How private financial donations affect party extremism

What is the impact of private donors on a party’s policy platform? Using a new database of 45 parties in 9 OECD countries between 1996 and 2013, Andrey Tomashevskiy finds that the effect of donations is significant, and that parties which receive a greater percentage of their income from private donors tend to adopt more extreme positions on socio-cultural issues.

Photo by Vitaly Taranov on Unsplash

Why do parties take ideologically extreme positions? Ideological extremism may have important consequences for democratic politics, resulting in legislative gridlock, political polarisation and increased potential for societal conflict. While parties are typically thought to respond to the preferences of the general voting public, I argue that parties may be more responsive to the ideological preferences of private donors, especially when parties are more reliant on private donations, and the financial constraints faced by political parties may have important consequences for political position-taking. In recent research, I examine this relationship with new data on private donations to 45 parties in 9 OECD countries.

While private donations to political parties play roles of varying importance across developed Western democracies, most parties depend on donations for some portion of their income. To ensure a continuing stream of income, parties must take donor preferences into account when selecting policy positions. Donors give money for both ideological and pragmatic reasons: donations increase the likelihood that a party will be elected to office while also ensuring an ideological orientation consistent with donor preferences. A donation is an investment in the party as well as a way for donors to exercise voice within a party structure. When private contributions represent a significant component of overall party income, party leaders must take donor preferences more seriously. These preferences are distinct from the average voter: research shows that donors are more likely to have less centrist, more extreme ideological preferences. While parties must balance the political preferences of the public, candidates, donors and more moderate party supporters, donors may have more influence in ensuring their preferences are reflected in policy platforms when parties are reliant on private donations to finance their activities. Since donors tend to have more extreme policy preferences, greater reliance on private donations provides an incentive for parties to adopt more extreme policy platforms.

However, this strategy also involves costs since parties risk alienating the general voting public by adopting policy stances that are too extreme. In polities where political financing depends on electoral performance, parties may also risk losing access to non-donor funding if centrist voters are alienated by policy positions adopted to satisfy donors. Party leaders may solve this dilemma by selecting a mix of policy stances across a variety of issues to appease the interests of more ideologically extreme donors, while also ensuring continued support by ideologically centrist voters. This policy mix may involve varying stances across principled and pragmatic issues. Party leaders may balance the extremist demands of donors on value-based, principled issues, such as socio-cultural issues, by adopting more moderate positions on pragmatic issues, such as economic issues. If donors are primarily motivated by ideological and socio-cultural goals, then the more a party relies on private funds, the more likely it is to take non-centrist ideological positions on principled (rather than pragmatic) issues.

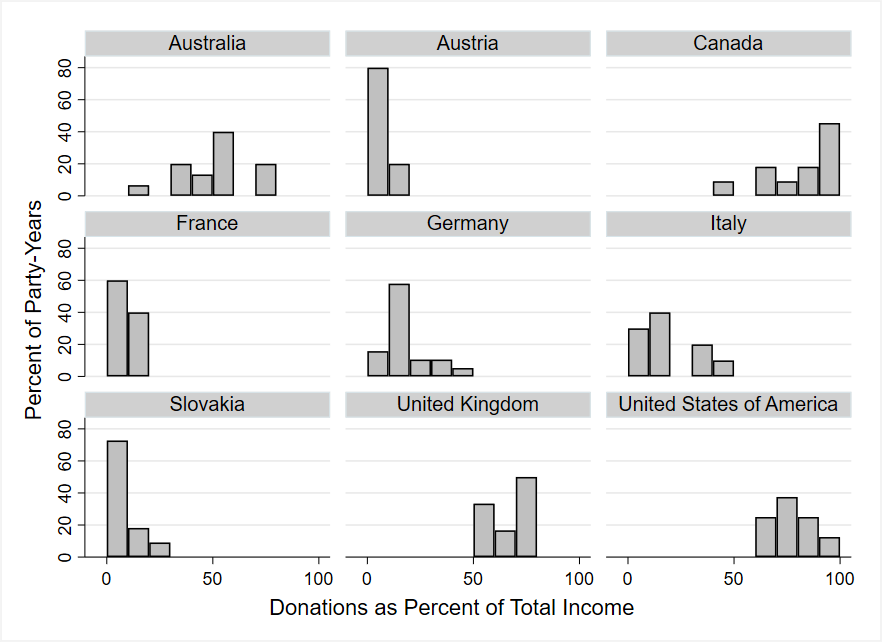

To test these hypotheses, I collected data on private contributions as a percentage of total party income for 45 parties in 9 OECD countries. Using annual balance sheets submitted to central government bodies, I collected information on party income and private, non-member, non-government contributions. Campaign finance regulations vary widely across countries, and only a small number of them require political parties to provide detailed annual financial data on the source of the donation. This sets limits on any effort to collect data on political contributions across countries and over time. Nevertheless, the data assembled for this study are the most comprehensive cross-national data collected to date about private donations to parties. Although the countries included in this sample are driven by data availability, the included countries represent a wide variety of electoral and party finance institutions. Thus, the sample includes majoritarian (US, Canada, UK, France), proportional (Austria, Slovakia) and mixed-member (Germany, Italy) electoral systems. Parties in this sample also vary widely in their dependence on private funds: parties in the US and Canada derive more than 90% of their income from private donations, while parties in Austria receive less than 20% of their income from private funds. Figure 1 presents the distribution of donations as a percentage of party income by country. Since the included countries are all developed OECD countries, the effects identified for this sample are likely to hold for developed democracies that are not included in this analysis.

Figure 1: Distribution of private donations by country

I find support for the notion that parties adopt positions further from the ideological centre when private donations account for a higher percentage of a party’s total income. This effect persists for socio-cultural issues but not for pragmatic economic issues. These effects are substantively large: the socio-cultural extremism of a party increases by 8 points on a left-right ideological scale as donations increase from low to high (i.e. from the 25th to 75th percentile value). Substantively, an 8-point change on the ideological scale is equivalent to the difference in socio-cultural values between the anti-immigrant, radical right-wing Austrian Freedom Party and the conservative Austrian Peoples’ Party.

Additional analyses also support the argument that it is specifically donor influence driving this relationship. I use information on the restrictiveness of party finance laws to examine the impact of private donations. If donors are less influential in polities with more restrictive party finance laws that limit party spending and private donations, parties will have less of an incentive to respond to donor demands. This pattern is supported by the data: private donations have no impact on party positions in countries with more restrictive party finance rules. The relationship between extremism and donations is primarily a phenomenon in countries where private donations and party spending are unrestricted and donors are able to exercise more influence.

These findings suggest an important feature of modern democratic politics: party policy platforms are in part driven by the rising influence of donors. As parties become more dependent on private donations, their policy platforms are more likely to reflect donor preferences, which may be ideologically more extreme compared to the policy preferences of the general voting public. Unlimited donor influence may undermine democratic effectiveness and force parties to move away from the ideological centre to satisfy donor demands. To limit donor influence, more restrictive party finance laws may be necessary. As my findings show, when donor influence is limited by regulations on party spending, limits on donation amounts, or by public financing of parties, the link between private donations and party policy platforms disappears.

This article gives the views of the author, and not the position Democratic Audit. It draws on the author’s article ‘Does private money increase party extremism?’ recently published in the Journal of Elections, Public Opinion and Parties.

About the author

Andrey Tomashevskiy is an Assistant Professor of Political Science at Rutgers University. His research investigates the politics of international investment, political finance, and corruption.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.