Justice outsourced: why Concentrix’s tax credit mistakes matter

Administrative justice issues rarely attract the attention they deserve. However, the recent revelations about the tax credit checks undertaken by Concentrix on behalf of HMRC – and the poor service inflicted upon people – highlights a fundamental challenge to administrative justice posed by outsourcing and privatisation. Robert Thomas and Joe Tomlinson argue that the episode highlights the need for government to take administrative justice more seriously when it contracts out important tasks to private companies.

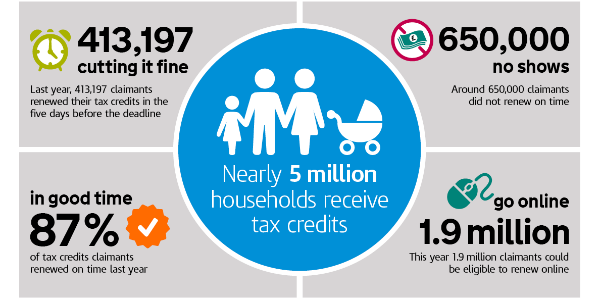

An HMRC poster from 2014. Image: HMRC via a CC-BY 2.0 licence

Tax credits are administered by HMRC. For people on low incomes, they are critically important and can mean the difference between surviving and not-surviving. In 2014, HM Revenue & Customs contracted out tax credit compliance checks to US company Concentrix. The policy goal is to reduce the amount of error and fraud. HMRC’s contract with Concentrix is worth between £55m-£75m. Concentrix has been sending letters to people in receipt of tax credits, requiring evidence, and then reducing individuals’ tax credits.

The following concerns are drawn from publicly available sources (see also here, here, and here).

- Tax credits being stopped for incorrect reasons. The concern is that people are being incorrectly punished because Concentrix has made wrong allegations and incorrect decisions. For instance, Concentric reduced one woman’s tax credits because it claimed that she was in a relationship with someone she had never met, a former tenant of her property. In another case, a young mother had her tax credits stopped after being wrongfully accused of being married to a 74 year old deceased man.

- Communication difficulties. Individuals have experienced acute difficulties in contacting Concentrix to query and challenge the reduction of tax credits. For instance, people have been calling Concentrix repeatedly and being put on hold. There have been complaints of individuals spending hours trying to contact Concentrix on the phone.

- Relevant evidence not being properly taken into account. Individuals have supplied relevant documents to Concentrix which are have then been ignored. For instance, a single parent working part-time was asked to provide evidence of childcare, which she did three occasions. Nonetheless, her tax credits were then reduced from £140 per week to £46 per week.

- Inadequate linking of data between HMRC and Concentrix. For instance, an individual supplies relevant information to Concentrix, which then updates its database. However, this does not automatically lead to HMRC’s database being updated, with the consequence that an individual will not necessarily receive their payments or receives a demand to repay the ostensible over-payment of tax credits from HMRC to the tune of £2,500. Being caught between two systems seems inexplicable given the advantages of modern IT.

- Unlawful reversal of the burden of proof. Letters sent by Concentrix have stated that individuals must prove that they are still entitled to tax credits. However, according to the Upper Tribunal, this is legally incorrect. In such circumstances, the burden of proof is not on the claimant. In an Upper Tribunal case, NI v HMRC [2015] UKUT 0490 (AAC), Judge Wikeley noted that both HMRC and the First-tier Tribunal had failed to apply the correct burden of proof – a basic legal error.

- Inadequate training of Concentrix staff. In 2015, The Independent reported that Concentrix staff were under pressure to open between 40 and 50 new tax credits investigations a day, and that decision makers, complaining of inadequate training, were encouraged to make three decisions an hour on whether to confirm, amend or stop tax credit claims. Clearly such pressures may lead to errors given the complexity of calculating tax credits correctly.

- Concerns raised by MPs. One MP has stated that Concentrix have cut people’s benefits in order to chase profits. Another MP, Craig Mackinlay, has noted that Concentrix’s decisions have contained an enormous volume of errors that have been catastrophic to people’s lives and that its performance has fallen far short of expectations.

The performance of Concentrix is clearly of intense concern in terms of the hardship for people affected. There are examples of fraudulent use of tax credits. A woman recently pleaded guilty to fraudulently claimed £47,500 in tax credits after failing to tell the authorities she was living with her police officer partner. The policy goal is then valid, but many people have been wrongfully accused of defrauding the system. This had led to unnecessary stress and anxiety.

Under its contract with HMRC, Concentrix is paid on a payment by results model on the basis of accrued savings from “correcting” tax credit claims. In other words, the more public money Concentrix saves by reducing tax credit payments, the more it gets paid. Conversely, Concentrix gets paid less if its decisions are wrong.

