The realignment of European voters and parties over cultural values is transforming political competition

Over the past 40 years, both citizen and party elite opinions on economic and cultural issues have shifted, with increasing cultural cleavages gaining particular significance. Russell J Dalton demonstrates how these changes are transforming current European party competition and electoral dynamics.

Picture: European Parliament, via a CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 licence

In the classic American movie, Back to the Future, the main characters time travel back three decades to change their future. In a new book, Political Realignment, I travelled back to the 1970s (via data analyses) to track how the politics of the 1970s led to the political future we are witnessing today. The past evolutionary realignment of European party systems – for both voters and parties – suggests the future course for electoral politics.

Back to 1979

The first European Parliament direct elections in 1979 occurred as the member states were confronting some of the social changes arising from neo-liberal economic policies and globalisation. In addition, new cultural issues on environmentalism and social equality were entering the political agenda.

I used a statistical method (PCA) with a survey of Candidates for the European Parliament (CEPs) to measure party elite positions along an economic issue dimension and a cultural issue dimension. Economic issues dealt with the role of government and the representation of class interests. Cultural issues included abortion rights, nuclear power, terrorism and military defence.

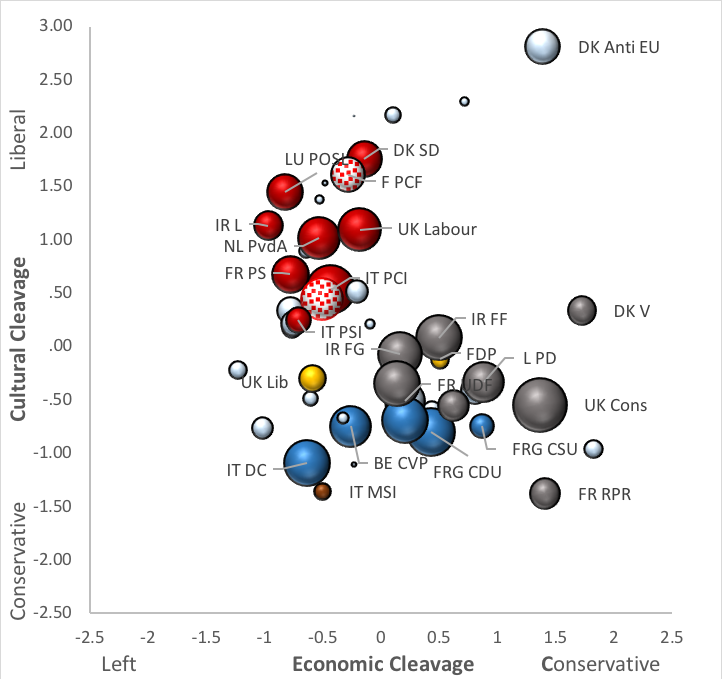

Figure 1 maps party positions in the EU9 member states in 1979. The traditional Left-Right economic cleavage is clearly apparent. The conservative parties (in black), such as the British Conservatives and French RPR, are to the right on the economic cleavage, while the Labour and Social Democratic parties (in red) are to the left of centre, although only slightly so.

Figure 1: Parties in the cleavage space, 1979

Source: Candidates for the European Parliament survey, 1979.

Note: Figure entries are party elites’ mean scores; each bubble reflects the party’s 1979 vote share.

On the cultural cleavage, elites in Labour/Social Democratic parties already lean toward liberal cultural positions. This probably arose as an appeal for liberal middle-class voters, but also reflects elites’ own affluent, highly educated and middle-class views. Indeed, elites in most large leftist parties are more liberal on cultural issues than many of their own supporters. In contrast, religious parties (in blue), such as the Italian Christian Democrats and the German CDU, are the clearest representatives of cultural conservatism.

A parallel survey of European citizens shows that social groups in this two-dimensional space reflect traditional group alignments. The economic dimension is anchored by social class: professionals, executives and business owners are economic conservatives, while the working class leans toward the left. In contrast, most social groups, with the exception of the religious/secular divide, only modestly differ on the cultural cleavage. These patterns are my baseline for studying electoral change.

