Citizen assessment of the political system is fostered by rational considerations rather than virtuousness

Scholars have often assumed that citizens value fairness with respect to the inclusion and representation of different groups in the electoral process, and therefore are likely to favour proportional over majoritarian systems. However, in a recent study Benjamin Ferland found that citizens actually prefer their party to be advantaged at the expense of others, indicating citizen satisfaction with the political system is shaped more by rational considerations than by virtuousness.

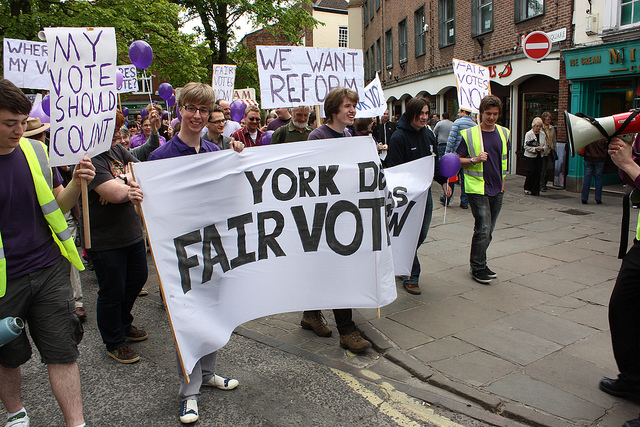

Do citizens value fairness in the electoral competition? This is a central question that has interested scholars over the last decade. As claimed recurrently in the debate about the reform of the electoral system in Canada and in Great Britain, proportional electoral systems favour a more accurate translation of votes into seats while majoritarian systems have the tendency to “waste” the votes of many citizens. Inter alia, therefore, PR electoral systems have the benefit of representing the voice of more citizens in legislatures and in the policy-making process. Implicitly, scholars have often assumed that citizens also share and even support this view of inclusiveness in the democratic process. Scholars have thus depicted a virtuous citizenry who value fairness with respect to the inclusion and representation of different groups in electoral competition. Well, is it really the case?

A simple way to address this question is to examine whether citizens are more satisfied with the functioning of their political system and the democratic process when electoral rules translate votes proportionally into seats. The fact of observing an increase in citizens’ satisfaction as the proportionality of an electoral system increases would be an indication that citizens value fairness in the electoral competition.

What is puzzling, however, is that empirical results until now do not support such view. The relationship between a proportional votes-seats translation at elections and citizens evaluating positively the functioning of their democracy is at best tenuous. Why do we observe this disconnection between our normative expectations of inclusion and diversity in legislatures and such null empirical findings? Furthermore, if citizens do not value fairness in the electoral competition, why might this be?

Politics as a competition between groups

A different approach is to conceive the democratic process, and elections in particular, as a competition between different groups, which want to influence the allocation of political and economic resources in society. In casting a vote, we should keep in mind that a citizen participates in this resource allocation by favouring one party over the others. This view of electoral politics is consistent with recent studies on turnout showing that voters’ affinity with their partisan group (how much they like their party) and antipathy toward the other partisan groups (how much they dislike the other parties) make them more likely to vote at elections. Through experimental research design, these studies also show that people tend to favour supporters of their partisan group (over non-supporters) when distributing a given some of money. Overall, if we accept this view of electoral politics, our assumption about how electoral systems and especially the votes-seats translation may affect citizens’ assessment of their political system may be revised. From this perspective, instead of valuing fairness in the electoral competition, citizens should want their party to be advantaged in the electoral competition and the other parties to be disadvantaged. In other words, a citizen should prefer her party to receive a greater share of seats than votes and the other parties to receive a smaller proportion of seats than votes.

At a first glance, this assumption may fit well with current patterns in majoritarian electoral systems where voters winning their election are generally those that are advantaged by electoral rules. As shown in many studies, citizens tend to be more satisfied with the political system when they win elections. Should we, however, expect the same relationship to hold under PR electoral systems? I believe that it is the case. Even if being advantaged by electoral rules has fewer implications in terms of winning/losing in PR electoral systems it may still have significant implications for a party’s influence in the policy-making process – whether the party is in opposition or in cabinet. If the party is in government, it may receive a greater share of cabinet portfolios given that these are generally attributed correspondingly to each party’s seat share in the legislature. If the party is in opposition, it may still have a greater influence in the policy-making process given that the government is generally more “open” to opposition parties in PR electoral systems.

