Learning the lessons: What other referendums can teach us about the EU vote

While we’re nowhere near Switzerland or California in constantly using referendums, the UK is becoming accustomed to big constitutional votes. Katie Ghose discusses what the AV and Scottish referendums tell us about the likely shape of the EU debate.

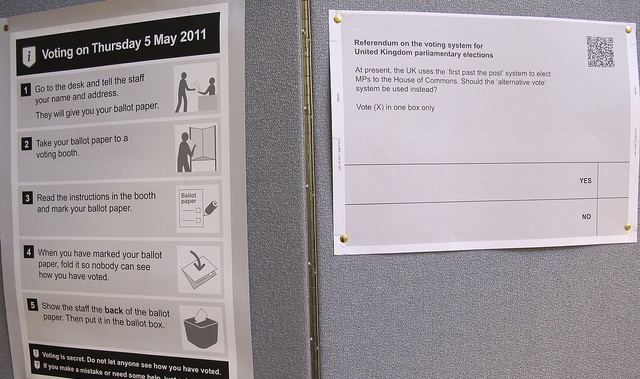

Credit: Rain Rabbit CC BY-NC 2.0

In 2011, the ballot on switching to the Alternative Vote was only the second UK-wide referendum – the first being the vote on membership of the European Economic Community (EEC) in 1975. That was followed by referendums in 1997 leading to establishment of Scottish Parliament and Welsh Assembly (with a Yes vote to further Welsh powers in 2011).

Then came the Scottish independence referendum campaign, which lasted for two years – culminating in a vote on 18 September 2014. It offers a stark contrast with the EU referendum – which, following a ‘phony war’ whilst the Prime Minister carried out negotiations with other EU nations, was only formally launched four months before polling day.

But what do recent referendums in the UK and elsewhere tell us about the likely shape of the EU debate?

Referendums find favour with fans of direct democracy for giving over decisions to the public – yet they are actually quite conservative instruments, with voters reluctant to stray from the status quo. This is exploited by the ‘Stay as it is’ camp who stress the cost, complexity and scariness of the unknown – whether that’s a new voting system, moving from monarchy to republic or full-blown independence for Scotland. It is notable then, that the Out campaign are already fighting back, claiming that staying in brings as many uncertainties as exit.

As claim meets counter-claim, separating fact from fiction or wild exaggeration from realistic prospect becomes virtually impossible, and into this comes the importance of party cues.

Signals sent by trusted politicians help voters to shortcut a mass of information – or nudge them to one or other position. While Labour supporters can fairly reliably turn to their party for a Remain cue, Conservative party opinion is more divided. The EU campaign exploded into life last week when the Prime Minister and Boris Johnson took opposing sides – strongly indicating that in this campaign, cues will be more muddled.

The Prime Minister’s opinion will be influential for many – mirroring a muddy debate in the public eye on the issues. David Cameron reflected this back to voters, when at a public meeting this week he spoke of the time he has spent personally considering the issues in his six years as Prime Minister. But this cannot compare to the game-changing moment during AV campaign when David Cameron nailed his colours to the mast and it was game over for Yes to AV. On an issue few felt strongly about, a relatively new PM at a peak of his popularity contrasted with a deeply unpopular Deputy and a divided Labour party – factors which played strongly to his hand.

Two other referendum features are already in play. Cross-party working is common; the interest lies in where the lines are drawn, and who the unexpected bedfellows are. Yet the more intra and inter-party warfare, the easier it is for pundits and commentators to be drawn to these aspects, rather than the core arguments on the issues.

Journalists struggle to treat referendums as unique creatures, seeing them instead through the lens of everyday party politics – as evidenced by the emphasis on Boris v Dave and the implications of the referendum for the future leadership of the Conservative party. All this is identical to the speculations about what the Scottish referendum would mean for Alex Salmond and the SNP, and for Labour the electoral fall-out from sharing platforms with the Conservatives back in 2014.

Finally, whilst the influence of election campaigns is often over-played, referendum campaigns do matter. As with politicians, voters are heavily reliant on both sides for awareness-raising and opinion. Who is designated to speak up will make a difference – especially given the stark differentiation in messaging and tone among rival groups on the Exit side.

With only a few months between the referendum announcement and voting day, and every possibility of several million citizens deciding with just weeks to go, each side’s influence will be even more pronounced. Whatever the result, the UK will have another fascinating case study to add to its growing experience of nationwide public polls – for better or worse.

—

Note: The Electoral Reform Society will be releasing new polling on the EU referendum on Thursday – the first of a monthly polling series on the public’s engagement with and perception of the referendum.

The findings will mark the launch of ‘A Better Referendum’ – a campaign to get a real public debate going about the facts and issues of the EU vote, and to provide clear and balanced information on both sides in the run up to June 23rd.

This post represents the views of the authors and not those of Democratic Audit UK or the LSE. Please read our comments policy before posting.

—

Katie Ghose is Chief Executive of the Electoral Reform Society.

Katie Ghose is Chief Executive of the Electoral Reform Society.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Learning the lessons: What other referendums can teach us about the EU vote https://t.co/m9Dv0CbFKI

Learning the lessons: What other referendums can teach us about the EU vote https://t.co/pMusjsLurM

Learning the lessons: What other referendums can teach us about the EU vote https://t.co/vVoTSPYVRy

Learning the lessons: What other referendums can teach us about the EU vote https://t.co/KhTfVlJ0pd

Learning the lessons:- What other referendums can teach us about the EU vote https://t.co/H6LJuWQEzA

Learning the lessons: What other referendums can teach us about the EU vote https://t.co/8YRAaYfMj9

Learning the lessons: What other referendums can teach us about the EU vote https://t.co/sJH2YTX5wm

Learning the lessons: What other referendums can teach us about the EU vote https://t.co/oq9kWSrKua https://t.co/U9ldqqLNSA