Next stop, 1994

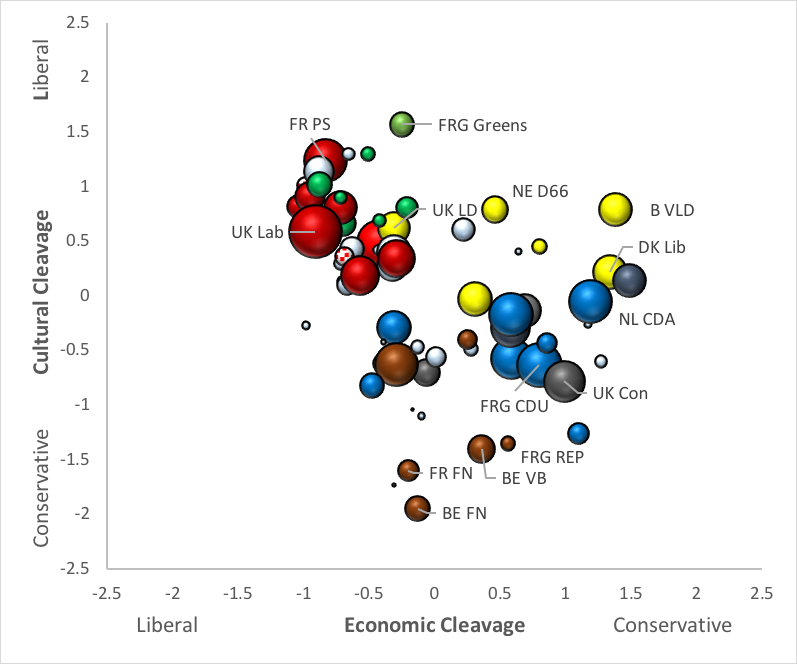

By 1994, the forces of social modernisation were reshaping European party systems (Figure 2). New Green parties are vocal advocates of progressive cultural values. However, the progressive drift of Labour/Social Democratic elites overlaps with Green parties. Indeed, Labour/SD elites are generally more culturally liberal than economically liberal. Many Conservative and Christian Democratic parties had moderated their cultural positions on issues, such as divorce and women’s rights reforms, to appeal to some liberalising middle-class voters.

This shift by the traditional Left and Right parties toward cultural liberalism created a political void, and even by 1994 new parties were representing this constituency. The French National Front, the Belgian National Front, and similar parties gave voters a clear culturally conservative choice. As new political contenders, the extreme positions and their populist style of far-right parties probably helped them to mobilise new support.

At the same time, the established parties seem to locate the same relative positions on the economic cleavage as 15 years earlier. The Left is represented primarily by Labour/SD parties, as communist parties declined after the fall of the Soviet Union. Liberal and conservative parties persisted in their economic conservatism. Elites in far-right parties generally held centrist economic positions to attract voters of all economic views.

Figure 2: Parties in the cleavage space, 1994

Source: Candidates for the European Parliament survey, 1994 (EU9).

Note: Figure entries are party elites’ mean scores; each bubble reflects the party’s 1994 vote share.

2009 and beyond

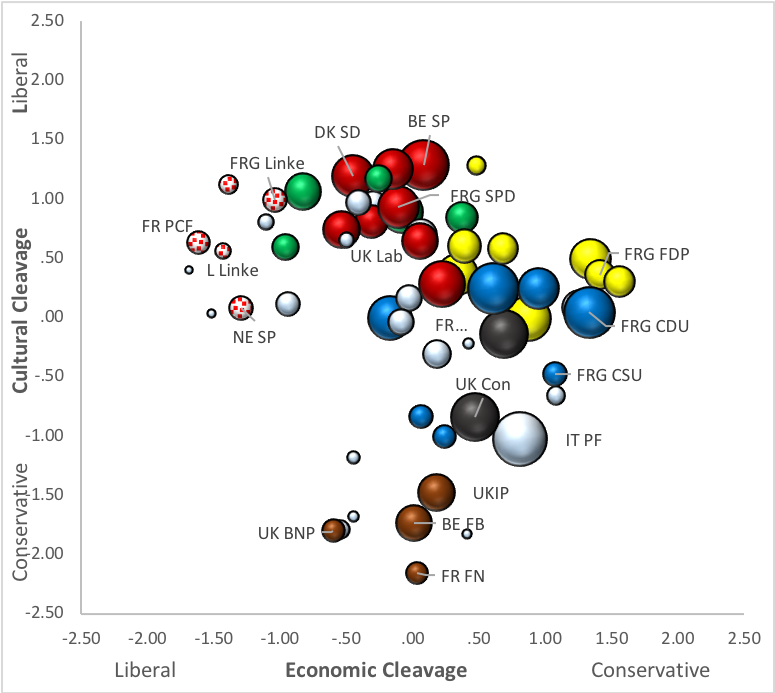

Our time machine then moves us forward another 15 years to 2009 and a new CEP survey. The number of parties and their political diversity has expanded. If anything, the economic cleavage is more distinct – perhaps because of the 2008 financial crisis. Now liberal parties (yellow) and traditional conservative parties are counterbalanced by reformed/post-communist parties on the extreme left (speckled red). Most Labour/Social Democratic parties are positioned near the centre of the economic cleavage not far from traditional conservative parties.

Figure 3: Parties in the cleavage space, 2009

Source: Candidates for the European Parliament survey, 2009 (EU9).

Note: Figure entries are party elites’ mean scores; each bubble reflects the party’s 2009 vote share.

The cultural cleavage also distinctly structures party choices. Green parties define the liberal cultural pole, intermixed with Labour/SD parties. Many established conservative and Christian Democratic parties also moderated their views on cultural issues. These developments expanded a political void in the party space, which opened the potential for far-right cultural parties (brown). This has become even more apparent in subsequent elections.

