Opponents of populism will never win the argument by defending an unreformed, adversarial 20th century form of democracy

As liberal democracy degenerates into technocracy on the one hand and demagoguery on the other, Claudia Chwalisz writes participatory and deliberative mechanisms are crucial to the defence of a pluralist, tolerant society.

From Italy to Spain to Iceland and the UK, this week will witness elections and referendums pitting ‘the people’ against ‘the establishment.’ A mayor of Rome from the Five Star Movement, a Spanish governing coalition with Podemos at the helm and an Icelandic Pirate Party presidency are all possible. While they differ on policy ideas, the uniting factor is a rejection – not entirely unjustified – of corrupt elites and dangerous ‘others’ (usually immigrants and EU technocrats) and a defence of direct democracy, notably the use of referendums.

Taken together with the nativist far right governments in Poland and Hungary, the nomination of Donald Trump in the Republican primaries, the looming fight between Marine Le Pen and Nicolas Sarkozy to be the true defender of ‘the French people’, and the near-election of an Austrian far right president, the bigger threat, of liberal democracy disintegrating, looms. In many countries, it is already splitting away into illiberal democracy and undemocratic liberalism, each in their own way claiming to give ordinary people a voice and to take power away from the elites, intellectuals and technocrats.

On the one hand, illiberal democracies have elected representatives, but they are stripping people of their rights to freedom of the press, of the checks and balances on power (weakening the power of constitutional courts), and of minority and human rights. Undemocratic liberalism, on the other hand, means those rights are left intact, but the notion of ‘free and fair elections’ deciding the will of the people has become a farce. Increasingly, governments have been manoeuvred by the populist fringe into holding referendums.

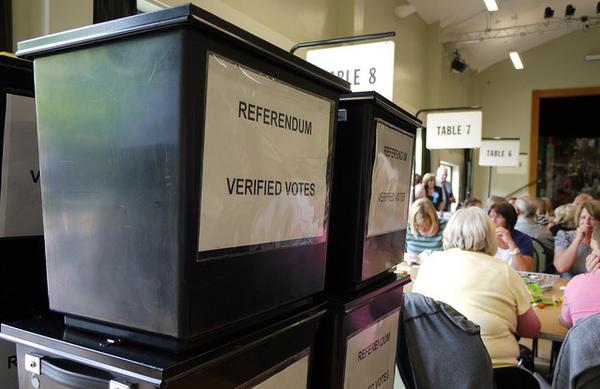

In the UK, we are witnessing for the second time in two years why populists love referendums as a tool for ‘giving power to the people.’ Complex, difficult problems are boiled down to binary, simple choices – ‘yes’ or ‘no’ to Scottish independence; ‘remain’ or ‘leave’ the European Union (EU). In both cases, what would happen in the case of a vote against the status quo is muddled and undefined. In this vacuum of clarity, campaigners from all wings of the political spectrum propose their own, often contradictory, utopias.

One might wonder whether the details of the UK’s relationship to the EU would baffle most voters. Recent Ipsos Mori polling suggests that it does. In a survey of 1,000 people weighted to represent the UK’s demographic profile, respondents overestimated the number of EU migrants to the UK, overestimated the UK’s contribution the EU budget, overestimated the amount of child benefit payments to EU migrants, and overestimated how much the EU spends on administration. Only five per cent of people were able to name their MEP.

This high level of ignorance suggests one of the reasons why, to quote the former prime minister Clement Attlee, referendums are ‘un-British’ and a “device of dictators and demagogues.” A referendum is not usually a true sounding of people’s rational thinking or a check of their expertise. The questions are often on issues that most people do not have the time or resources to consider themselves. As we are witnessing in the UK, referendums are often about gut feelings, easily manipulated.

