Selfies, policies or votes? How politicians can campaign effectively on Instagram

Twitter and Facebook have become crucial arenas for political competition, but what about Instagram? In new research, Stuart Turnbull-Dugarte assesses how parties in Spain have used the image-based social media platform and finds that political newcomers like Podemos and Ciudadanos are most effective at engaging voters, particularly when they focus on political leaders and mobilising supporters, but that policy communication is less effective.

Photo by Gian Cescon on Unsplash

In politics, social media matters. Given the historical demise of newspaper readership and its replacement by social media as the main source of news for an increasing percentage of the electorate, social media platforms can be effective tools for political communication and electioneering. While a solid body of literature has assessed the use and political potential of Twitter and Facebook, we still know very little about how political parties use Instagram in their election campaigns. It’s a cliché, but it really is the case that a picture speaks a thousand words, especially when it comes to political communication. Take, for example, communicating a candidate’s stance on a particular policy concern like LGB(T) rights: one shared photograph of a candidate at a Pride march is much more likely to communicate their support for LGB(T) rights than a tweet to the same effect could. There is therefore clear political potential in a photo-sharing app like Instagram.

Given, then, that Instagram has surpassed Twitter to become the second-most widely used social media platform after Facebook, we can expect parties to make sure they are present and active on the same platforms as their voters. There are three central questions here: do parties use Instagram? What strategic purpose does their Instagram use suggest? And, what features of their communications on the platform generate the most engagement amongst users?

To answer these questions, in recent research I analysed the use of Instagram by political parties in Spain during the 2015 and 2016 general elections. A dataset of 221 Instagram posts was manually coded, including all posts from the accounts of the four main political parties in Spain: the centre-left Partido Socialists Obrera Español (PSOE: Spanish Workers’ Party), the centre-right Partido Popular (PP: Popular Party) as well as the two new parties – the leftist Podemos (We Can) and the centrist Ciudadanos (Citizens).

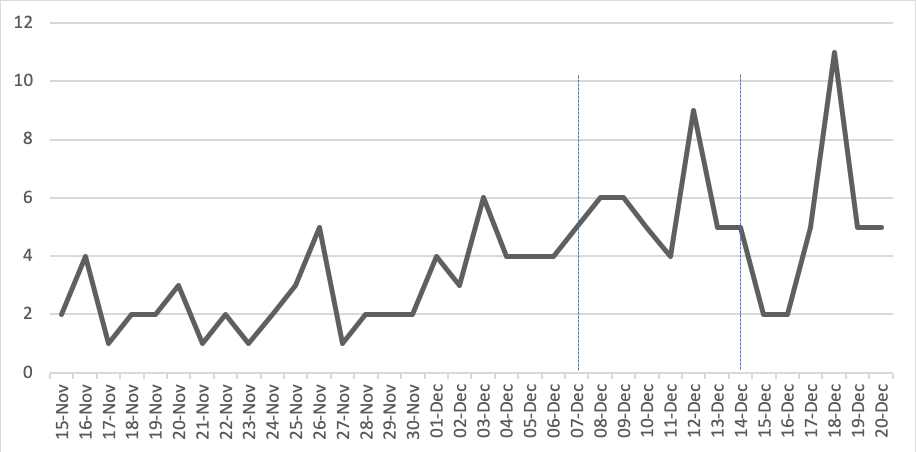

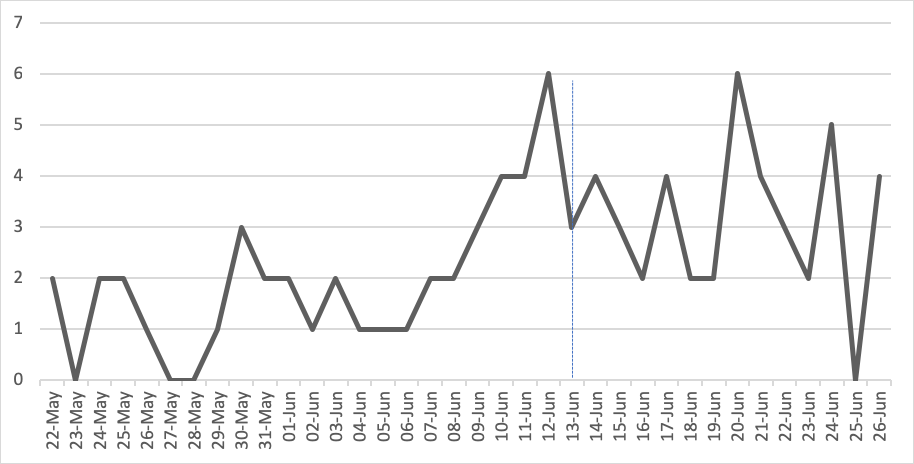

In the first instance the analysis showed that there was a clear difference in the extent to which parties were willing to use Instagram during the election campaign. The two emerging parties, Ciudadanos and Podemos, together dominated, amounting to 68% of posts made during the 2015 election period and 79% of the publications in the 2016 campaign. The political old guard did not seem to view Instagram as an important tool for electioneering. This is consistent with previous work that underlines the ability of political entrepreneurs to better adapt to new media environments. Overall, though, Instagram use was relatively low, averaging around four posts per day across the entire sample.

Figure 1: Partisan Instagram Posts (Spain, 2015 election)

Note: Dotted lines mark date of the televised debates.

Figure 2: Partisan Instagram Posts (Spain, 2016 election)

Note: Dotted lines mark date of the televised debates.

