Without supportive measures the minimum wage increase will do little to reduce inequality in the UK

National minimum wage increases over the next four years are – on their own – unlikely to solve the escalating inequality in the UK, or the widening gap between business owners and wage-earners. Teemu Alexander Puutio writes that more ambitious measures are needed, and suggests that shareholder ownership plans could offer a private-sector driven and sustainable tool even if the government is unwilling to adopt more robust policies to address inequality.

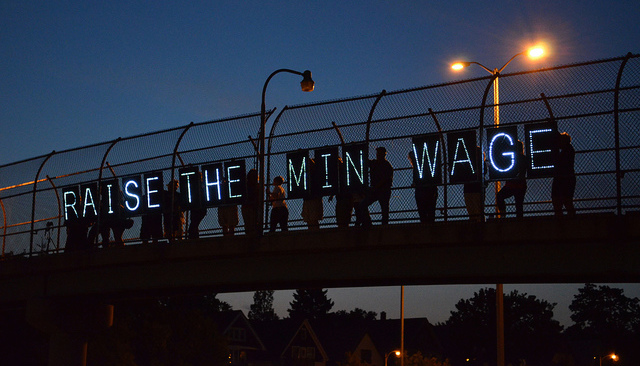

Credit: Wisconsin Jobs Now CC BY-NC 2.0

This month the national living wage for workers aged 25 and older will rise to £7.20 an hour. Should the government follow through with its current ambitions, the rate will see further increases in the years to come, and by 2020 the compulsory minimum hourly wage will be hiked to £9.00 nationwide. While some fear that the minimum wage will cause unemployment by incentivising both immigration and the substitution of labour with technology, few openly oppose the government’s aims to ensure that work pays and to widen the distribution of gains from growth. The debates over productivity, unemployment and other tangible economic facts will undoubtedly grow louder as April draws closer. The policy’s true litmus test won’t be found among the results of these debates however. Rather, it will be in the policy’s effects on long-term inequality.

With formerly obscure French comparative economists such as Thomas Piketty topping national best-seller lists and the streets of major cities being intermittently occupied by the disgruntled 99%, growing inequality has been hard to ignore. Sadly, attention has proven to be a poor substitute for action. Since the global zeitgeist turned against inequality, wealth disparities in the UK continued to grow: today the wealthiest 10% owns 875 times more than the bottom 10%, accounting for almost half of total household wealth and representing an increase of 21% from 2012. At the same time the wage share of income has diminished, and it is now at 56%, lower than the average during previous growth periods during the 1940–1980’s.

Many warn of even darker skies ahead of wage earners. If the oracles of mount Davos are to be believed, we are destined to enter the fourth industrial revolution where routine work – and even traditionally knowledge-intensive labour such as accounting and legal support – will be taken care of by machines. The returns to capital will grow while those of labour will decrease, benefiting the ownership with low-skilled workers bearing the brunt of mankind’s progress. Should these prophecies turn into reality, the upcoming living wage increase will not be enough to turn the growing tides of inequality on its own. Indeed, in making the relative losers of the next generation, the size of salary slips will matter much less than the thickness of share portfolios.

The stickiness of wages and the inevitability of inflation have surely played a role in intensifying the sting of inequality over the past decades. There have been other, less well understood, forces in motion as well. Between 1998 to 2012, the relative ownership share of private individuals declined by 36% with an absolute drop of £63.6 billion in market value. Pension funds fared even worse with a decline of 78% in their relative share and a steep £243 billion decrease in the amount owned. On the other side of the equation are investment trusts and banks that saw significant increases of 30% and 216% respectively.

Why the ownership of private business in the UK has gravitated so quickly to the hands of the few is a puzzle that vexes many. However, declining profitability and a consequent drop in the share of generally risk-averse individual investors and pension funds can be safely ruled out as an explanation. Indeed, the net rate of quarterly returns for private non-financial corporations has been growing and was recently estimated at 12.9% with the same figure for service companies reaching 23.3% – the highest estimate produced since the ONS began tabulating the data in 1997.

The widening gap between owners and wage-earners impels us to urgently reassess the distribution of ownership. The need for reassessment is particularly pressing in countries such as the UK where the relative price of labour is already high and technology is easily accessible. Solving inequality requires level-headed discussions and evidence-based policies around politically contentious issues, such as the redistribution of income and the predistribution of wealth. Taking the political reality of 2016 into account, one would be forgiven for expecting little more than lukewarm compromises and inaction from politicians however. Luckily, revising ownership arrangements is not the sole domain of crown and government.

