The number of party mergers is likely to increase in advanced democracies

Many of the important political parties in European democracies today (including the UK Liberal Democrats) resulted from the permanent unification of smaller parties. Such mergers can have major consequences on party competition, electoral outcomes and government formation. Raimondas Ibenskas discusses the results of a recent comparative study on party mergers in 24 European democracies by analysing their costs and benefits for political parties.

Paddy Ashdown of the Liberal Democrats – (Credit: thor Rodhullandemu via Wikimedia Commons)

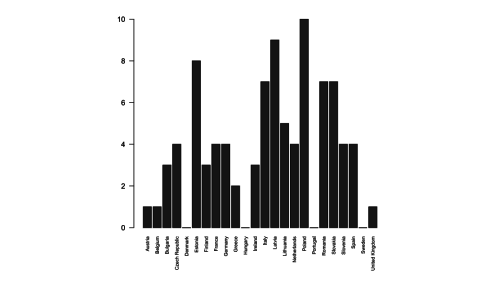

Mergers of large business corporations often make it to the news headlines, as illustrated by the recent example of the potential merger between the London Stock Exchange and Deutsche Börse. However, far less is known about the mergers of ‘service suppliers’ in the ‘political market’ – that is, political parties (but see here, here and here). This is surprising given that mergers can have major consequences on the patterns of party competition, electoral outcomes and government formation. Also, as Figure 1 shows, party mergers are not that rare as commonly thought. According to the new dataset I gathered and used in my recent publication in the Journal of Politics, in the post-war period almost every of the 24 European democracies analysed had at least one merger that involved two or more parties with at least 1 percent of the popular vote. A number of important parties in Europe today are the result of the integration of two or more smaller party organisations including the Socialists and Republicans in France, the Left Party in Germany, Syriza in Greece, the Democratic Party in Italy, the Green Left, the Christian Union and the Christian Democratic Appeal in the Netherlands, the Law and Justice in Poland, the National Liberal Party in Romania, and the Popular Party in Spain. The UK fits this broader pattern quite well as one of its nationally-important parties – the Liberal Democrats – was formed through the fusion of the Liberals and the Social Democrats in 1987.

Figure 1: Number of party mergers in Europe in the post-war period

Why then do political parties merge? And how likely are party mergers in the future? To answer these questions, my research identifies the key costs and benefits of mergers to political parties. I summarise my arguments in the remainder of this post.

Costs of mergers

As recurring media reports about possible mergers between the Liberal Democrats and the Labour or the Conservatives and the UKIP indicate, mergers are more frequently on politicians’ minds than their actual numbers would suggest. This implies that usually their costs are too high for parties to even consider them seriously let alone starting negotiations with potential partners. Specifically, I find that the most important costs concern the ideological and policy differences that constituent parties need to overcome before they can formulate a coherent programme of the merged party. Consequently, in contrast to government coalitions, the mergers between the parties that are far away from each other on the ideological spectrum are highly unlikely.

Apart from ideological differences, established party identities also present an obstacle to mergers. Mergers of such parties are likely to lead to the defection of their activists and voters because ‘their’ parties disappear or are radically transformed. Using party age as a proxy for the strength of party identity, I find that older parties are substantially less likely to merge. The comparison between two young liberal parties in Lithuania (the Liberal Union and the Centre Union) that merged in 2003 and their two older counterparts in the Netherlands (the People’ s Party for Freedom and Democracy and D66) that considered a merger in the mid-2000s illustrates the importance of voter and member attachments to party organisations. Being founded in the early 1990s, neither of the two Lithuanian parties had strong partisan following in the electorate, which resulted in their wildly fluctuating electoral fortunes in the period between 1992 and 2000. Thus, the risk of partisan backlash by voters was limited. In contrast, the widespread dislike of the VVD and the merger idea itself by the voters and members of D66 and, to a smaller extent, different organizational cultures of the two parties, were key reasons for why the merger did not take place despite their similar programmes.

Another type of costs concerns the time and effort that the leaderships of the constituent parties need to spend on achieving and implementing merger agreements on the policy of the merged party, the division of office positions in it, and the integration of constituent party organisations. Parties can extend these costs in time by participating in government coalitions or presenting joint candidates or candidate lists in the elections prior to the merger. Trust established by previous cooperation also decreases the risk of the defection by a larger partner after the merger through, for example, the redistribution of office positions or the unilateral shift in the united party’s policy positions. Thus, out of 94 mergers analysed in my sample, parties previously cooperated in electoral alliances in 48 cases. 20 mergers were preceded by the participation in the same government coalitions in the electoral term prior to the one in which a merger occurred.

