Time’s running out: Brexit scrutineers Hilary Benn and Angus MacNeil need to get a move on

Hilary Benn and Angus MacNeil are now in charge of the two most important of the many parliamentary committees scrutinising Brexit. Sophie Wilson urges them to act quickly. The Departments for Exiting the EU and Trade are already hard at work, and only 17 sitting weeks remain before the March deadline for Article 50 to be triggered. And getting out of Westminster to talk to people around the country – and abroad – should be a priority for committee members.

The Foreign Affairs Committee at work in 2011. Photo: Catherine Bebbington via Parliamentary copyright

Hilary Benn (Labour) and Angus MacNeil (SNP) have been confirmed as chairs of the two new select committees scrutinising the Department for Exiting the European Union (DExEU) and the Department for International Trade (DIT) respectively. These are two of the most influential positions in Parliament today, running the committees charged with holding the government to account as the UK leaves the EU and pursues trade deals with the rest of the world.

Both Benn and MacNeil need to get a move on. These committees are already on the back foot, starting work a full four months after the departments they are responsible for scrutinising. The ExEU Committee is likely to have only 17 sitting weeks in Parliament before the March deadline the Government has set to trigger Article 50. They must also avoid duplicating the work of other committees that have already started scrutinising the implications of Brexit in their policy areas. This will be no mean feat with 31 parliamentary inquiries already underway.

To be effective, it will be vital for the committees to agree their priorities and plan how they want to have an impact from the start. There are at least five areas Benn and MacNeil will want to focus on as they begin their work:

- Understand the impact of Brexit. Gathering evidence from businesses, charities and representative groups across the UK about the implications of Brexit will strengthen the government’s evidence base and help ensure the UK’s negotiating position is informed by a wide range of stakeholders, preventing any one perspective from dominating the agenda.

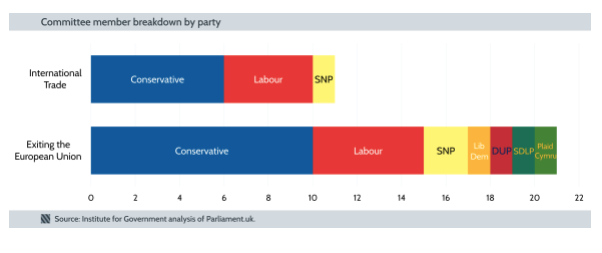

- Plan how to build political agreement. Both committees will have members from across the political spectrum, presenting an opportunity to build consensus around the priorities for Brexit. The committees could also develop networks with colleagues in the devolved legislatures, to draw their views into discussions and help maximise the chances of an agreed UK-wide position being reached.

- Consider how to make the most of the inquiry process. Committees will want to react rapidly to changing circumstances and will have to call ministers or civil servants as developments occur. Although the PM has resisted the idea she might provide a “running commentary” on negotiations to Parliament, the committees may wish to push for private meetings with ministers to discuss sensitive elements of the negotiation or for sight of confidential documents for scrutiny. This would facilitate Parliamentary oversight of one of the most complex and challenging tasks to face the government in decades. It would also help the government engage with Parliament, increasing the government’s credibility as a negotiating partner and avoiding the possibility of agreeing a deal that Parliament then rejects.

- Engage the public. Getting out of the Westminster bubble to talk to communities across the country would help guarantee a variety of views on the possible outcomes and implications of Brexit are heard. Holding open meetings or evidence sessions where members of the public are able to question experts and analyse evidence could enhance the public’s understanding of the Brexit process and politicians’ understanding of national preferences. Making use of social media and online discussion forums could also help focus the committee’s work on what people care about.

- Understand perspectives outside of the UK. Both committees may wish to engage in ‘parliamentary diplomacy’, travelling to Europe and beyond to understand the perspective of government, legislatures and other players in the countries with which the UK will be negotiating.

However, fulfilling these tasks effectively will demand additional resources. Not only will the committees need extra administrative support to organise visits within the UK and beyond, they will also want to make use of specialist advisers to help them grapple with the wide-ranging complexities involved in Brexit. Ensuring they have the resources needed to conduct inquiries within tight timescales should be a vital priority for the new chairs. Without this, they will find it difficult, if not impossible to perform their role.

But for now, both men will have to wait for the election of committee members – processes which will be conducted separately by each political party over the next few weeks. Once their members are in place, the two committees will need to get off to a running start if they want to cement the reputation of their committees and make a meaningful contribution to the Brexit process.

This post represents the views of the authors and not those of Democratic Audit.

Sophie Wilson is a researcher at the Institute for Government.

Sophie Wilson is a researcher at the Institute for Government.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

New committee members announced – @democraticaudit explains what they should be thinking about next:… https://t.co/0750wAqjHv

[…] This post represents the views of the author and not those of LSE Brexit. It was first published at Democratic Audit. […]

Time is running out for the Brexit scrutineers my blog for @democraticaudit on what select comms need to do next… https://t.co/HVa5fgIdtC

A timely piece, the content and nature of which you will look for elsewhere in vain. And yet this is where Parliament could prove itself in the process of the UK leaving the EU.

One major danger is with Area Number 1 (understanding the impact of Brexit). Will this just be re-run of the campaign, shorn of the embarrassing (and for-one-campaign-only) claims that on the day after the referendum massive tax cuts will be needed and pensions will have to be slashed. That horse has bolted and vanished from view, but there are others like it, slightly weary but willing, waiting in the Remain stable – if this area is not to be hijacked by special pleading (and therefore made useless by further hysterical and similar claims of armageddon like those made by Remainers before 23 June), any points made have to be properly scrutinised – and that means it is not enough just to ask a couple of well chosen ‘experts’ who may have vested interests or be in the pocket of a government which does not really wish to leave the EU.

To simply suggest, once again, that there are ‘black clouds just around the corner’ is to invite cynicism of Parliament as captured by an elite looking back at the sunlit uplands of 6 months ago where the never ending joys of domination by the EU looked set to last forever (well for the rich and the elite, at least).

During the campaign, a woman reported to a focus group that she had been in her local hairdressing salon and the tv was on. The UK Chancellor (finance minister) Osborne came on and outlined with a near straight face the many thousands of pounds that all the poor little pensioners would lose if they dared vote against the government…and the woman reported that everyone in the salon burst out laughing.

Says it all does it not? Like Ceausescu on the balcony, once they start laughing at you you’ve had it. If Parliament does this trick of laying on armageddon thick as part of its ‘scrutiny’, it will lose further credibility. If it rises above its natural inclination to use its role as Chief Mourner for the EU to bash the country’s prospects, and if it looks genuinely dispassionately at what could or could not happen, it role will be enhanced.

Brexit scrutineers Hilary Benn and Angus MacNeil need to get a move on, says @sewilso – DExEU is already planning https://t.co/ZNFF3tNZnP

Time’s running out: Brexit scrutinisers Hilary Benn and Angus MacNeil need to get a move on via @democraticaudit

#… https://t.co/LyQp8hwzci

Time’s running out: Brexit scrutineers Hilary Benn and Angus MacNeil need to get a move on https://t.co/HpVsGR8KWq

Time’s running out: Brexit scrutineers Hilary Benn and Angus MacNeil need to get a move on https://t.co/RhGS8fmz4E

Time’s running out: Brexit scrutinisers Hilary Benn and Angus MacNeil need to get a move on https://t.co/ZNFF3u5Afn https://t.co/z1nrDJUn8Z