One private-sector driven solution that has been gaining ground in the past years is the establishment of employee share ownership plans (ESOPs) that remunerate workers via stocks in addition to salaries. In 2015, 11,460 UK companies had one or more tax-advantaged scheme for remunerating employees through ownership stakes, an increase of 122 % since 2000. The growing popularity of ESOPs is attributed to how the plans make good business sense – according to a burgeoning body of research, ESOPs deliver higher productivity, enhanced profitability and strengthen employee loyalty among several other benefits. Remuneration through ownership does not raise the costs of production, leaving complex competitiveness considerations out of the equation. More importantly, ESOPs do not cause market disruptions in the way taxation and redistribution are wont to do, and thus should pose less political predicaments than other means of reducing inequality.

The rise of ESOPs has not favoured all employees equally. 9,860 of the ESOPs currently active in the UK are so called discretionary Enterprise Management Incentive programmes, which serve the management of smaller companies. The amount of plans that benefit all levels of employees, namely the Save As You Earn and Share Incentives Plans, were operational in only 1,380 businesses in 2015. What is worse, there are less all-employee schemes now than in 2000 – a stark contrast to the triple digit growth in plans benefitting the management.

Even the all-employee plans are far from panaceas. In complex organisations in particular, share ownership plans can impose significant costs, partially muting the benefits of the schemes as overheads both eat into profits and discourage expansion and further development of the plans. On the side of the employees, coupling remuneration with market performance entails increased uncertainty and risk. ESOPs also intensify the sting of bankruptcies, which threaten to wipe out both accumulated wealth and the main source of income. Finally, ownership does not mean that employees necessarily have a say in running the company. Contrary to popular opinion, emerging research shows that ESOPs and cooperative businesses à la John Lewis often fall short of democratising workplaces.

Shortcomings aside, ESOPs offer a private-sector driven and sustainable tool to reduce inequality. The government seems well cognizant of this fact. With the Finance Bill 2016 the government is taking decisive strides to improve the appeal and efficacy of ESOPs, e.g. by broadening the scope of Share Incentive Plans and revising certain tax rules, which formerly comprised some of the most complex areas of UK tax legislation.

Even more could be done. To begin with, capital gains taxation could be made progressive so that ESOPs become even more beneficial in the lowest ends of the wealth spectrum. A possible follow-up would be to make all-employee ESOPs mandatory for every company that offers options or share programmes to higher-level management. Without bold business sector reforms minimum wage increases will provide temporary relief at best. Coupled with diverse and equitable ownership arrangements, minimum wage increases could then be the stepping stone to a future where growing rates of inequality are read off the pages of history books rather than front-page news.

—

This post represents the views of the author and not those of Democratic Audit UK. Please read our comments policy before posting.

—

Teemu Alexander Puutio is Assistant Economic Affairs Officer at the United Nations Economic and Social Commission for the Asia and the Pacific where he supports regional member states on several aspects of economics and law. Teemu’s current Ph.D. and degree studies at University of Turku and London School of Economics and Political Science involve assessing the complex interplay between good governance and international law including in areas such as corporate finance financial markets. The current article represents preliminary results of an ongoing study of impacts of the separation of ownership and control.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

[…] post was originally posted on Democratic Audit UK. About the […]

Without supportive measures the minimum wage increase will do little to reduce inequality in the UK https://t.co/NiexztA2Ds

Without supportive measures the minimum wage increase will do little to reduce inequality in the UK https://t.co/1vJjk21svn

Without supportive measures, the minimum wage increase will do little to reduce inequality in the UK https://t.co/SooCUDLqrt

Without supportive measures the minimum wage increase will do little to reduce inequality in the UK https://t.co/PN2PwSmbo4

Without supportive measures, the minimum wage increase will do little to reduce inequality in the UK https://t.co/BHtmxD0hLa

“ESOPs deliver higher productivity, enhanced profitability and strengthen employee loyalty among several other benefits.”

Climate change is a greater threat to humanity than inequality. Higher productivity from ESOPs make climate change worse

Higher labour productivity means higher production. Higher production means higher consumption, which almost certainly means more greenhouse gas emissions. These will bring on climate disaster. To support the poor redistribution is needed – from the polluters (the affluent) to those that pollute less (the poor).

More detail…

It is possible to improve production so that it emits less greenhouse gasses for each unit of production. e.g. it is possible to change manufacturing techniques and energy generation so that making a car or building a house emits less greenhouse gasses than it did last year. This measure is called the carbon intensity of production. (“Carbon intensity” because greenhouse gasses are measured in relation to the main GHG, carbon dioxide.)

The rate of change of greenhouse gas emissions increases with the rate of economic growth. It decreases if carbon intensity is decreased. The problem is that when the world has emitted a certain amount a limit is reached and climate disaster happens. To keep within this limit in the coming decades means decreasing emissions extremely fast – at a rate that cannot be achieved without decreasing output as well as its carbon intensity. We need to decrease carbon intensity, production and consumption. i.e. de-growth.

See “Jobs and climate change” (https://ow.ly/1081WS )

Without supportive measures the minimum wage increase will do little to reduce inequality… https://t.co/2ruKuDPtub https://t.co/lM9Kuduv1k