Fat-shaming: Change4Life’s anti-obesity ‘nudge’ campaign glosses over social inequalities

The Change4Life campaign draws on ‘nudge’ theory to encourage families to ‘make better choices’ about their diet and exercise. But, argues Jane Mulderrig, behavioural economics is a poor substitute for radical state intervention that would address the root causes of obesity – such as poverty, the availability of cheap junk food and inadequate public transport. Instead, Change4Life’s advertising subtly evokes northern, working-class families and plays on parental guilt using dubious science.

A Change4Life bus in Manchester. Photo: Firing up the quattro… via a CC-BY 2.0 licence

The rise of populist politics is sending shockwaves through advanced liberal democracies. Some commentators have diagnosed these developments as a protest at governments’ failure to address social inequality – partly because of fiscal austerity, and partly because a creed of free market competition which fears regulatory interventions (even to curb industrial practices that are demonstrably harmful, like the over-production of cheap fat and sugar-laden foods).

Unwilling or unable to pay for the spiralling (health and other) costs resulting (directly and indirectly) from these social inequalities, governments eschew social investment in favour of social blame. It is in this context that the ‘nudge’ concept has gained currency among political elites in the UK and elsewhere. Its use in anti-obesity policy has been of doubtful efficacy and dubious morality – and it subtly reinforces lines of social inequality through its policy messages.

‘Nudge’ draws on the theory of behavioural economics developed by psychologists Amos Tversky and Daniel Kahneman in order to shape civic behaviours towards more desirable ends while retaining individual freedoms. Rejecting the idea of the citizen-consumer as ‘rational utility maximiser’, behavioural economics argues that irrationality, bias, and just plain laziness play a key role in shaping our decision-making behaviours. Chicago academics Richard Thaler and Cass Sunstein propose its application to public policy as the ‘real third way’, designed to ‘help the less sophisticated people in society while imposing the smallest possible costs on the most sophisticated’.

In effect, this approach diagnoses widespread social problems (obesity, ill-health, poverty, criminality) as being in large measure a matter of individuals’ irrationality and inability to make decisions which are in their own and society’s best interests, thereby effectively posing a risk to the (social and economic) security of nations. As political strategy, nudge seeks to persuasively articulate this diagnosis of the problem and to then exhort (certain) individuals to wrest control back from the clutches of their ‘inner lizard’.

The UK government has pioneered this approach, with psychologist David Halpern acting as advisor to Tony Blair and subsequently commissioned by David Cameron to set up a new Behavioural Insights Team in the Cabinet Office. Now jointly owned with the innovation charity Nesta, the team has developed a range of policy interventions designed to enable people to make the ‘right’ choices. Such interventions range from changing default options (e.g. pension enrolments or organ donations) to the use of carefully crafted messages with ‘government acting as a more effective ‘persuader’ [in the context of] an agenda of enhanced personal responsibility’.

The Change4Life TV adverts

In this analysis, rising obesity is seen as a social problem which is ‘on the move’ and must be stopped before it reaches ‘epidemic’ proportions. This is the politics of futurity, of pre-emption. The prime policy targets, therefore, are future potentially obese adults – today’s children. Anti-obesity policy in effect construes children as a disease risk. More specifically, in the case of the ‘Change4Life’ social marketing campaign, it is northern working class children who are construed as the threat, whose risky lifestyle behaviours should be recalibrated – presumably to match those of the middle classes.

This targeting of a specific social demographic is accomplished very subtly, through voice and language style in a long-running TV campaign comprising short cartoon adverts. They offer the viewer a window into the lifeworld of the ‘typical family’ whose unhealthy lifestyles are acted out by colourful plasticine characters (courtesy of Aardman Animations, creators of Wallace and Gromit). The formula is repeated throughout the 23 adverts that have been broadcast since 2009: a voiceover delivers a confessional narrative about their unhealthy lifestyle involving too little exercise and too much (junk) food. This is then diagnosed as a policy problem by drawing on a biomedical discourse about the disease risks of such a lifestyle (Type 2 diabetes, cancer, heart disease). The policy solution in each case constitutes a suggested behaviour change (eating less and exercising more) accompanied by various incentivising merchandise (branded stickers, charts, recipes, vouchers) available if viewers sign up to the Change4Life website – a key metric in the campaign’s success.

Change4Life claims to be a collective, national movement, but subtly targets an already disadvantaged social demographic. The ‘confessional’ narrator in the adverts is one or more children (or adults, in the case of alcohol consumption). The accent is in most cases typically Yorkshire (in some closer to Lancashire); the language informal and colloquial. Both regions have among the highest prevalence of obesity by local authority in England. The ads end with a different voice (the symbolic ‘voice of government’) marking the transition back to the ‘real’ world of the viewer through direct address, exhorting us to ‘(sign up to) Change4life, now’. Throughout these adverts the use of personal pronouns ‘we’ (whose reference, semantically, often includes the viewer) encourages identification with the narrative, drawing the listener into the problematised lifestyles, while direct address (‘you’) invites active engagement with this ‘collective movement’, in a discourse which belies what is actually a decidedly individualistic framing of obesity.

