It is surprisingly difficult to convince voters of partisan conspiracy theories

The United States is the place to go for conspiracy theories, with older controversies surrounding the assasination of John F. Kennedy and the mood landing giving way to the ‘9/11 was an inside job’ tendency and more recently the supposed deception around Barack Obama’s birth certificate. Here, Joseph Uscinski takes a look at ‘partisan’ conspiracy theories in the United States, and finds that in order to buy into a partisan conspiracy theory, one needs to be both inclined to believe in conspiracy theories and have partisan inclinations that match the logic of the particular conspiracy theory, making it difficult to convince a huge swathe of voters.

Credit: brownpau, CC BY 2.0

Recent studies show that conspiratorial beliefs are not only common, but that most Americans believe in one conspiracy theory or another. For example, about 25 percent believe in some form of the “Birther” theory – that President Obama is hiding his true place of origin; and an equal number believe the “Truther” theory – that President Bush orchestrated or knew in advance about the 9/11 attacks. These beliefs appear sincere.

The Ebola scare in 2014 drove some to believe that Ebola zombies were rising from the grave and were part of a government plot to depopulate the planet. In 2015, some Texans were concerned that a nearby military training exercise known as Jade Helm was actually the beginning of a federal government takeover. More recently, the death of Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia drove many to believe that President Obama had plotted his death to take control of the Supreme Court. Why do so many Americans believe in conspiracy theories?

It’s important to understand why these theories develop and spread because such beliefs may help explain subsequent negative political outcomes. Researchers have shown that conspiratorial beliefs lead to lower levels of trust in government, lower levels of political efficacy, and lower levels of voting, donating, and volunteering. Sometimes, these beliefs even lead to violence. For example, FBI agents recently arrests a man, Samy Mohamed Hamzeh, for conspiring to kill upwards of 30 people at a Freemason temple in Milwaukee, Wisconsin. He believed the Masons were the ones conspiring against the rest of us.

Aside from this, conspiracy theories can sometimes frustrate democratic government. Democracies function best when well-informed voters make rational decisions. If a significant portion of voters make decisions based upon erroneous conspiracy-driven beliefs, then all suffer the consequences. Given the large numbers of people who believe in specific conspiracy theories, as well as the amount of conspiracy theorising done on the internet, the democratic consequences of conspiracy theorising is of particular concern to us. This is why my co-authors, Casey Klofstad and Matthew Atkinson, and I, endeavoured to better understand why people choose to believe in, or ignore conspiracy theories.

Our study, “What Drives Conspiratorial Beliefs? The Role of Informational Cues and Predispositions,” recently published in Political Research Quarterly, seeks to better understand why, when presented with a cue that a conspiracy might be taking place, people choose to adopt the conspiracy theory or ignore the cue and not believe in the conspiracy theory. More specifically, we wanted to know the conditions under which information suggesting a conspiracy led people to believe in that conspiracy theory. Rather than conceiving of conspiracy theories either as psychopathologies or as the vile excrescence of modernity, we argue that conspiracy theories are adopted much in the same way that other beliefs are adopted: as a combination of new information with existing predispositions which help people interpret that new information. What role do people’s underlying predispositions play in the acceptance of conspiracy theories?

While many people are concerned that the amount of conspiracy theories floating around in the Internet can induce people to believe in those conspiracy theories, in our study, we tested the idea that belief in a conspiracy theory depended not only on exposure to information suggesting a conspiracy, but also on two other factors:

- the political cues associated with that information vis-à-vis each individual’s political predispositions, and;

- each individual’s predisposition towards seeing the world in conspiratorial terms.

