The Prevent duty is two years old. What’s really going on in schools and colleges?

The Prevent duty came into force two years ago. Schools and colleges now have to identify students they consider vulnerable to radicalisation and to promote ‘fundamental British values’ in the curriculum. Has this had – as some fear – a chilling effect on free speech? Joel Busher, Tufyal Choudhury and Paul Thomas found staff have tried to pre-empt this by actively encouraging debate. While they are largely confident about implementing Prevent, many are uncomfortable and unsure about promoting ‘British’ values and worried about the danger of stigmatising Muslim students.

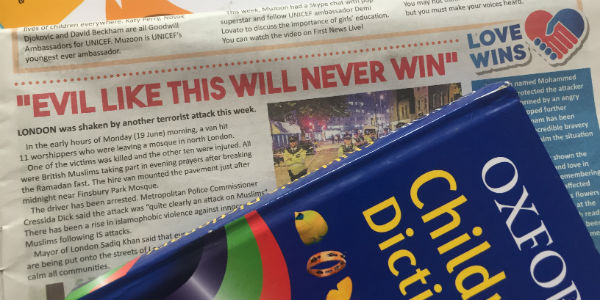

A story from the children’s newspaper First News, June 2017. Photo: Ros Taylor

What happens in schools and colleges when they are placed at the forefront of policy efforts to prevent terrorism and radicalisation? In Britain, a legal duty that came into force two years ago this week – known as the ‘Prevent duty’ – gave us a chance to find out.

The Prevent duty, introduced as part of the Counter-Terrorism and Security Act 2015, requires schools, further education colleges and other ‘specified authorities’ (including universities and health and social services) to show ‘due regard to the need to prevent people from being drawn into terrorism’.

For schools and colleges this entails both a ‘safeguarding’ element – focused on identifying students considered ‘vulnerable’ to radicalisation and reporting them for possible referral to the ‘Channel’ anti-extremism mentoring scheme – as well as a requirement that they build students’ resilience against extremism by promoting ‘fundamental British values’ through their curriculum content and activity.

Ever since the Prevent duty was first announced it has been the subject of often highly polarised public debate. While the government argued that the duty ‘doesn’t and shouldn’t stop schools and colleges from discussing controversial issues’, critics of the duty claimed it would have a ‘chilling effect’ on free speech. Additionally, while the government insisted that Prevent and the Prevent duty relate to all forms of extremism, critics have argued that, whatever the intention of individual policymakers and practitioners, Prevent and the Prevent duty continue in reality to concentrate overwhelmingly on Muslim communities. The duty was therefore likely to exacerbate stigmatisation of Muslim students. These concerns have intensified as a result of high-profile media coverage of controversial Prevent referrals of individual Muslim students. (See, for example, Eroding Trust: The UK’s PREVENT Counter-Extremism Strategy in Health and Education and Preventing Education? Human Rights and UK Counter Terrorism Policy in Schools.)

While acknowledging the need for research into student experiences, our study focused on the experiences of education professionals – including teaching staff, school/college leaders, support and technical staff – in England, drawing on detailed interviews with 70 education professionals in 14 schools and colleges and a national online survey of 225 such professionals. (There are more or less subtle differences in the guidance and implementation in Scotland and Wales. Prevent does not apply to Northern Ireland.)

Three elements of our research are of particular significance.

- We found relatively little support among education professionals for the idea that the duty has led to a ‘chilling effect’ on discussions in the classroom and beyond. In the survey data just over one in ten (12%) respondents stated that the duty had led to ‘less open discussions around topics such as extremism, intolerance and inequality’, compared with 32% who said it had made no difference in this regard, and 41% who said the duty had actually led to more open discussions.

- We believe that part of the explanation for this is that staff who were concerned about this possible side-effect of the duty took pre-emptive action to minimise the risk of such effects emerging e.g. we heard about schools/colleges reinvigorating debating clubs, or promoting more discussion of Prevent-related issues in the classroom.

These findings do not ‘prove’ that there has not been a ‘chilling effect’ – this would require systematic research with students.

- In keeping with earlier research published by the Department for Education, we found fairly high and widespread confidence among school and college staff with regards to the duty. Our data indicate that this is likely to be the product of a number of factors, including effective training, confidence in their professional skills and experience, and trust in their fellow professionals further along the safeguarding referral pathway to accurately identify which cases do or do not require further action.

- What has also been key to this confidence, however, has been the way the Prevent duty has been presented and understood by education professionals as part of ‘safeguarding’. This interpretation of the duty – encouraged by the government and accepted by the overwhelming majority of the education professionals whom we spoke to – has enabled schools, colleges and their staff to incorporate the duty within existing safeguarding policies and processes with which staff were already familiar and comfortable.

- Where we found less certainty and a strong current of criticism, however, was regarding the requirement to promote fundamental British values. We encountered widespread discomfort and uncertainty around the focus on the specifically British nature and content of these values and concern about how this can be translated into inclusive curriculum content and practice.

- While there was broad acceptance of and engagement with the government’s message that Prevent relates to all forms of extremism, we also found widespread – and in some cases very acute – concerns about increased feelings of stigmatisation among Muslim students in the context of the Prevent duty.

Several respondents spoke about how they and their colleagues were seeking to avoid such outcomes – by foregrounding democracy, active citizenship, equality and anti-racism in their activities designed to address the duty; by seeking out materials that foster a balanced understanding of the threats posed by extremism, terrorism and radicalisation; by emphasising to students that Al-Qaeda/IS-inspired terrorism should not be seen to be representative of Islam or Muslims; by introducing students to Prevent training materials that they believed conveyed that the duty was not ‘targeting’ Muslims; or in the case of some school leaders, working with colleagues to try to reduce the number of unnecessary referrals by helping them to feel confident in their own professional judgement.

However, many of the education professionals we spoke with were nonetheless concerned that such efforts might have only limited effect in the context of widespread anti-Muslim sentiment in British society and deep-seated suspicion of Prevent. They were also concerned that, whatever the intentions, in practice the Prevent duty is more likely to focus staff attention on the behaviours and practices of Muslim students because some staff, particularly from non-Muslim backgrounds, may be less sure about how to interpret and assess some of the behaviours and cultural norms of Muslim students.

Our findings paint a more complex and nuanced picture than much of the public debate would have us believe. They indicate that many schools and colleges have deliberately taken steps not just to implement the Prevent duty but to ensure they do so in a way that they believe is likely to minimise possible negative consequences for students and for the school or college environment.

Yet difficult questions remain. How does the link between Prevent and fundamental British values contribute in practice towards reducing the risk of harm to students? What are the possible unintended consequences of the duty for students, and for Muslim students in particular? Systematic research with students and parents would give us a more detailed understanding of their experiences of the Prevent duty.

This post represents the views of the authors and not those of Democratic Audit.

Joel Busher (top/ left) is a Research Fellow at Coventry University.

Joel Busher (top/ left) is a Research Fellow at Coventry University.

Tufyal Choudhury is an Assistant Professor in the School of Law at Durham University.

Paul Thomas is Professor of Youth and Policy at the University of Huddersfield.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.