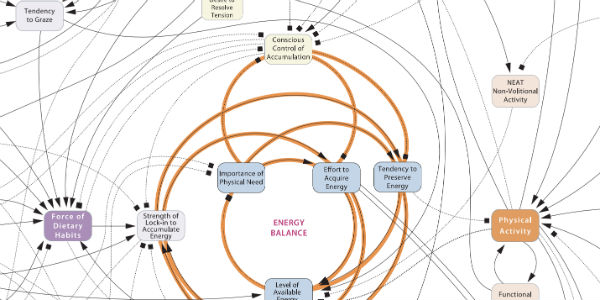

Change4Life contributes to the persistence of an ‘individual blame’ approach to public health by distorting and simplifying scientific evidence on the ‘systemic’ nature of rising obesity. The adverts reframe in simplified, emotionally manipulative language the obesity health risks proposed by the epidemiologists who authored the 2008 ‘Foresight’ report. The report uses an ‘obesity systems map’ to explain the diverse environmental, biological and socioeconomic factors that coalesce in producing increased obesity prevalence. Nevertheless it places the individual victim of ‘passive obesity’ at the centre of this system, locking her into psychologically entrenched behaviours. This invites the case for a lifestyle nudge and limits governmental responsibility for addressing the socioeconomic causes of obesity to the realm of individual behaviour change.

The centre of the Obesity Systems Map. Public domain

Foresight also uses statistical modelling to predict the health consequences among the adult population, while acknowledging uncertainties about the implications of childhood obesity for later life. Change4Life nevertheless places children centre stage in its framing of obesity as a threat to society and is accompanied by a national child measurement programme. The adverts deliberately avoid discussing ‘obesity’, as this was considered to be potentially alienating, and instead talk about ‘fat in the body’. This permits the distortion of scientific claims. The primary category of calculation in the Foresight report is ‘obesity’ and future prevalence (by 2050) is cautiously predicted at 25% of those under 20. The adverts, in contrast, claim that ‘9 out of 10 kids today would grow up with dangerous amounts of fat in their bodies’. Despite the acknowledged uncertainties about future trends, this claim is forceful in its certainty – no ‘could’ or ‘might’ here; rather ‘we woke up and realised that’. This is a much more shocking claim and is possible because it does not specify the age range involved and expands the category of calculation from the (relatively) well-defined ‘obesity’ to the ill-defined ‘dangerous levels of fat’. Distortions of this kind are interwoven with emotionally manipulative language about ‘horrid diseases’ and ‘loving our kids’, thereby invoking parental fears and guilt and feeding into wider societal anxieties about the most fundamental and intimate aspects of daily life: parenting, eating, health and wellbeing.

The ‘Obesity Systems Map’

Change4Life’s subtle targeting of a northern (poorer and statistically more obese) demographic implicitly acknowledges the social inequalities reflected in obesity, even as it focuses on individualised, rather than systemic, policy solutions. At the same time the government continues to view regulatory mechanisms on the food and drinks industry as a ‘last resort’, and shows even less interest in programmes of public investment (e.g. in urban planning, regional development, transport) to address the social inequalities underlying the uneven distribution of obesity.

Health policy has traditionally viewed obesity as a matter of individual (ir)responsibility, feeding into the liberal assumption that our greatest responsibility is to ourselves and those with whom we have the closest (kinship) ties. Change4Life fits with this view, making a very direct and personalised appeal to parents and their children. In reality, however, personal and societal well-being are more intertwined and complex than this, intersecting with a huge diversity of public and private practices (e.g. charitable giving to food banks, corporate social responsibility, ethical consumption, free school meals, community ‘green space’ initiatives, urban planning etc), as well as the largely unregulated over-production and marketing of profit-rich, nutrition-poor foods. And the elephant in the room of any policy debate about obesity is the stark increase in social inequality and child poverty. As the new chair of the Royal College of GPs, Dr Helen Stokes-Lampard, reminds us, health policy often overlooks the realities of people’s lives in which many cannot afford (and may not even have the facilities to cook) the fresh, healthy foods recommended in health campaigns of this kind.

With its emphasis on individual psychology, nudge offers governments a licence to reject fiscally expensive policy solutions to this systemic social problem in favour of individualised interventions to ‘help the less sophisticated’. Through colourful cartoons, inclusive, simplified, and emotionally manipulative language, it enlists children as the ‘instigators’ of family lifestyle changes. Meanwhile the health, diet and therapy industries make billions from our malaise, anxiety, low self-esteem and ‘unhealthy’ behaviours.

For a more detailed treatment of this subject: Jane Mulderrig (2016) ‘Reframing Obesity: a Critical Discourse Analysis of the UK’s first Social Marketing Campaign’, Journal of Critical Policy Studies

Jane Mulderrig is a Lecturer in Applied Linguistics and Director of the Applied Linguistics MA at the University of Sheffield.

Jane Mulderrig is a Lecturer in Applied Linguistics and Director of the Applied Linguistics MA at the University of Sheffield.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

[…] Fat-shaming: Change4Life’s anti-obesity ‘nudge’ campaign glosses over social inequ… […]