This May be Tory feminism: The second woman PM is not Margaret Thatcher Mark II

As the second Conservative Prime Minister, it is hardly surprising that Theresa May is being compared to Margaret Thatcher. But Julie Gottlieb writes tracing the political ancestry on the basis of their common gender is misleading. In particular, she highlights May does not share Thatcher’s apparent rancour for feminism, and argues that we could be on the brink of discovering how feminist Toryism can work in practice.

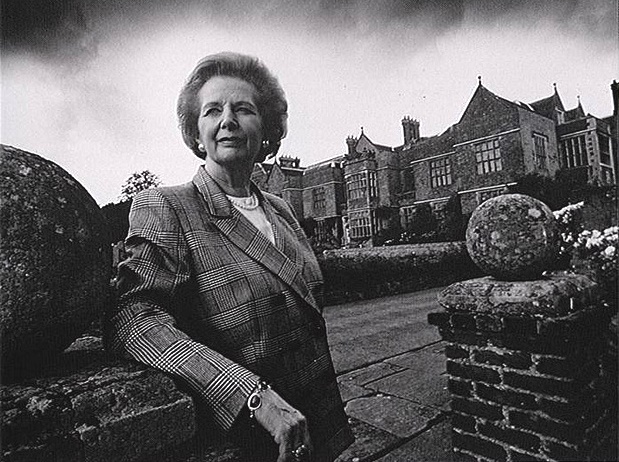

Is Britain’s second woman Prime Minister really the direct heir to Margaret Thatcher? Theresa May has certainly been represented as such, and she has been measured against Thatcher’s towering but also heavily tainted legacy. The day before May walked into No. 10, Metro (Tuesday 12 July 2016) placed their vital statistics side by side in “Maggie V May: How They Compare.” The Thatcher factor looms large.

The comparison will no doubt be made when such a rare and remarkable milestone is reached. There will inevitably be points in common between these two women who defied the odds to rise to the top job in their party and to the top job in the nation.

Nonetheless, there are quite significant differences between the two, and tracing the political ancestry on the basis of their common gender is misleading. A generation plus apart, May is not Thatcher’s imitator in the field of gender politics—she is not Margaret Thatcher mark II.

We can accept hybrid political concepts like Tory democracy, One Nationism, and compassionate conservatism, or that neoliberals can counterbalance economic conservatism with social progressivism (Cameronian Conservatism, in fact). So why do we find it harder to fathom Tory feminism? Both feminism and contemporary conservatism of the pragmatic-opportunistic variety are more protean than might be expected.

May does not share Thatcher’s apparent rancour for feminism. Thatcher was more than a let-down as the first woman PM from the point of view of the Women’s Liberation Movement—she was a disaster. The Iron Lady called feminism a poison. She felt under no pressure to foster sisterhood or promote women. Only one woman was appointed to her Cabinet, the Baroness Young. ‘Attila the Hen’, as François Mitterrand called her, was only really at ease in the company of men.

Beatrix Campbell’s brilliant The Iron Ladies: Why Do Women Vote Tory (1987) exposed Thatcher’s contempt for other women, and the ways in which she reserved power and greatness for herself. But as Campbell also showed, paradoxically, this did little to threaten women’s electoral support for her party.

In contrast, Theresa May is as comfortable in her kitten heels as in the t-shirt of Fawcett Society (“this is what a feminist looks like”). Her newly formed Cabinet has the most women of any previous Conservative administration. May has other feminist-friendly credentials too: she co-founded with Baroness Jenkin Women 2 Win in 2005; she was Minister for Women and Equalities (2010-12); she was entrusted with one of the key Cabinet posts by David Cameron who as PM made deliberate efforts to promote women within the Tory frame. (But it is also true that women are also given the opportunity to stand in unsafe or unwinnable seats).

May is the product of her baby-boom generation where what is anathema is not feminism and the discourse of sexual equality. Rather it is old-school, old-boy homo-social sexism that catches the headlines.