Social groups also realigned their positions in this political space between 1979 and the 2009 European Election Study. Class differences on the traditional economic issues narrowed over time. A recent study of British trends finds a similar class realignment from the 1960s to the present.

An even starker realignment involves social groups on the cultural cleavage. Professionals, executives and managers are now the vanguard of cultural liberalism, while business owners and the working class adopted conservative cultural positions. Equally striking, small educational differences on the cultural cleavage evolved into a very large education gap by 2009. Moreover, the highly educated and professional occupations have grown in size, while the less educated and the working class decreased. Age groups also polarised along the cultural cleavage with younger Europeans gravitating toward liberal cultural views. Thus, the traditional class and socio-economic alignments that once structured European party systems no longer exist.

Back to the Future II

Electoral politics is an interaction between citizens’ political demands and the supply of political choices offered by the parties. Two main forces generated party realignments across Europe. First, as political power shifted from labour to capital and from the working class to the well-educated and professional middle class, Labour/Social Democratic parties realigned their positions towards the economic centre and liberal cultural policies. This distanced these parties from their traditional working-class base. Established conservative parties shifted towards even more conservative economic policies and moderated their cultural positions.

Second, new Green parties strengthened a progressive cultural agenda. Eventually, far-right parties formed to oppose this progressive agenda and articulate an alternative programme. My book argues that far-right parties and their voters reflect a backlash to the forces of modernisation that have transformed Europe since the postwar era.

What came first, did political elites realign their positions and thereby redefine the lines of political competition – or were voter blocs already shifting their political values and the (old and new) parties supplied them with representation? Both options are probably true to a degree, but I lean more toward the latter explanation.

The economic and cultural dimensions comprise important policy concerns, engrained in social groups, and now represented by distinct party choices. My time travels showed that the cultural cleavage has become more central than economics in structuring citizens’ political thinking, electoral choices, and party representation linkage. I expect contemporary party systems will continue responding to both political forces.

The current party space thus offers dramatically more political choice for voters. A diverse party system might increase the representation of citizen policy views, but it also creates challenges for political parties. Election strategies become more complex and less predictable in a multidimensional competition. The volatility of electoral results and increased fluidity of voter choice are likely to continue. More parties in parliaments make coalition formation and governing more difficult. This is the new political reality for parties and governments.

Finally, a puzzle remains. If social modernisation promotes progressive values, why is there heightened opposition on cultural issues today? Data from the American National Election Studies, for example, show a growth in modernising values since the 1980s, at the same time as these values become more polarising in vote choice. Even before the 2008 recession and the 2015 refugee crisis, far-right parties and hard-left populism tapped into a backlash to rapid political change that left some parts of society underrepresented. If politicians exploit these tensions for personal or partisan advantage, as some are doing today, this will harm the democratic process. But if these disruptions prompt necessary political reform and a wider representation of citizen opinions, democracies and their citizens will benefit.

This article represents the views of the author, and not those of Democratic Audit. It draws on his book, Political Realignment: Economics, Culture, and Electoral Change (Oxford University Press: 2018).

About the author

Russell J Dalton is Professor of Political Science at the University of California, Irvine.

Russell J Dalton is Professor of Political Science at the University of California, Irvine.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Interesting piece but I fail to grasp the conclusion. This is what it says: “If politicians exploit these tensions for personal or partisan advantage, as some are doing today, this will harm the democratic process. But if these disruptions prompt necessary political reform and a wider representation of citizen opinions, democracies and their citizens will benefit.”

What does that mean? All political parties “exploit” issues for partisan advantage – you have only to look at the Democrats over confirmation of Kavanaugh. Or the various groups in the UK making clear that they will vote down the potential Brexit plan, on openly stated partisan grounds.

And “for personal reasons”? What is that in politics if not an expression of your personal beliefs? Or are we talking cash and cars and yachts?

If the author is saying that those challenging (like the Socialists say 100 years ago) must keep quiet and try not to campaign or be visible, then the horse has bolted; the old elite has repeatedly smeared and lied about challengers to such a degree that the new diverse politics will not put up with the crony capitalism and the tired political class with its seats reserved on the google jet. If you want power you have to be as firm about it as the old elite clinging on. It is surely they who are damaging and besmirching democracy with endless lies and misrepresentations and fearmongering to the electorate over new and diverse forces. Using the media and tame journalists to smear and plant fake news.

One person’s “exploit the tensions” is another person’s campaigning and route to power. If we do not approve of someone’s views, this does not mean that they are doing it all for some nefarious reason and that their possible success witll “damage democracy”. That has been damaged by the old elite already – and anyway, this is what almost all middle class commentators said 100 years about the left and socialism – ‘rabblerousers…envy…populists…evil”. The list of their splenbetic energy on the subject could fill a book (and did).