England’s local elections 2018: why the results will matter for both government and opposition parties

On Thursday, 3 May, there are local elections in many towns and cities across England, including London. Tony Travers assesses what is at stake for the main parties, and what the key benchmarks for success will be in terms of local results and national equivalent vote share.

Picture: STML, via a (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0) licence

Local elections in many countries are used as a ‘real world’ test of public opinion in the years between national elections. This reality can often disguise the importance of local choice in determining the quality of local services. Municipalities can perform well or badly and the ballot box encourages competition between parties in the provision of schools, social care, environmental services, roads and housing.

The 2018 council elections in England take place eight years into an unprecedented period of ‘austerity’. In the period since the Conservative-Liberal Democrat coalition took office in 2010, local authority expenditure has been cut by a quarter in real terms. For some places, mostly in cities, this cut has been closer to 40 per cent. Of course, no council leadership can campaign by saying anything other than ‘we have delivered good services for a reasonable local tax’. The government has been politically astute by protecting its own expenditure such as the NHS and pensions, while taking an axe to local authority provision.

Austerity is a real local issue, as is the perceived quality of each council’s services. National politics, in the shape of the recent row over anti-semitism affecting the Labour Party and the Conservatives’ role in the ‘hostile environment’ migration policy affecting the Windrush generation of Caribbean immigrants (culminating in Home Secretary Amber Rudd’s resignation), has dominated the media in recent weeks. Such nationally politically salient issues will undoubtedly influence some people’s votes on 3 May.

This year’s elections take place in England only, mostly in cities. Theses seats were last fought in 2014, except where have been major boundary changes. The 32 London boroughs have all-out contests, with a mixture of all-out and one-third elections in 34 out of 36 metropolitan districts. The all-out contests in Manchester, Birmingham, Leeds and Newcastle take place because of re-warding there. Hull, a unitary authority, will also see all-out elections because of ward boundary changes, with one-third polls in 16 other unitary authorities. In 68 non-metropolitan districts, there are a mixture of elections which variously involve all, a half or a third of the sitting councillors.

Four of the London boroughs (Hackney, Lewisham, Newham and Tower Hamlets) are holding mayoral elections, as is Watford. In South Yorkshire, the area will hold its first-ever vote for a city-regional mayor.

Although this year’s elections are predominantly in urban areas, psephologists will use the results to calculate ‘national equivalent vote shares’ (NEVS) to estimate what a fully representative national vote would have been on the basis of the places which actually vote. Such vote-share calculations are very important for the national parties as a benchmark of their strength in-between general elections.

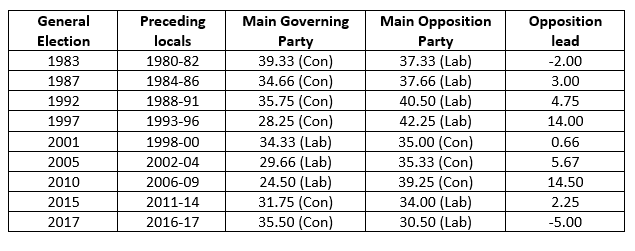

The table below considers both the government and opposition performance in local elections in the years between general elections throughout the period from 1979 to 2017. The simple average NEVS for the main government and opposition parties is shown for each inter-election period. The difference between the two sets of NEVS figures is shown in the last-but-one column.

National equivalent vote share (NEV) for years between general elections

Source: House of Commons Library Local elections 2017 (based on publications by Colin Rallings and Michael Thrasher), plus author’s calculations

This table suggests it has been necessary for the main opposition party to lead the government party by a substantial margin, on average, between elections if it was to have a serious chance of winning the next general election (ie in 1997 and 2010). Labour’s performance in this year’s local elections will give us a powerful clue how well it may do in a 2021 or 2022 general election.

Labour is expected to do reasonably well in London this year, particularly after the party’s success in the capital in the 2017 general election, when it won 54.5 per cent of the vote. Labour controlled 20 boroughs after the 2014 elections, with the Conservatives having nine and the Liberal Democrats one. Two were ‘no overall control’. The City of London, with a rather different franchise, has elections on a different cycle.

Barnet, Hillingdon and Kingston look marginal for the Conservatives, the first two to Labour and Kingston to the Liberal Democrats. Wandsworth would require a larger swing, while in Westminster the Tories have a number of very safe wards which would be hard for Labour to win without a swing of perhaps 10 per cent. Bexley, Bromley, Richmond and Kensington & Chelsea look safe for the Conservatives, though the political fallout from last June’s Grenfell Tower fire means the politics of K&C is currently subject to unique pressures.

The Conservatives control only two metropolitan districts: Solihull and Trafford. The former is safe, though latter could produce a Labour win. Labour is two seats short of a majority in Kirklees and three short in Calderdale, both in West Yorkshire. Amber Valley, Swindon and Tamworth are narrowly held by the Conservatives and will be a useful test of how the party is doing outside the capital. Indeed, last year’s general election and recent opinion polls suggest that the Tories may win seats in parts of the Midlands and the North, sometimes in places where the party has struggles in recent years.

EU nationals can vote in local elections, but not in UK Parliamentary polls or referendums. In some London boroughs, 10 to 15 per cent of the electorate are likely to be EU citizens. This factor, along with a residual ‘Remain’ overlay, may help the Labour Party and the Liberal Democrats in a number of London and city authorities. Of course, in areas with a big ‘Leave’ majority in the EU referendum, particularly in the Midlands and the North, the Conservatives may benefit from a ‘Brexit effect’.

This post represents the views of the author and not those of Democratic Audit.

About the author

Tony Travers is a Visiting Professor in the Department of Government at the LSE, Director of LSE London and co-Director of Democratic Audit. He is the author of London’s Boroughs at 50.

Tony Travers is a Visiting Professor in the Department of Government at the LSE, Director of LSE London and co-Director of Democratic Audit. He is the author of London’s Boroughs at 50.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.