This payment model is directly relevant to the operation of the administrative justice mechanism, administrative review or “Mandatory Reconsideration” as it is known in the benefits context. People who want to dispute must ask Concentrix to review its own decision before they can go to the independent and judicial tribunal process. Administrative review is a key administrative justice function. In 2015, Concentrix made 370,000 decisions and received nearly 6,000 administrative reviews. No data is yet available on outcomes.

The payment by results model provides for adjustments for these reviews. In other words, reversing initial decisions has financial consequences for Concentrix because it means less reduction to tax credit payments. HMRC states that Concentrix is subject to stringent assurance checks. More data is required to investigate this issue further, but anyone could be forgiven for being sceptical.

On 13 September, HMRC announced that it would not be renewing the contract with Concentrix. Instead, tax credit compliance checks will be moved back in-house and undertaken by HMRC. This seems like a knee-jerk response to recent adverse media coverage of Concentrix. The episode highlights some fundamental issues concerning administrative justice.

First, privatising administrative justice poses a challenge because the profit motive may undermine justice for individuals. Established models of administrative justice – impartial administration; legal process; and professional judgment –are all underpinned by a public service ethos predicated upon the basis of impartial decision-making. This is so taken for granted that it is rarely articulated.

However, privatised schemes of administrative justice – such as Concentrix – challenge this principle. The profit motive and a payment by results approach may well undermine the principle of impartial and disinterested administration. In turn, this can undermine the acceptability of decisions. Privatised schemes of administrative justice are not necessarily illegitimate. Such schemes could operate to high standards of both justice and efficiency. But, that has clearly not happened here.

Second, there is a need for effective oversight of administrative justice, a task that is often fragmented amongst a range of oversight bodies. There needs to be more transparency about how privatised administrative justice works in practice. For instance, how many administrative reviews does Concentrix allow and how does this compare with ordinary government-administered benefits? Parliament and the National Audit Office should undertake closer scrutiny.

Third, there is the issue of administrative justice expertise. Many people both inside and outside government are therefore well-placed to advise on administrative justice issues. Yet government works in departmental silos. HMRC seems to have given little thought to administrative justice considerations when it outsourced to Concentrix. In light of this, it would only be appropriate for the Ministry of Justice to reconsider its decision to end the Administrative Justice Forum in 2017. If similar episodes are to be avoided in the future, then government needs to pay more attention to administrative justice issues and draw upon existing expertise.

This post represents the views of the authors and not those of Democratic Audit.

Robert Thomas is Professor of Public Law at the University of Manchester.

Joe Tomlinson is Lecturer in Public Law at the University of Sheffield.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Justice outsourced: why Concentrix’s tax credit mistakes matter : Democratic Audit UK https://t.co/ywVb3HdRj6

Justice outsourced: why Concentrix’s tax credit mistakes matter https://t.co/2yAAPt5RwT

[…] Administrative justice issues rarely attract the attention they deserve. However, the recent revelations about the tax credit checks undertaken by Concentrix on behalf of HMRC – and the poor servic… […]

Concentrix

WORKING TAX CREDITS

In this guide I will be concentrating solely on those people on Working Tax Credits who have had the misfortune to come to the attention of Concentrix (although those claiming Child Tax Credits may also find some of the items helpful).

The purpose of this guide is to ensure that you are protected as far as possible and that you have made all due efforts to comply with the requirements expected of you.

Please be aware that this is NOT meant to be a fully comprehensive guide and where possible you should seek independent legal advice as well as advice from other organisations like CAB etc.

Firstly, a little background;

Unemployment in the UK is at its lowest point for 15 years and this can strongly be attributed to Zero Hour Contracts and Self-Employment.

A great deal of people in this country are now regarded as self-employed, not in the way as was traditionally understood but in the way that they were “persuaded” to come off JSA and ESA to become “self-employed” due to bullying or the threat of sanctions etc.

All was “well” until HMRC found it fit to employ the American company Concentrix in May 2014 to “target fraud” in the Working Tax Credit and Child Tax Credit claiming population.

Concentrix was employed on a Payment by Result basis which simply meant that the more cases they closed down the more money they would be paid by the government. This has led to a great temptation to go for the “Low Hanging Fruit”.

This business was worth between £55mn and £75mn. Their contract was due to be renewed in May 2017 but this has now been cancelled but in the meantime Concentrix will continue to deal with the approximately 200,000 cases they still have in hand but will not be allowed take on any further new ones.

Dealing with Concentrix

For a lot of you, the first you would have heard of Concentrix is a letter that state that they have not received a reply to a letter they sent you some months earlier and they will therefore be amending your Tax Credits. There will be mention (or threats) of the possibility of penalties being charged. There will also be mention of you receiving a decision letter which will advise you about your Tax Credit awards and what to do if you disagree with their decision.