The findings

In order to test the validity of these assumptions, I use survey data from the Comparative Study of Electoral Systems in 15 advanced industrial democracies over the 1996-2011 period. Through advanced statistical analyses, I find that citizens indeed prefer their party to be advantaged (and other parties to be disadvantaged) in the electoral competition under both majoritarian and PR electoral systems. The relationship is in fact even greater under PR systems when controlling for whether a voter’s party has won or not the election. I also find the relationship to be greater as a voter’s level of affinity toward her party and antipathy toward the other parties increases.

Implications for reforms of the electoral system

The findings have important implications for electoral reforms. While citizens supported the adoption of a mixed member proportional electoral system in New Zealand in 1993, electoral reform to introduce an aspect of proportionality has failed in three Canadian provinces in the last decade. One of the reasons that may explain this negative outcome is the fact that many citizens are actually advantaged by the current majoritarian electoral rules. Indeed, it is often only the minor parties that are disadvantaged in the electoral competition. Moreover, the results may explain why citizens’ assessment of their political system is generally similar across majoritarian and PR electoral systems even if we observe greater levels of votes-seats proportionality in PR systems.

Overall, the findings are consistent with a conception of politics as a setting where groups are in competition with each other and where citizens – also actors of this competition – prefer their group to be advantaged in the electoral results – to the detriment of other groups. While politicians and scholars generally agree with the fact that different voices in society should be represented in the democratic process it seems, however, that citizens do not share this perspective – at least to the same degree. In the end, my conclusion is that citizens’ assessment of the political system is fostered by rational considerations rather than virtuousness.

—

Note: this post represents the views of the authors and not those of Democratic Audit UK or the LSE. Please read our comments policy before posting.

—

Benjamin Ferland is a Post-Doctoral Scholar in Political Science at Pennsylvania State University

Benjamin Ferland is a Post-Doctoral Scholar in Political Science at Pennsylvania State University

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Citizen assessment of the political system is fostered by rational considerations rather than virtuousness https://t.co/6sDjnAGBuV

Citizen assessment of the political system is fostered by rational considerations rather than virtuousness https://t.co/uOTz2stpHG

Citizen assessment of the political system is fostered by rational considerations rather than virtuousness https://t.co/0cigWd61mf

Do citizens prefer their party to be advantaged at the expense of others? @ferland_ben uses CSES in @democraticaudit https://t.co/Y7GLSFBjqS

Citizen assessment of the political system is fostered by rational considerations rather than virtuousness https://t.co/AtCu43HB2t

Citizen assessment of the political system is fostered by rational considerations rather than virtuousness https://t.co/JUMhyFRnN8

@UDLdn @ElectSystProj thanks for flagging – link here https://t.co/Ucbn0gc0SH

Do citizens value fairness in the electoral competition? Well, not as we might think! https://t.co/VWw8hkpl6O

Can’t speak to the validity of the analysis here, since we don’t see it. However, a couple of things don’t ring true. First of all, we know that Arend Lijphart’s comparative studies of voting systems found significantly greater voter satisfaction with government and politicians in countries with proportional voting. And since when is partisanship rational? Yes, winners prefer the existing system (the Catch-22 of electoral reform), but under the first-past-the-post voting, most of us are losers. Most of us vote for people who don’t get elected, and we end up with a government that most of us voted against. And that’s why we hate politicians. “Virtuousness” and “rational considerations” are not opposites. The article should be titled “Citizen assessment of the political system is fostered by irrational considerations.” And since when do “politicians and scholars generally agree” on anything?

Voters, according to this, prefer an electoral system that benefits the party they support, not one that is fair. https://t.co/XE3bDYxlda

Citizen assessment of the political system is fostered by rational considerations rather… https://t.co/Ucbn0gc0SH https://t.co/YFyTDwcMLG

@democraticaudit Evidence supporting PR benefits is strong. https://t.co/jnEOaNJbHw Need better messaging? https://t.co/0O1ihc9N13