How the EU elite publicises its high-profile work and stays silent about the rest

The EU policy process is often criticised for being distant from its citizens. Part of this criticism is rooted in a lack of media coverage of EU legislative decision-making, says Iskander De Bruycker. Drawing on a recent study, he illustrates that the extent to which politicians in Brussels address citizens’ interests in the media over a particular piece of legislation depends on how politicised that issue is. And while EU politicians are more likely to engage with the media on issues that have been politicised by civil society groups, they are less likely to do so over issues that business lobbyists have mobilised around.

In the July plenary at the European Parliament, 2017. Photo: © European Union 2017 – European Parliament via a CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 licence

In the aftermath of the Brexit referendum, the gap between citizens and political elites in Brussels seems wider than ever before. In a recent study, I have examined how EU political elites have sought to overcome this gap by addressing the interests of citizens in media debates. EU political elites include representatives of the European Parliament (MEPs), Council and Member State officials, and civil servants of the European Commission. Claims about citizens’ interests are important signals for elites to show to the public that their voices are being heard. By making claims in the news, EU political elites can thwart or elicit public protest or electoral retribution.

To explain why political elites in Brussels address citizens’ interests in the news, I point to the politicised nature of EU policy processes. Politicisation involves conflict, public scrutiny and intense stakeholder mobilisation. Almost intuitively, we associate politicisation with more democratic quality and control. While indeed, politicisation makes policy processes more visible and citizens more vigilant, it does not always imply that public interests prevail. In many cases, politicisation is elicited by business lobbies and politicisation can bring about policy deadlock. This may harm or delude the public interest. Think about the politicisation of the Financial Transaction Tax or the Eurobonds issue, which eventually led to a policy stalemate.

To study the media claims of EU political elites empirically, I conducted a large-scale content analysis of 2,164 media statements in six European media outlets on a sample of 125 legislative proposals (2008-2010). This data collection was part of the broader INTEREURO project. I found that in 14% of the cases, political elites referred to public interests when making claims about EU public policy, i.e. they addressed the interests of diffuse groups such as ‘taxpayers’, ‘consumers’, ‘patients’ or European citizens in general. For instance, on the legislative proposal regarding roaming on public mobile telephone networks [COM (2008) 580] MEP Viviane Reding said in European Voice: “EU citizens should be free to text across borders without being ripped off… It is not a good sign for the competitiveness of Europe’s mobile industry that it still hasn’t got the message that credible price reductions are needed to avoid regulation.”

Mostly, Members of the European Parliament turn out to be the most vigorous representatives of citizen interests in the media, while European Commission officials and officials of member states and the European Council are less prone to appeal to public interests. EU political elites who support policy initiatives from the European Commission are more likely to address the interests of citizens in the media when compared to elites who oppose the Commission’s policy proposals.

Figure1: Politicisation and public interest appeals in the news for each legislative proposal

Note: For more information, see the author’s accompanying journal article.

The figure above illustrates the number of appeals to public interests in the news and the degree of politicisation per legislative proposal. Politicisation is measured based on an index gauging the number of stakeholders that mobilised, the degree of conflict and the public salience of the issue. Clearly, on some policy proposals appeals to public interests in the news ‘peaked’. For instance, the 2008 regulation proposal regarding roaming on public mobile telephone networks [COM (2008) 580] attracted more than 20 claims addressing citizens’ interests.

Most policy proposals, however, attract hardly any appeals to public interests. Indeed, I find that politicisation affects elites’ tendency to address public interests in the news, which is illustrated by the significantly similar trends of public interest appeals and politicisation in Figure 1. The results thus show that EU political elites are more prone to address public interests in the media under politicised conditions. Yet, the effect of politicisation is contingent on which type of stakeholders (business versus civil society) are involved in policy debates. I illustrate this in figures 2 and 3.