Around this time your Tax Credits would have suddenly ceased and you would have had to have made 50 plus fruitless calls to their number 0345 6003130 – which will 99 times out of 100 will be engaged.

You look for an email address for the company on their letterhead and maybe even searched on line for one. Strangely enough for an international financial company, they don’t have one!

IF you were LUCKY to get through you would have faced an incredibly long list of security questions which will include being asked for your bank details. Some of you who did manage to get through all of this would have sensibly refused to provide your bank information to this unknown company as It’s been drummed into you NOT to provide this information if you didn’t want to be a victim of fraud. The result is you failed the security checks and the call terminated.

Whilst on the phone to Concentrix you may be subject to provocation, try not to rise to it. Losing your temper and swearing will only result in your call being terminated.

It would now be obvious that, seeing your Tax Credit payments suddenly stop, a decision must have already been made. In spite of this fact, you don’t actually receive the promised Decision Letter. The reason for this is that you only have 30 days to appeal their decision from the date of the Decision Letter. After this time period you have NO RIGHT to appeal. (I will come back to this point later)

You would have tried ringing HMRC direct on their number 0345 300 3900 only to be told that yes Concentrix were working for them but they couldn’t help you because Concentrix were solely responsible for dealing with your case.

You ask them what was in the mysterious letter that “was sent” to you those months previously. They will confirm that their records show that Concentrix state a letter was sent to you. You ask “if it’s possible for HMRC to send you a copy then?”

NO it isn’t.

In the meantime, you have no money and are getting increasingly desperate and just when you think things couldn’t get worse you receive a letter from HMRC demanding the money back they’ve paid you so far this financial year.

You ring HMRC again to ask why? Simply that you’ve been “over paid” and they want their money back. You ask for their help again as you still haven’t been able to get into contact with Concentrix. Once again the answer is no. You are once again directed back to Concentrix as only Concentrix are dealing with your case. If that is the case you ask, why are YOU at HMRC demanding money from me. Same answer, you’ve been over paid.

NOW, even if you have already written to Concentrix you MUST write to Concentrix again immediately and include ALL of the following;

• Write to Concentrix to the address on their letter,

• Quoting their case number

• Quote your NI Number and request a copy of their previous letter.

• VERY IMPORTANT in your letter you MUST request that they carry out a mandatory reconsideration of their decision.

Time is critical here, if the mandatory reconsideration request isn’t sent within 30 days of the Decision Letter supposedly being “sent” to you, you’ve lost your right of appeal. So SEND it NOW

You MUST copy in your HMRC office and send both letters RECORDED DELIVERY and make sure you keep these proofs safe. (You will need them later)

In the meantime, keep trying to contact Concentrix by phone.

After 10 days of the date of sending your letter (and assuming you haven’t received anything from Concentrix by post whether you’ve managed to get through to them on the phone or not) send a second letter titled “Second Request” referring to your first letter and following all the instructions above.

If you ARE in communication with Concentrix, make sure you always copy in HMRC in all your communications with them (that’s correspondence only, NOT copies of documentation and receipts etc. requested by Concentrix)

It is important to remember that regardless of whatever HMRC tell you on the phone, HMRC are ultimately responsible for ALL your tax affairs NOT Concentrix who act purely as their agents.

It’s now another 10 days since your last letter and you’ve still not heard anything and still haven’t been paid. So what now?

I have my own personal ideas but at this stage we have to make our own minds up. One recommendation that I can give you though is that wherever you can, please try to enlist the help of your MP.

If you can do all that you will have made all due efforts to comply with the requirements expected of you.

Good Luck.

See our piece on Concentrix today https://t.co/CH5sf3H9Ap https://t.co/4bqNs1h1s1

Administrative justice doesn’t get the attention it deserves. The Concentrix debacle shows why it matters https://t.co/CH5sf3H9Ap

More about Concentrix here. Never get a cartoon Gaul to run a tax agency.

https://t.co/Fpk7jg31ea

Justice outsourced: why Concentrix’s tax credit mistakes matter https://t.co/m2JsO55nfV

Justice outsourced: why Concentrix’s tax credit mistakes matter – Democratic Audit UK https://t.co/KfLpzAQAdr

Justice outsourced: why Concentrix’s tax credit mistakes matter – Democratic Audit UK https://t.co/BsDNBc0aea

Justice outsourced: why Concentrix’s tax credit mistakes matter https://t.co/932CMNrpAL

Justice outsourced: why Concentrix’s tax credit mistakes matter https://t.co/CH5sf3H9Ap https://t.co/jC2prjF0ft