‘Votes for life’ for overseas electors? Principles, process and party politics

A Private Member’s Bill to extend the franchise to all British citizens living abroad is currently under consideration in Parliament. Susan Collard explains how these proposed reforms, which have significant implications for democratic participation, have become caught up in parliamentary procedure and partisan disputes.

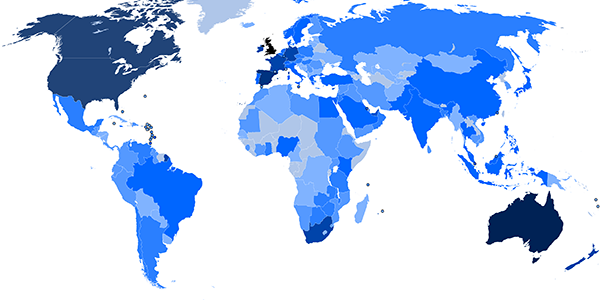

A map of the world by number of residents with British citizenship in 2006. From the BBC report titled ‘Brits Abroad’. Picture: TastyCakes on English Wikipedia, via a CC BY-SA 3.0 licence/Wikimedia Commons

The turmoil around Brexit dominating British politics over recent weeks has turned the public gaze away from other bills going through Parliament. Yet one of these is a bill with significant implications for British democracy: the Overseas Electors Bill 2017–19, a Private Member’s Bill sponsored by the Conservative MP for Montgomeryshire, Glyn Davies. The Bill aims to introduce ‘votes for life’ for Britons living abroad by abolishing the current ‘15 year rule’ which means UK citizens lose their vote 15 years after leaving the country. Since an estimated 3.5m British citizens could be affected, this Bill would represent a major extension of the franchise. It also marks an important departure from a system where residence rather than citizenship has been the traditional basis for voting rights. This Bill deserves attention, not only because it raises important questions of principle over defining the demos, but also because it illustrates the obscure parliamentary procedures that govern Private Members’ Bills, and in doing so, goes to the heart of party politics.

Principles and practice: extending the franchise to all non-resident citizens

The UK is unusual in that voting rights are not enshrined in a constitution but in electoral law, and the complex legacy of Empire has engendered a ‘thin’ concept of citizenship. Legislation in 1985 introduced a time-limited franchise (initially five years) for non-resident citizens, many of whom who had campaigned for this following British membership of the EEC. It was hotly contested by those who believed it contravened the sacrosanct principle of geographical connection to a constituency, traditionally the bedrock of the British parliamentary system. But over time and after several changes in the legislation, the idea of unrestricted expatriate voting has gradually become more acceptable as technology has transformed global communications, allowing people to follow domestic affairs in real time. By removing the cut-off point, this Bill would align the UK with most other European states, and fulfil expatriate demands for recognition of citizenship not residence as the basis for their voting rights.

Supporters of the Bill make four main arguments:

- It would bring ‘electoral justice’ to all UK citizens living abroad who are currently the object of discrimination because of their place of residence.

- It recognises the time limit on voting rights as arbitrary, introduced in another era when living abroad could be assumed to lead to a loss of connection with the UK.

- It is part of a wider ambition to strengthen British democracy.

- It would recognise the importance of the ‘soft power’ of British citizens around the world in contributing to the UK’s interests, especially important in a post-Brexit era.

The politics of overseas voting

The Bill has been presented as ‘non-political’, but this is problematic since ‘votes for life’ was included in Conservative Party manifestos in 2015 and 2017, and because historically the issue of overseas voting has been politically controversial. In previous parliamentary debates, Labour hotly contested the enfranchising of Britons abroad, not only because it challenged the established principles of a constituency-based democracy, but because it was seen as ‘international gerrymandering’. Considered to be disproportionately affluent, expatriates were assumed to be mainly Conservative voters and vivid language was used by Labour MPs to denounce them as ‘people who have put two fingers up to this country’, or as ‘tax dodgers, crooks, thieves and wastrels’.

Twenty years on, the discourse of opposition has changed, but objections remain, albeit less clear-cut: in the debates over this Bill so far, democratic principles and partisan interests have featured much less in Labour’s arguments than concerns for hard-pushed and under-resourced electoral administrators who will carry the burden of implementing the Bill, as highlighted by the Electoral Commission and the Association of Electoral Administrators (AEA). This new official line of opposition was justified by Shadow Minister for the Constitution, Cat Smith, in the Second Reading debate in February, and confirmed in a letter to veteran expat campaigner Harry Shindler in June. During the four sittings of the Committee Stage in October and November, it was fleshed out in a long list of proposed technical amendments and new clauses, though none were successful.