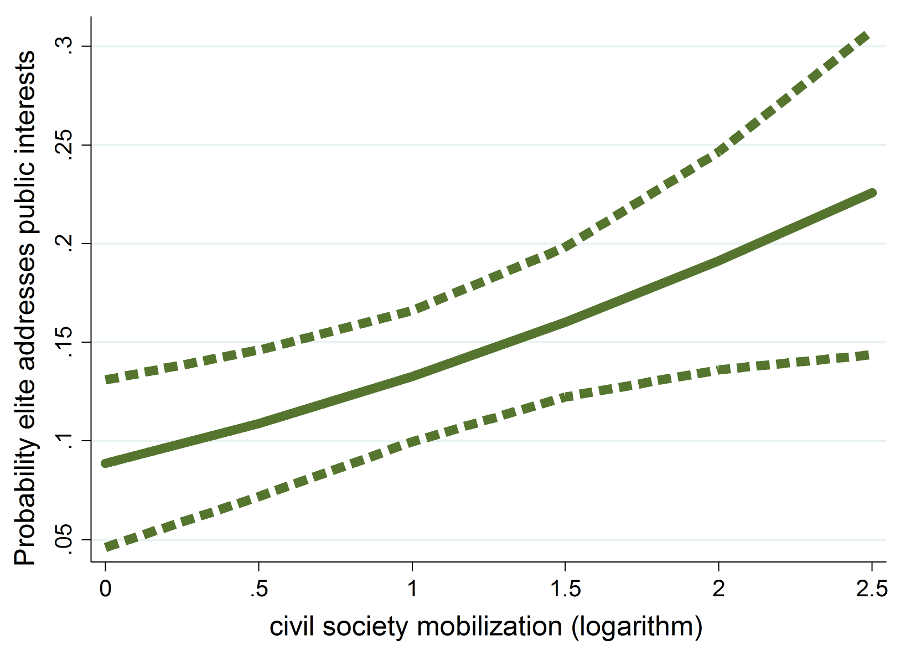

Figure 2: The effect of civil society mobilisation on EU political elites’ tendencies to address public interests in the news

Note: For more information, see the author’s accompanying journal article.

Figure 3: The effect of business mobilisation on EU political elites’ tendencies to address public interests in the news

Note: For more information, see the author’s accompanying journal article.

If civil society groups such as Oxfam, Greenpeace or WWF mobilise (Figure 2), EU political elites are more prone to address public interests in the media. When business lobby groups are active, in contrast, (Figure 3) elites are less inclined to address the interests of citizens in the news. These results hold true after controlling for policy area, public salience and the conflictual nature of policy processes in a regression analysis.

In sum, these findings paint a picture of two different media worlds in EU public policy: one politicised world where civil society intensively mobilises, in which citizens are vigilant and public interests carry the day, and another depoliticised world where elites remain silent about public interests and where business lobbyists thrive. The lion’s share of EU policy processes belong to the latter world – they are not politicised and attract little or no reference to public interest in the news.

For more information, see the author’s accompanying journal article. This post first appeared at LSE EUROPP.

Iskander De Bruycker is a Postdoctoral Research Fellow for the Research Foundation Flanders at the University of Antwerp. He was previously affiliated to the University of Amsterdam and the University of Aarhus. He recently received support from the Research Foundation Flanders for his research project on how public opinion and lobbying influences EU policy decisions.

Iskander De Bruycker is a Postdoctoral Research Fellow for the Research Foundation Flanders at the University of Antwerp. He was previously affiliated to the University of Amsterdam and the University of Aarhus. He recently received support from the Research Foundation Flanders for his research project on how public opinion and lobbying influences EU policy decisions.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

You say at the bottom of the article that the author has received “support” from a body which you do not properly specify as a provider of vast EU funding for propaganda. Is this “support” you refer to a stick to help him stand up, a chair maybe? Two guards to keep him on his feet? A support garment? Or is it a coy euphemism for funds…money which comes from the EU via other shadowy bodies and of course therefore from (among others) British taxpayers. Say so, particularly so if the piece is such slavishly pro-EU propaganda as this.

The ‘Research Foundation Flanders’…which hands out large amounts of EU funds…and which are used to fund EU propaganda (like this).

This is the same as when these sinister money-channel bodies with intentionally bland academic sounding names use EU funding to pay ‘journalists’ (including those on national networks like the BBC, state radio and tv in the UK) enormous sums to “chair’ events or for other nefarious and hidden ‘services’ (paying them large sums ensures that they will self censor and favour the paymaster where the EU really needs it – in terms of concealing inconvenient facts about the EU and bigging up the EU whenever possible in news terms…a bit like this article…).

And let’s look forward to an EU-funded piece (as always, they are not declared to be EU-funded even if it is so at three times removed) which dares to suggest any mild criticism or proper analysis of the Great & Glorious EU…and a proper expose of these sinister and shadowy propaganda bodies – where their money comes from and who it goes to and what the EU is getting by way of paid hireling loyalty from supposed professionals for our cash…we will look in vain and forever. He who pays the piper calls the tune…