Does democratic discontent foster support for challenger parties?

Established parties across Europe are being challenged by the growth in new parties on the left and right. To assess the extent to which support for challenger parties is a result of dissatisfaction with existing democratic practices, Enrique Hernández has developed a model to distinguish different forms of democratic discontent. He finds that the specific focus of a voter’s democratic discontent shapes their support for these parties, and that this varies between left- and right-wing challenger parties.

Podemos supporters, 2015. Picture: Bloco via a (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0) licence

Podemos supporters, 2015. Picture: Bloco via a (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0) licence

European democracies have witnessed an upsurge of challenger parties of different stripes during the last decade. Parties such as the M5S in Italy, Podemos in Spain or the Front National in France have gained considerable electoral support. During this period Europeans have also become less satisfied with the way their democratic institutions work. In a recently published article, I argue that while discontent with the functioning of democracy can be generally linked to a higher propensity to vote for challenger parties, the relationship between democratic discontent and party choice is more complex and nuanced than it seems.

To understand the link between democratic discontent and party choice one must first acknowledge that there are different aspects of democracy with which citizens might be dissatisfied. For example, a person could think that her democracy works well with regards to the fairness of elections but not when it comes to the protection of the rights of minorities. Second, we also need to distinguish between different types of challenger parties. Depending on their ideological leaning, these parties differ in the kind of problems of democracy that they emphasise, as well as in the solutions they propose to solve them. Therefore, left- and right-wing challenger parties should mobilise voters with different forms of democratic discontent.

To test this expectation I use data from fifteen Western European countries from the sixth round of the European Social Survey (fielded in 2012 and 2013). This survey includes a unique battery of questions in which respondents first give their opinion about the importance of different democratic principles in an ideal democratic system, and are then asked to what extent they believe that each of these principles are applied in their respective country.

To distinguish between different forms of democratic discontent, I consider not only two principles related to liberal models of democracy (namely, the freedom and fairness of elections and the protection of minorities’ rights), but also three principles that go beyond procedural and minimalist models of democracy. These principles are: (i) the citizens’ involvement in decision making through referenda (direct-democratic model of democracy); (ii) the reduction of economic inequalities (social-democratic model of democracy); and (iii) the need for national governments to take into account the opinion of other European governments before adopting decisions (responsible model of democracy). For each of these principles I estimate if individuals perceive that, with respect to their ideal model of democracy, their political system is underperforming (democratic deficit), it is overperforming (democratic surplus), or it is working just about right.

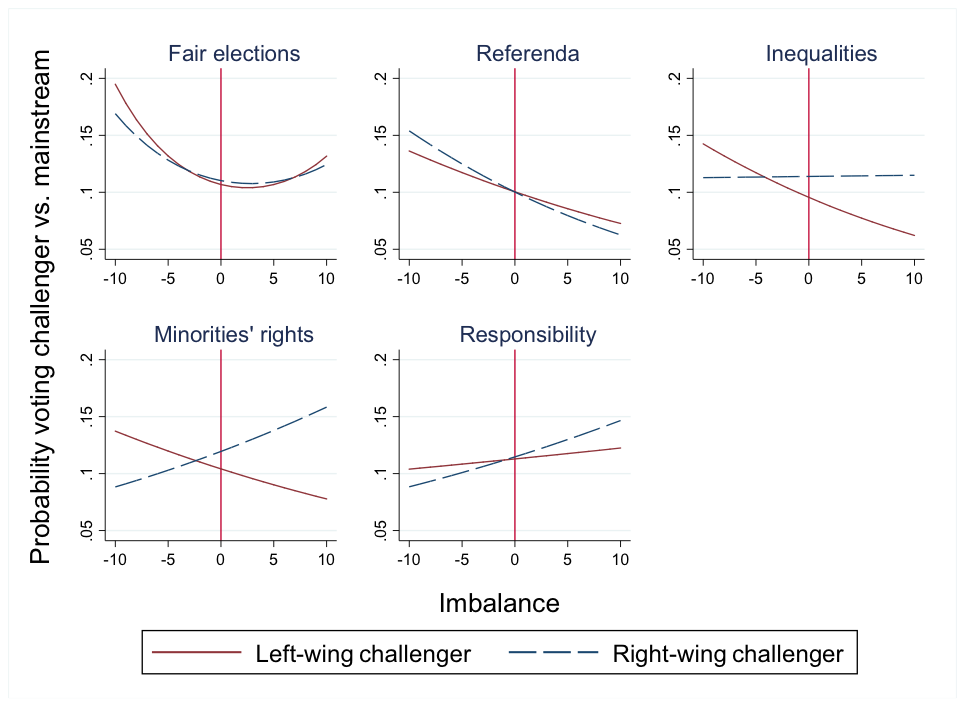

Figure 1 summarises the probability of supporting left- and right-wing challenger parties depending on whether citizens perceive a democratic deficit or surplus for each of these five principles of democracy. In each of the panes negative values located to the left of the red line denote a democratic deficit and positive values located to the right denote a democratic surplus. Take the principle of the protection of minorities’ rights as an example. A score of 0 in the imbalance measure indicates that the respondent believes that the protection granted to minorities in her country matches her ideal model of democracy. Negative values indicate that she believes that compared to her ideal model of democracy the rights of these groups are not sufficiently protected (democratic deficit), and positive values indicate that she believes that the rights of minority groups are excessively protected (democratic surplus).

Figure 1: Probability of voting for left- and right-wing challenger parties among those perceiving democratic deficits and surpluses for five principles of democracy

Source: Based on Model 7 from ‘Democratic discontent and support for mainstream and challenger parties: Democratic protest voting’

The results in Figure 1 show that those perceiving that elections are not fair enough or that citizens should be allowed to vote more often in referenda are more likely to support left- and right-wing challenger parties alike. In these cases, the two types of challenger parties mobilise those perceiving a democratic deficit. However, when it comes to the other three principles of democracy we observe clear differences between left- and right-wing challengers. As citizens perceive a greater democratic deficit related to the reduction of economic inequalities they become more likely to cast a vote for a left-wing challenger, but not for a right-wing challenger. These differences between challenger parties are even more apparent for the principle of protecting minorities’ rights. In this case, perceiving that the rights of minorities are less protected than they should (deficit) is associated to a higher likelihood of supporting a left-wing challenger. Conversely, perceiving that the rights of these groups are more protected that they should (surplus) increases the likelihood of casting a vote for a right-wing challenger. Finally, for the responsibility principle only right-wing challengers appear to significantly mobilise those who think that their national governments take too much into account the views of other European governments before adopting decisions (democratic surplus).

The implication of these results is that discontented citizens will not vote for any challenger party, but for a party that is aligned with the specific shortcomings that they perceive in their democracy. Therefore, the process by which democratic discontent relates to party choices is not only influenced by citizens’ desire to protest, but also by what citizens want to protest about. While challenger parties can be considered an electoral alternative for those who want to cast a protest vote and express their democratic discontent at the polls, not all challenger parties mobilise the same types of democratic discontent.

This post represents the views of the author and not those of Democratic Audit. It draws on his article ‘Democratic discontent and support for mainstream and challenger parties: Democratic protest voting’, published in European Union Politics.

About the author

Enrique Hernández is a post-doctoral fellow at the Democracy, Elections and Citizenship research group at the Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona. Enrique’s main research interests are in political attitudes, public opinion, electoral behaviour, and political participation.

Enrique Hernández is a post-doctoral fellow at the Democracy, Elections and Citizenship research group at the Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona. Enrique’s main research interests are in political attitudes, public opinion, electoral behaviour, and political participation.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.