The politics of parliamentary process

But Labour’s opposition to this Bill is also motivated by objections relating to parliamentary process. Shortly before the Bill’s Second Reading in February it became clear that the government was backing Glyn Davies’s Bill as a ‘Handout Bill’. The use of a Private Member’s Bill to introduce a party manifesto pledge was criticised as an abuse of executive power, undermining backbenchers’ limited opportunities to present legislation. Yet this practice is not uncommon, and few such bills become law without government or cross-party support. However, since the Overseas Electors Bill redefines the franchise, Labour also argued that a Public Bill would have been more appropriate, enabling a wider discussion including votes at 16, supported by several opposition parties. It responded to the use of the Handout Bill by trying (unsuccessfully) to ‘talk it out’ (otherwise known as ‘filibustering’), a classic tactic from the arcane set of rules and procedures governing Private Members’ Bills that has been much criticised by the House of Commons’ Procedure Committee.

Labour renewed its procedural attack on the Bill during its Money Resolution debate in October, by adopting another tactical device not used since 1912, to table an amendment that would, if successful, have prevented its implementation by limiting the necessary expenditure. This was in retaliation to the government’s refusal of a Money Resolution for the ‘Parliamentary Constituencies Bill’ sponsored by the Labour MP Afzal Khan, which aims to maintain the number of constituencies at 650, contravening the government’s planned reduction to 600.

During the committee stage that followed, Labour appeared again to be trying to talk out the Overseas Electors Bill with more proposed amendments, until proceedings came to an abrupt conclusion in the Fourth Sitting: it would seem the whips had come to an agreement to defer the debate.

Principles, process or politics?

The real motives behind Labour’s opposition to this Bill are unclear but are probably a complex mix of principles, process and politics, reflecting different views within the party: the language of adversity is less explicit than in the past, but partisan undercurrents are still palpable and there is no evidence that the current leader has accepted that his earlier categorisation of Britons living abroad as disloyal tax exiles is now outdated.

Debate will resume at the Report Stage on 25 January 2019, notwithstanding possible disruptions to the parliamentary timetable. New amendments will be tabled, and the Bill could still be talked out. If it should progress to the House of Lords, it will lose the security of the government’s (fragile) majority.

Many technical aspects of the Bill still deserve further discussion, such as the legal definition of residence and its impact on place of registration, the regulation of the permissibility of party donors abroad and the impact of significantly increased numbers of overseas electors on constituencies highlighted by the Liberal Democrats; although the principle underpinning this Bill is simple, its implementation will be complex.

All previous debates on overseas voting concluded with a compromise between the parties, but since the main issue is no longer the length of a time restriction, it is not clear how a ‘Goldilocks solution somewhere in the middle’ might emerge this time. If it should, proceedings so far suggest it will come not from the floor of either House but from negotiations in the backrooms. The interpretation of opposition to votes for life as ‘grounded in [petty] party politics’, has been criticised as doing ‘grave disservice to broader and pressing issues about who the UK’s democracy should work for’. However, the debates on this Bill so far surely confirm that issues around the franchise are indeed fundamentally framed by party politics. To acknowledge this is not to deny the importance of the wider issues, but to ignore it suggests a failure to read between the lines and behind the scenes of parliamentary discourse.

Readers who would like to know more about the progress of this Bill and about overseas voting more generally can visit a new website: www.britonsvotingabroad.co.uk

This post represents the views of the author and not those of Democratic Audit.

About the author

Susan Collard is a Senior Lecturer in Politics at the University of Sussex. Her teaching expertise is in French and European politics and her current research interests revolve around issues relating to transnationalism and the politics of voting across borders.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

The piece is a very balanced analysis. It makes a small procedural error – the distinction is not between Private Member’s Bill and “Public Bill” but between PMB and “Government Bill”. Both PMBs and Government Bills are “public bills” (that is, change the general law) and these are contrasted with “Private Bills” which only affect the rights and powers of a defined group (usually providing for infrastructure projects or the powers of a local authority or similar body).

Many thanks for this correction, sorry only just seen! Much appreciated. Please get in touch via my university email?