-city urban areas have been piloted, and, though the amount of available evidence is slim, in the two pilot wards with a higher proportion of Asian-background voters, more people were turned away at the polling station for not having ID. Hence Jeremy Corbyn has already denounced them as ‘clearly discriminatory’.

So, there are considerable concerns that the negative impact of voter ID laws on restricting access to voting by those without ID will far outweigh any potential impact on countering electoral fraud, or improving trust in the system. There is likely to be a strong partisan differential in the impacts of the change, with Labour losing out markedly but the Conservatives less so – another reason for Corbyn’s concern. In this sense the move seems of a piece with the kind of ‘voter suppression’ tactics systematically pursued by US Republicans for excluding voters unfavourable to them from the polls.

Other proposals: postal voting and regulating online campaigns

While the headline proposal was voter ID, the government’s plans do address some other concerns with how our elections are run, which has received less attention. These include the second and fourth most-cited problems indicated in Figure 1: that of voters with disabilities having difficulties voting. The new bill would allow carers to assist voters at polling stations, and place a requirement on returning officers to improve accessibility.

In recent years, one concern that has been raised by politicians and voters relates to the scope for electoral fraud through postal voting, which is available on request to all voters in England, Wales and Scotland. Again, the cases prosecuted are extremely low, though there remain concerns that postal votes can create loopholes that can easily be exploited in some communities. The legislation proposed in this Queen’s Speech includes tightening the rules on postal vote collection, and would require re-registration for postal votes every three years.

The government also commits to introducing digital imprints for online campaign material to extend the rules on identifying who has produced and paid for an advert that apply to printed materials to online adverts. This is something the Electoral Commission, Electoral Reform Society, MPs and many democracy campaigners have been calling for, particularly in the wake of the 2016 EU referendum.

The wrong priorities for fixing our electoral laws

Given the exceedingly low numbers of cases of voter personation, the question remains whether voter ID in particular is the right legislative priority for improving elections – and whether further piecemeal reform introduced without any cross-party consensus is the right approach at all. Earlier this year, the Commons’ Public Administration and Constitutional Affairs Committee asked for evidence on reforming Electoral Law, noting that many rules dated back to the nineteenth century, and had been updated through numerous separate pieces of legislation, creating a fragmented and confusing set of laws. Proposals from the Law Commission in 2016 for systematic review and simplification had not been acted on. Much of the academic evidence which the committee received reiterated the view that consolidation, wholesale modernisation and simplification, particularly in the context of devolution and increased digital campaigning, was a priority over voter ID laws, which could add another layer of administrative complication for little benefit.

Given levels of voter registration and turnout remain key concerns, measures that encourage voting should take priority. Toby James and Alistair Clark have set out some proposals for encouraging greater participation in their report Missing Millions Still Missing. They include a single national electoral website, where voters could check they were registered. Voters being unable to confirm they were correctly registered, and a lack of resources, were contributing factors to many EU citizens being unable to vote in 2019’s European Parliament elections. There is also concern that cuts to local government funding mean electoral services are already stretched and voter-engagement work has been cut back, which would be essential for informing voters of any new voter ID requirements.

Reforming elections or rigging the micro-institutions?

With the government lacking any sort of parliamentary majority, the likelihood of this new electoral integrity bill progressing through this parliament is exceedingly slim. Voter ID laws – or any other electoral reforms – will not be introduced prior to any general election in 2019 or early 2020. Their appearance in the Queen’s Speech does, however, give some indication of Conservative priorities for democratic reform in their next election manifesto. What is as yet unclear is whether they will revive another proposed change in the 2017 Conservative manifesto to extend voting rights to overseas electors for life, a measure that fell at a late hurdle in the last parliamentary session. It is all but guaranteed though that they will continue to block any attempt to extend the franchise to 16- and 17-year olds, in contrast to all other main parties and the administrations in Scotland and Wales (where votes at 16 will be introduced for the next Assembly elections).

This too looks overtly partisan in its intentions. Voter ID requirements and only selective support of extending the franchise might be thought to fit easily into the Johnson administration’s developing record of fully exploiting any micro-institutional levers to hand for party advantage, putting the UK on a downwards slope that can rapidly lead to significant ‘democratic backsliding’. It will be up to voters in the general election to endorse or prevent future moves on these lines.

Sections of this piece were originally published as part of the LSE British Politics and Policy blog’s article, Empty Bills: The Queen’s Speech was an odd contribution to solving the UK’s problems.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Most European countries require photo ID to vote, which is provided free as will be the case here. Perhaps you could explain why it’s so different for the UK to be like other democracies?