Many interest groups are more in line with public preferences than commonly thought

While some see lobbying as a threat to democracy, others portray interest groups as an important link between the public and the political system. But to what extent do interest groups actually support what the public wants? Linda Flöthe and Anne Rasmussen present a detailed cross-national comparison of congruence between interest groups and the public. They illustrate that despite the negative image of interest groups in politics, their positions are in line with public opinion more than half the time. Moreover, while business interests are often feared the most, a sizable share of them hold preferences in line with a majority of the public.

Picture: © European Union 2018 – European Parliament, via a CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 licence

According to the Corporate Europe Observatory campaign group, as many as 30,000 lobbyists are working at influencing EU politics, a number that roughly corresponds to the staff employed by the European Commission. By some estimates, “these shadowy agitators are estimated to influence 75 per cent of European legislation”. This negative view of interest advocacy is not unique to the EU: more than half of those asked in Germany and the UK in Transparency International’s 2013 Global Corruption Barometer responded that their national governments are run by self-interested groups rather than for the benefit of the general public. Lobbying is often viewed negatively and is likely to account, at least partly, for an increasing scepticism towards the political elite.

Whether the interest group system is biased has also been on the academic agenda for decades and is perhaps the most central question in the study of interest groups. However, the literature lacks a common benchmark for judging the representativeness of organised interests. Many studies have drawn inferences about bias from simple frequencies of the activity and presence of different group types. The dominance of business groups has been seen as particularly problematic since such interests can be expected to represent more narrow, special interests rather than the diffuse interests of the population as whole. Yet to date we have little systematic evidence showing how valid such expectations are in practice.

In a recent study, we propose a new benchmark for assessing bias. We conduct the first cross-national study of congruence between the public and interest groups examining how closely the positions of interest groups and the public are aligned on a diverse set of 50 policy issues in five countries. Issues in our sample concern for example the question of whether to ban smoking in restaurants or to cut social benefits. On each issue we compare support for specific policy changes in opinion polls with group attitudes towards the changes. We coded the latter with the help of newspaper articles, official documents, interviews with civil servants and a survey of the interest groups. We identify a number of different ways of conceptualising and measuring congruence between public opinion and interest group positions.

Our findings show that even if the role of interest groups is typically not to represent the public as a whole, 54% of the advocates actually hold a position that is congruent with the public majority. Looking at congruence between different group types and the public we find some expected differences. Public interest groups, such as NGOs, environmental groups and consumer groups, are for example most likely to be aligned with the public majority than the other group types: 78% of them defend the position of the public majority. This is to be expected since these groups represent wider societal interests and may also be more likely to take note of public opinion, while groups representing a narrow interest focus on securing benefits for a more exclusive set of members.

However, our findings also provide some nuance to several of the conventional wisdoms with respect to interest group type and bias. Most importantly, we show that the types of groups subject to criticism are not always as unrepresentative of public opinion as one might expect. Hence, we see that even if the scores for business groups and firms are lower than the ones for public interest groups presented above (41% and 45% respectively), a sizeable share of business interests are also aligned with the public majority. The same applies to other types of interest groups which represent narrower economic interests: 60% of trade unions and occupational groups are also aligned with the majority of the public.

Table 1: Actor level congruence between interest groups and the majority of public opinion

Note: For more information, see the authors’ accompanying article in the Journal of European Public Policy

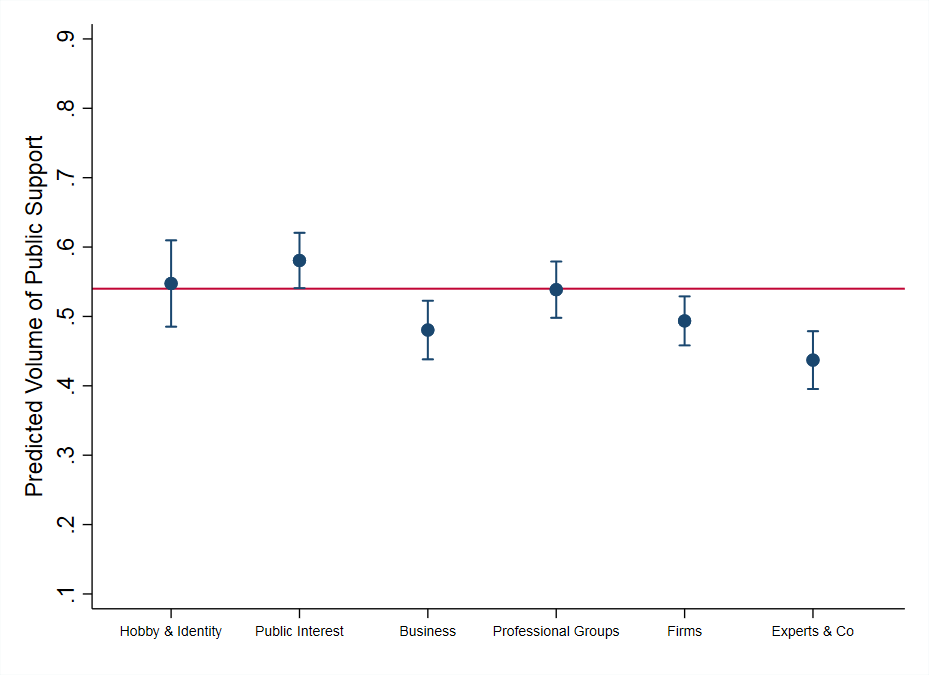

This pattern is even more pronounced when we look at the actual share of the public that share the view of a given interest group rather than just whether the group is supported by a majority of the public. According to Figure 1, public interest groups again score highest, with the largest share of the public on their side. Yet several of the group types representing more narrow interests, such as trade unions and identity groups, do not enjoy significantly weaker public support than public interest groups. Even business groups and firms promote views that almost a majority of citizens share. Hence, whereas we see some expected differences in the extent to which different types of groups are aligned with public opinion, the differences are not always substantial.