We tested this proposition using a two-wave national survey fielded in the weeks prior to the 2012 presidential election, and then in the weeks shortly following. In the first wave, we measured respondents’ party affiliation. They first indicated whether they were a Democrat, Republican, or Independent, then they indicated how strongly they felt about their respective party. We also measured how much conspiracy thinking affected respondents’ worldview. Respondents agreed or disagreed with four statements such as: “Big events like wars, the current recession, and the outcomes of elections are controlled by small groups of people who are working in secret against the rest of us.” These responses were used to create a summary measure of each respondents’ level of conspiratorial thinking. As an aside, those who scored more highly on this scale were less likely to trust government or vote, and more likely to believe certain groups, such as “communists and socialists” were out to get them. Also, conspiracy thinking appears orthogonal to partisanship.

In the second wave of the survey, we examined how conspiratorial and partisan predispositions affected the reception of an informational cue suggesting the existence of a conspiracy by embedding an experiment in the questionnaire. Respondents were randomly assigned to either receive or not receive a one word informational cue, the word conspiracy, suggesting that a conspiracy was afoot. To incorporate an overtly partisan element into the design, we focused the experiment on perceptions of media bias. In the United States, Republicans have long believed that the media is biased to the left.

In our experiment, respondents were first asked: “The media coverage in the lead up to the election was the subject of much discussion. Many believed that the media was biased due to [a conspiracy/poor journalism]. Do you believe the media was biased in favor of one of the presidential candidates?” Respondents could answer “yes,” “no,” or “don’t know.” If the respondent chose “yes,” they were asked a follow-up question” “What factor do you think most likely caused biased media coverage?” Respondents could select “conspiracy” or “poor journalism.” The experimental manipulation is very subtle, simply substituting the word “conspiracy” for the phrase “poor journalism.” We did this because the cue suggesting a conspiracy, conspiracy, directly indicates a conspiracy was afoot, and requires little interpretation.

Our findings were quite telling. First, Republicans were the most likely to believe in the media conspiracy followed by Independents and Democrats. This is likely because Republicans have for decades been told by their elites that the media is biased and potentially corrupt. Second, high levels of conspiratorial thinking on the part of respondents increased the likelihood that they would believe in the media conspiracy. This trend was evident across Republicans, Democrats, and Independents. Third, conspiratorial predispositions had the strongest impact on Democrats and the weakest on Republicans. This is because messages from Republican elites have long driven belief in media conspiracy theories, without much room for conspiratorial predispositions to exert an influence. Democrats on the other hand are generally more trusting of the media, and therefore willing to believe in a media conspiracy only when they are highly conspiratorial. To put this another way, Republicans believe in media conspiracy theories largely because they are Republicans, and not so much because they are prone to conspiratorial thinking.