But we should not ignore that this latest vogue of referendums is merely one reflection of the growing mistrust in elected political representatives, one that is not limited to the four countries discussed at the start of this piece. Political alienation is a fertile breeding ground for populists. The feeling that ordinary people’s voices do not count in political decision-making is genuine, and should be acknowledged. When people start to feel like they are no longer masters over their own fate, populists claiming to give back power to the people start to resonate. Yascha Mounk rightly points out that “for all intents and purposes, [citizens] now live under a regime that is liberal, yet undemocratic: a system in which their rights are mostly respected but their political preferences are routinely ignored.”

This undemocratic liberalism seems to be the slippery slope towards illiberal democracy, down which Hungary and Poland have already fallen. It is not a dilemma limited to central Europe either; the real potential for Donald Trump and Marine Le Pen to be elected as presidents of the United States and of France highlight the transatlantic nature of the phenomenon.

Arguably, there is another way in which widespread anti-establishment anger can be softened without branching into either illiberal democracy or undemocratic liberalism. Society need not be divided by fear-driven anti-pluralism. This requires considering democracy as more than just elections and political parties. Democratic innovations that engage citizens (as opposed to elected representatives or organised interest groups) directly in the public decision-making process should play a greater role in the way we solve our collective problems.

Used in a growing number of countries, long-form deliberations such as citizens’ juries and citizens’ reference panels allow elected politicians to make decisions in more genuinely democratic ways. Randomly selected citizens are brought together numerous times to become better informed, to deliberate with one another, and to propose serious recommendations.

The best examples are arguably from Canada and Australia, where these methods have now been used around 50 times in the past six years alone – on important issues ranging from physician-assisted dying, to determining 10-year city plans, grappling with the best ways to tackle obesity, and considering 30-year infrastructure investments among others. The growing list of cases shows that it is possible to make trusted public, democratic decisions which represent the informed general will of the people.

The opponents of populism will never win the argument by saying ‘you’re wrong’ and defending an unreformed, adversarial 20th century form of democracy. There must be a willingness to acknowledge that more profound structural changes to our democratic institutions are necessary to meet the needs of our communities. The risk of losing the community’s commitment to democracy is great, and in some places, it is already underway. Democratic innovations [RT1] are not a silver bullet, but they are one way to reconcile and re-educate people to democracy.

At the same time, we must not lose the argument about liberalism either. For, as defined by Edmund Fawcett in his great tome on Liberalism, the “acknowledgement of inescapable ethical and material conflict within society, distrust of power, faith in human progress, and respect for people whatever they think and whoever they are” are principles for which people have fought and died for centuries. They should be defended, and must not be taken for granted.

__

This article originally appeared on Renewal with the title “Can liberal democracy be rescued?” It represents the views of the author and not those of Democratic Audit or the LSE. Please read our comments policy before posting.

__

Claudia Chwalisz is the author of The Populist Signal: Why Politics and Democracy Need to Change (Rowman & Littlefield 2015) and a commissioning editor for Renewal.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Opponents of populism will never win the argument by defending an unreformed, adversarial 20th c form of democracy https://t.co/eAgSgtwpNM

Opponents of populism will never win the argument by defending an unreformed, adversarial 20thC form of democracy https://t.co/v2oCgKKRB7

Opponents of #populism will never win the argument by defending an unreformed, adversarial 20th c form of democracy https://t.co/ixuJVt4eoK

Curing populism with deliberative democracy? Somewhat correct diagnosis, but wrong cure, I’m afraid…

https://t.co/PB32pbhOya

Opponents of populism will never combat it by defending an unreformed, adversarial 20th century form of democracy https://t.co/uUXQHIbqhf

Opponents of populism will never win the argument by defending an unreformed, adversarial 20th C form of democracy https://t.co/MTaLCP1W4S

Opponents of populism will never win the argument by defending an unreformed, adversarial 20th c form of democracy https://t.co/atRq4WuCfi

Opponents of populism will never win the argument by defending an unreformed, adversarial… https://t.co/B5SCYw3nPU https://t.co/oTPtEB74n6