The PP only posted seven times during the four weeks leading up to the 2015 election and the PSOE published only two(!) posts during the same time frame before 2016 polling day. While Instagram was reported to be the second-most widely used social media application amongst young people, and social media represented the main source of campaign data for 37% of this demographic, parties from the old bloc (who received the lowest share of votes amongst young people) were apparently not interested in reaching out to these voters via one of the platforms they are most likely to use for campaign information.

Vote seeking post; Source: PSOE via Instagram

In coding the content of the main parties’ posts, I assessed three main characteristics: promotion of the main candidate; description of the party position on policy; and mobilisation of supporters to vote. There is substantial variation in the strategic focus of the parties. The party most likely to promote their main candidate was Ciudadanos, with the party’s leader, Albert Rivera, appearing in 86% of all of the party’s posts. This is unsurprising given that Rivera was the candidate assessed most favourably by the electorate at the time. Moreover, attaching a personalised image to the party brand is necessary for a new party, since there exists no bank of loyal voters who know and trust what the party name represents beyond an individual leader. None of the other parties actively sought to promote the image of their leader and actually reduced the number of posts depicting their leader between the two elections. This coincides with the collapse of positive assessments of the candidates for the presidency when they were unable to form a government after the first round of elections.

Policy broadcasting post; Source: Podemos via Instagram

None of the parties focused on promoting party policies, with only 8.9% and 4.7% of all posts made in 2015 and 2016 respectively making explicit statements about policy positions. While a greater amount of posts focused on mobilising voters (49% in 2015; 41% in 2016), mobilising messages on average appeared in the minority of publications. The exception here is that of Podemos, which dedicated around 62% of its communications to drive turnout and mobilise their followers (i.e. their potential voters). The focus on mobilisation in Podemos’ communication strategy echoes how they used other social media platforms. The party developed out of the Indignados/15-M movement in opposition to austerity, which was successful because of its ability to utilise social media platforms to organise and mobilise its supporters. There is, then, an observable strategic preference in Instagram use amongst the partisan underdogs, but the same cannot be concluded of the two parties from the old bloc. Neither the PSOE nor the PP made consistent or observably strategic use of Instagram in either 2015 or 2016. However, PP doubled the number of posts made in the second election, which suggests the party was beginning to realise the potential it had for political communication.

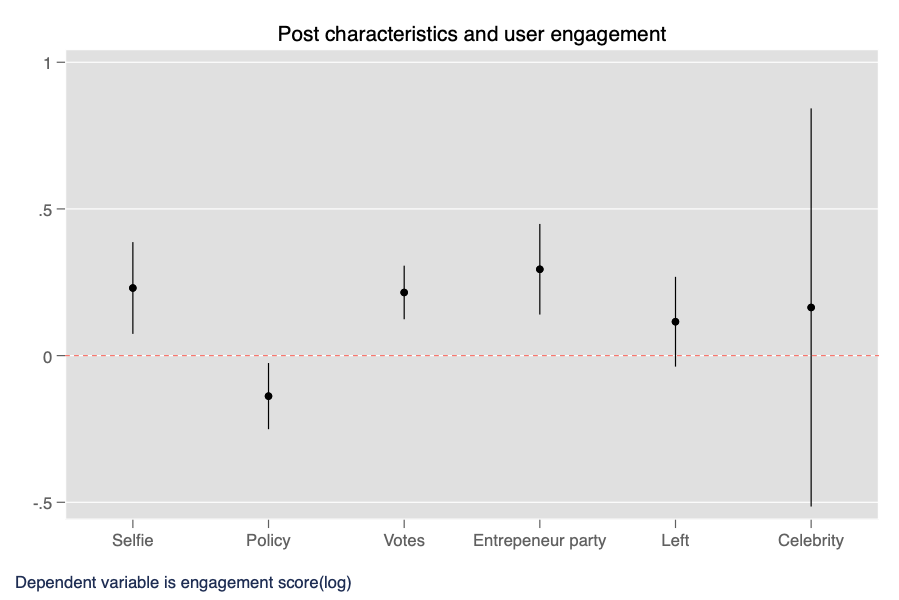

Turning to the third question to judge what is effective for parties on Instagram, an OLS regression estimation measured the levels of engagement of Instagram users with different types of posts. Figure 3 shows the impact of different features on the level of user engagement with partisan posts. Party material that tends to focus on promoting the main candidate (Selfie) and those that attempt to mobilise voters (Votes) increase engagement whilst those that focus on promoting a party’s position (Policy) have a negative effect. Interestingly, having celebrity endorsements does little to alter how users respond to parties’ communications.

Figure 3: Instagram post characteristics and user engagement

When it comes to understanding how parties use Instagram and the success of their different tactics, the case of Spain suggests that above all else political virginity matters. Those parties who emerged on the national political arena to compete in their first general election in 2015 were the most active users of the platform, the most popular and activated the greater amount of engagement with their users. However, posts that promoted policy proposals failed to create much buzz, and the findings indicate that parties would do better to concentrate their efforts on other social media messages. Posts that focus on promoting the party leader seem to be effective.

Of note in the UK is that at the time of data collection (April 2017) none of the main political parties – Conservatives, Labour, Liberal Democrats – had links to their official Instagram profiles embedded on the party website. An observation that might signal the growing importance of Instagram as a political tool is that they do now.

This post represents the views of the author and not those of Democratic Audit. It is based on the author’s paper, ‘Selfies, Policies or Votes? Political Party Use of Instagram in the 2015 and 2016 Spanish General Elections’ available open access in the journal Social Media and Society.

About the author

Stuart Turnbull-Dugarte is a PhD candidate in Politics in the Department of Political Economy at King’s College London. His works on comparative politics in the European Union and researches political parties, campaigns and electoral behaviour. He tweets @turnbulldugarte.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.