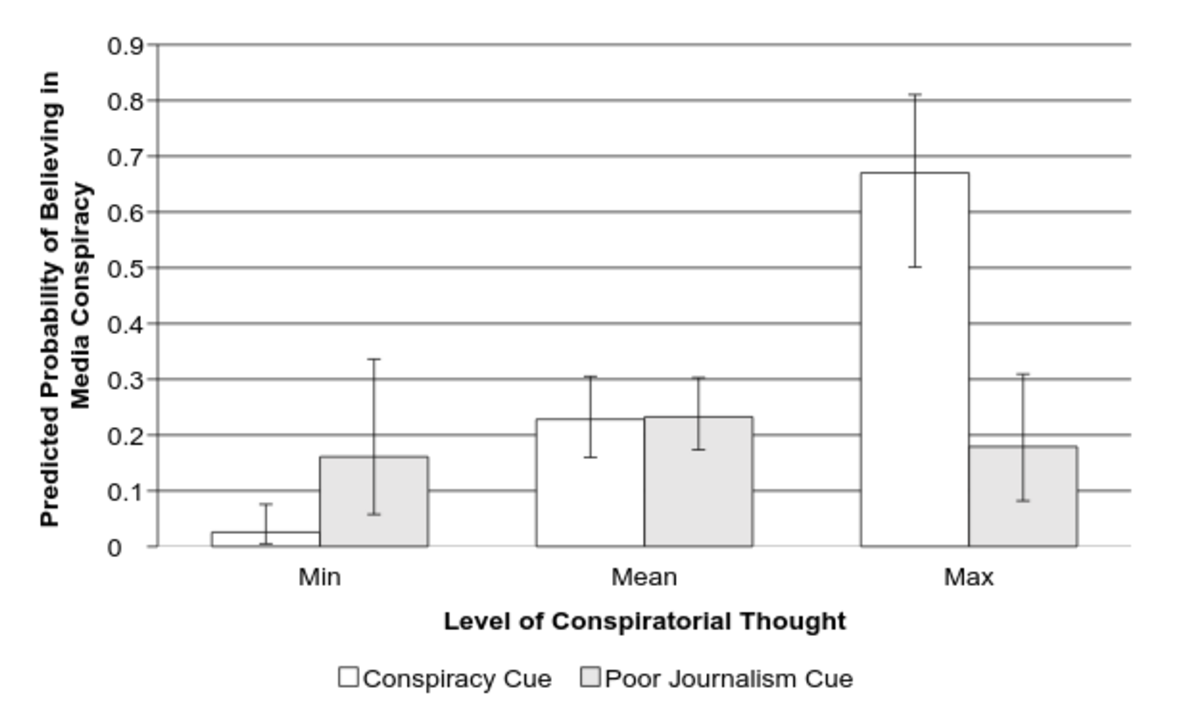

The figure below demonstrates this trend in greater detail. Looking only at non-partisans (people who when asked about their partisanship answered Independent, “not sure,” or “other”), we find that only those individuals with weak partisan priors and strong conspiratorial priors were responsive to the suggestion that a media conspiracy was afoot during the 2012 election. The right-hand side of the figure indicates that non-partisans with strong conspiratorial views were significantly more likely to believe the media bias conspiracy if they were exposed to the conspiracy cue treatment. This was the only group that was affected by the conspiracy cue.

Figure: Predicted probability of believing in media conspiracy and level of conspiratorial thought

Rather than being easy to convince people that a conspiracy is afoot, it appears somewhat difficult. People who already believe in a conspiracy theory will not be affected by new information, and neither will people who are otherwise inclined to not believe it. This seems to explain why most conspiracy theories either don’t amass many followers or run into a ceiling. In the US, partisan conspiracy theories can’t seem to convince more than 25 percent of the population. Why? Because in order to buy into a partisan conspiracy theory, one needs to be both inclined to believe in conspiracy theories and have partisan inclinations that match the logic of the particular conspiracy theory. Birther theories could not convince the non-conspiratorial or Democrats; Truther theories had a tough time the non-conspiratorial and Republicans. While many are concerned over the Internet’s ability to spread conspiracy theories very quickly and to larger audiences than ever before, most people are fickle with their beliefs and aren’t quick to fall prey to conspiracy theories.

—

Note: this post represents the views of the author and not those of Democratic Audit UK or the LSE. Please read our comments policy before posting.

—

Joseph Uscinski is Associate Professor of Political Science at University of Miami, College of Arts & Sciences, Coral Gables, FL. He is the co-author, along with Joseph M. Parent, of American Conspiracy Theories (Oxford University Press, 2014).

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

It is surprisingly difficult to convince voters of partisan conspiracy theories https://t.co/SPNSsgrQVt

It is surprisingly difficult to convince voters of partisan conspiracy theories https://t.co/VSU3l0bfcm

It is surprisingly difficult to convince voters of partisan conspiracy theories https://t.co/IG0auvbxI3

It is surprisingly difficult to convince voters of partisan conspiracy theories https://t.co/LsmE7mB9CX

It is surprisingly difficult to convince voters of partisan conspiracy theories https://t.co/xecFo8O8q2

It is surprisingly difficult to convince voters of partisan conspiracy theories https://t.co/QjtQvQyEh1

It is surprisingly difficult to convince voters of partisan conspiracy theories https://t.co/73exQBY4ev https://t.co/dQBT9na5Y3