Andrea Leadsom’s clumsy playing of the mother card, and her sexual politics generally, was perceived to be at odds with the zeitgeist, and effectively put paid to her campaign to be the second woman Prime Minister—a remarkable riposte to the ‘traditional values,’ ‘family values’ of Thatcherism.

There is a longer history of Tory feminism that helps to explain May and, in fact, suggests Thatcher may actually be the anomaly.

A number of Tory women were prominent suffragists, and Louisa Knightley founded the Conservative and Unionist Women’s Franchise Association in 1908. Conservatives were represented among the suffragettes as well, with Lady Constance Lytton as one example, and WSPU-donor Lady Lucy Houston, simultaneously a diehard feminist and ultra-Tory imperialist and defencist. Edith Lady Londonderry and Thelma Cazalet-Keir were two Tory suffragists who became important figures within the party between the wars.

In the party’s transition to mass democracy it formed the mixed-sex Primrose League in 1883 and, after suffrage, the Women’s Unionist and later Women’s Conservative Associations endowed women with significant social power. Campbell could start answering the question ‘why do women vote Tory’ by studying the effectiveness of the feminised party machine. With a membership of one million in the 1930s, the CWA was instrumental to the party’s electoral success.

In 1919, the first woman MP to take her seat was the Conservative, American-born Nancy Astor, and throughout her twenty-six years as Plymouth’s MP she eagerly embraced her role as the representative of all women.

While there was only a handful of women MPs in those first decades after the First World War, many of the Conservative ones self-identified as feminists (by the measure of their time), and scored firsts for women in national and international politics, and in the rituals of parliamentary democracy.

One can understand why the present-day Conservative Women’s Organisation takes pride in a feminist pedigree. A number of former-suffragettes eventually found their political home on the Right, including WSPU leader Emmeline Pankhurst who joined the party before her death in 1928.

That it was Margaret Thatcher who became the first woman PM meant that this story, this strain of a feminised and even feminist Toryism, was sweep aside. It did not help to explain the advent of Thatcher.

But May, as the second woman Conservative PM, needs to be set against a rather different historical backdrop. We have yet to see how well feminist Toryism can work in practice, and whether May will succeed to ‘iron’ out the obvious inconsistencies and ‘iron’ in a new ethos to the social and intellectual fabric of the Conservative party.

—

Note: this post was first published by The Huffington Post on 19 July 2016 and also appeared on the PSA blog. It is cross-posted with the author’s permission and represents the views of the author and not those of Democratic Audit or the LSE. Please read our comments policy before posting.

—

Julie Gottlieb is Reader in Modern History, University of Sheffield. She tweets @JulieVGottlieb.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

This May be Tory #feminism: The second woman PM is not Margaret Thatcher Mark II https://t.co/iuxJHGDNpi

This May be Tory feminism: The second woman PM is not Margaret Thatcher Mark II https://t.co/UP3rFRlEmB

This May be Tory feminism: The second woman PM is not Margaret Thatcher Mark II https://t.co/gsV94TJSuA

This May be Tory feminism: The second woman PM is not Margaret Thatcher Mark II https://t.co/qMxygjtQtJ

This May be Tory feminism: The second woman PM is not Margaret Thatcher Mark II – Democratic Audit UK https://t.co/FJo35pM4cI

[…] This May be Tory feminism: The second woman PM is not Margaret Thatcher Mark II. As the second Conservative Prime Minister, it is hardly surprising that Theresa May is being compared to Margaret Thatcher. But Julie Gottlieb writes tracing the political ancestry on the basis of their common gender is misleading. In particular, she highlights May does not share Thatcher’s apparent rancour for feminism, and argues that we could be on the brink of discovering how feminist Toryism can work in practice. Credit: BBC R4 CC BY-NC 2.0 Is Britain’s second woman Prime Minister really the direct heir to Margaret Thatcher? […]

This May be Tory feminism: The second woman PM is not Margaret Thatcher Mark II https://t.co/VwGR1PtB5L https://t.co/LZxy6GjCpL