Benefits of mergers

Given the very high costs of mergers, why do they still occur? Most commonly, mergers increase the chances of at least one of the constituent parties to obtain legislative representation. I find that mergers are more likely if the total popular support of constituent parties is somewhat lower or higher than the threshold required for gaining seats in parliament. Thus, under the PR or mixed electoral system where few percentage points are usually enough to assure legislative seats, mergers are more likely between small or very small parties. For example, after running as an electoral alliance in Germany’s 2005 federal election, the Party of Democratic Socialism (PDS) and the Electoral Alternative for Labour and Justice (WASG) merged in 2007 to form the Left Party. None of the parties was certain of their ability to win seats independently given that their combined support of 8.7 percent was less than the double of the 5 percent national threshold required for representation in the PR tier under the Germany’s electoral system. Under the plurality system, where electoral thresholds are higher, mergers are more likely under medium-sized ‘third parties’. For example, in the UK, the combined electoral support of the Liberal and Social Democratic parties in the last (1987) general election prior to their merger was 22.6 percent.

Additionally, the increase in size can also improve the bargaining position of constituent parties in the formation of government coalitions. Building on the recent work by Laver and Benoit, I argue that some mergers are motivated by the goal to establish one of the two or three parties of most importance for forming majority governments. This goal is achieved when the merged party is one of the two largest parties, and only these two parties can form a two-party majority coalition, or when the merged party is one of the three largest parties, and all two-party majority coalitions can be formed only among these parties. The first scenario is illustrated by the recent merger between the National Liberal and Democratic Liberal Parties in Romania, which aimed at founding a major centre-right party that could successfully compete with the Social Democratic Party as an equal. The merger between the Socialist and Social Democratic Parties in Italy in 1966 illustrates the second scenario. The two centre-left parties sought to create the ‘third force’ in Italian politics, a party that would have undermined the dominance of the largest party – the Christian Democracy – by being able to form a majority government with either it or the second-largest party, the Italian Communist Party.

At the same, my research does not support the notion that mergers could help parties to increase their chances to enter government in other ways. Specifically, I find little evidence that mergers aim to form majority parties, strongly dominant parties (defined as the largest party that can form a two-party majority coalition with either the second- or the third-largest largest party while the latter two can not form a winning coalition) or parties with the highest share of legislative seats. Thus, as a general rule, party mergers do not seem to make government formation process less competitive.

Implications for the future of party politics

One of the most important implications of these findings is that the number of mergers is likely to increase somewhat in many advanced democracies. The electoral decline of some established parties in the wake of the financial crisis should make their political elites more willing to participate in ‘marriages of convenience’ in order to assure their political careers. At the same time the increasingly successful new or young parties are less constrained by their ideologies and identities to be partners in such marriages. The on-going negotiations over the collaboration between the much-diminished Panhellenic Socialist Movement (PASOK) and the new party To Potami in Greece could be an indication of events to come in many Western European countries with previously stable parties. Such developments would bring these party systems closer to those in younger democracies in Central and Eastern Europe, where party change, having decreased somewhat in the 1990s, remains a crucial factor in party politics.

—

This article is based on Ibenskas, R: ‘Marriages of Convenience: Explaining Party Mergers in Europe, Journal of Politics, 2016 78 (2): 343–356).’ It gives the views of the author, and not the position Democratic Audit UK, nor of the London School of Economics. Please read our comments policy before commenting.

—

Dr Raimondas Ibenskas is Lecturer in Politics at the University of Southampton.

Dr Raimondas Ibenskas is Lecturer in Politics at the University of Southampton.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

The number of party mergers is likely to increase in advanced democracies https://t.co/wrlHofd7rG

The number of party mergers is likely to increase in advanced democracies https://t.co/sre7G4Bfvu

8

The number of party mergers is likely to increase in advanced democracies https://t.co/DWzymPHVKB

The number of party mergers is likely to increase in advanced democracies https://t.co/XMKM3xHLou

The number of party mergers is likely to increase in advanced democracies https://t.co/KibetXZUdP

A history of mergers b/w #PoliticalParties in #Europe via @democraticaudit https://t.co/Kt4aYGRfol https://t.co/bXroGXbflg

The number of party mergers is likely to increase in advanced democracies https://t.co/ypyx0cgqQh

Electoral decline of mainstream parties should make them more willing to participate in ‘marriages of convenience’. https://t.co/Wd5tSrz0nT

The number of party mergers is likely to increase in advanced democracies, says Dr R Ibenskas: https://t.co/2t7aE71EsA

@democraticaudit

The number of party mergers is likely to increase in advanced democracies – Democratic Audit UK https://t.co/VihoRHXkgm

The number of party mergers is likely to increase in advanced democracies – Democratic Audit UK https://t.co/XhnBrzkuKe

The number of party mergers is likely to increase in advanced democracies https://t.co/oNO6SMjT0V https://t.co/aq8TuPtcxC