Figure 1: Predicted volume of public support for different actor types

Note: For more information, see the authors’ accompanying journal article. Plot based on Model 2. The red line marks the lower confidence interval for public interest groups, showing that public support is only significantly different for business groups, firms and expert organisations.

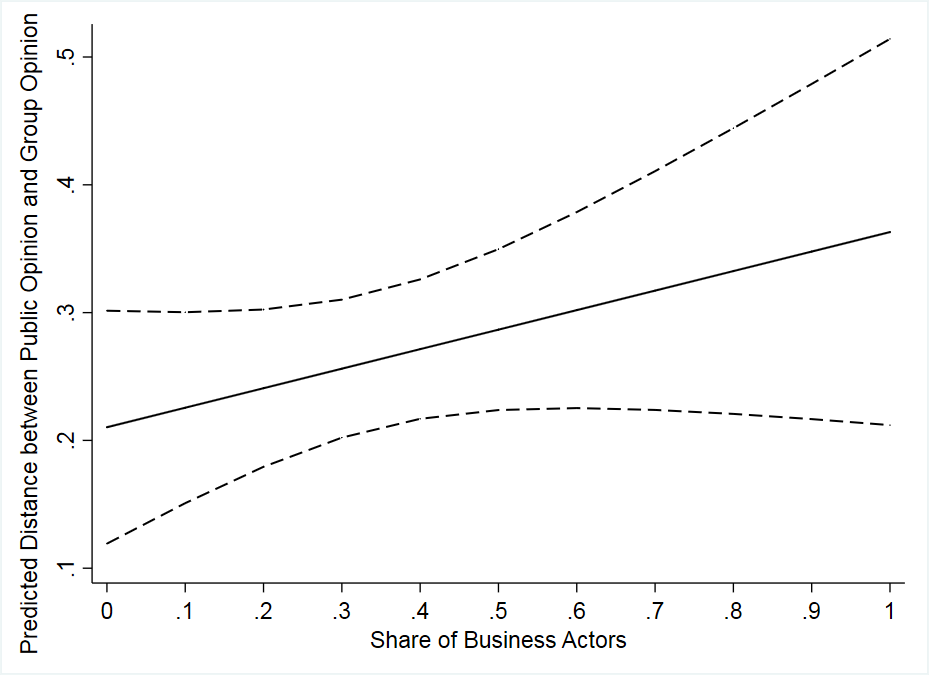

We also studied whether the public is represented better on issues where only one, or a diverse set of interest groups mobilise. One of the indicators used was how dominant business actors were among the active groups on an issue. While Figure 2 shows that a higher share of active business advocates increases the distance between the public and the advocates, we see that the effect is not statistically significant.

Figure 2: Share of business actors and predicted distance between public opinion and group opinion

Note: For more information, see the authors’ journal article. Plot based on Model 6.

Our findings neither confirm nor disconfirm the fears of advocates being ‘shadowy’ actors. They underline that, rather than seeing groups as representatives of minority interests only, many interest groups take at least positions that a majority of the public agrees with. Having over a little more than half of the groups aligned with the public majority is of course ultimately no guarantee that all groups will act as a transmission belt between the public and decision-makers. Political systems should not approach groups in an uncritical manner. But our study paints much less of a grim picture of groups and lobbying than the one typically found in empirical commentary and parts of the academic literature.

Moreover, while there are many ways of categorising groups and calculating bias in the group community in practice, our study raises a note of caution against drawing simplistic conclusions about representativeness based on group type alone. While firms and business groups enjoy weaker support for their positions among citizens than public interest groups, the pattern is less clear for other group types representing narrower interests. The fact that some types of interest group represent narrower public constituencies does not disqualify them from acting in line with public preferences altogether. On the other hand, some public interest groups supposed to represent wider societal interests may be more distant from their grassroots and the public than is sometimes expected.

For more information, see the authors’ accompanying article in the Journal of European Public Policy.

This article gives the views of the authors, and not the position of Democratic Audit. It was first published on the LSE’s European Politics and Policy blog.

About the authors

Linda Flöthe is a PhD candidate at the Institute of Public Administration at Leiden University.

Linda Flöthe is a PhD candidate at the Institute of Public Administration at Leiden University.

Anne Rasmussen is Professor at the Department of Political Science, University of Copenhagen and Professor II at the Department of Comparative Politics, University of Bergen. She is also affiliated to the Institute of Public Administration at Leiden University.

Anne Rasmussen is Professor at the Department of Political Science, University of Copenhagen and Professor II at the Department of Comparative Politics, University of Bergen. She is also affiliated to the Institute of Public Administration at Leiden University.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.