Allowing transnational voting during European elections could alleviate the EU’s democratic deficit

European Parliament elections are often criticised for lacking the required level of voter engagement to confer democratic legitimacy to the integration process. Jonathan Bright, Diego Garzia, Joseph Lacey and Alexander Trechsel assess whether ‘transnationalising’ European elections by allowing voters to back parties in other EU countries would help alleviate the problem. They argue that language barriers may represent a challenge, but suggest that internet-based ‘voting advice applications’ could help bridge this gap and offer a more representative range of choices to national electorates.

Credit: Charles Clegg, CC BY SA 2.0

The European Union is facing one of the most challenging moments in its recent history. While the struggle for a solution to the common challenge of migration and refugees continues, the spectre of debt, recession and high unemployment continues to haunt the countries of the southern Eurozone, with the likelihood high of another round of acrimonious negotiations between creditor and debtor countries in the near future. These crises have been toxic for public perception of the EU across the union, with trust in institutions such as the European Parliament declining to record lows in recent years (though they somewhat recovered in 2015).

One common element among both of these crises is the question of whether the EU has any democratic legitimacy when making key decisions which appear to produce winners and losers among nation states. The EU’s (lack of) legitimacy as a democratic body is, of course, a classic problem in EU studies which has plagued the organisation since its inception.

A recurring theme in this debate is the failure of the European Parliament, the EU’s only directly elected institution, to establish itself in the minds of the European public as a legitimate locus of power. One of the major reasons put forth for this lack of legitimacy is the status of European Parliament elections as “second order”, being treated as a minor engagement in ongoing national political battles, rather than a major event in its own right. The lack of interest in the event is reflected by the continuously declining turnout witnessed in these elections, which stood at just over 42 per cent in the most recent poll in 2014.

In a recent study, we examine a proposal that may go some way toward addressing this problem: the ‘transnationalisation’ of European Parliament elections, which would involve allowing voters to vote for parties in any EU member state when they went to the polls (at least for a portion of seats in the parliament itself). Such a proposal could play a role in helping European elections to break free from the clutches of national politics: in particular, when campaigning, national parties would have to adjust their electoral offer to both take account of the increased competition for their ‘national’ vote and also to potentially address voters in other countries.

Of course, such a move would face significant practical challenges. Voters would be faced with around 300 major parties, most of whom would be communicating in a foreign language. To address this problem, we suggest that the election would have to be at least partially supported by a number of ‘voting advice applications’, which would allow citizens to sort through the multitude of different parties on offer. These tools have become increasingly popular and are recognised in political systems around the world.

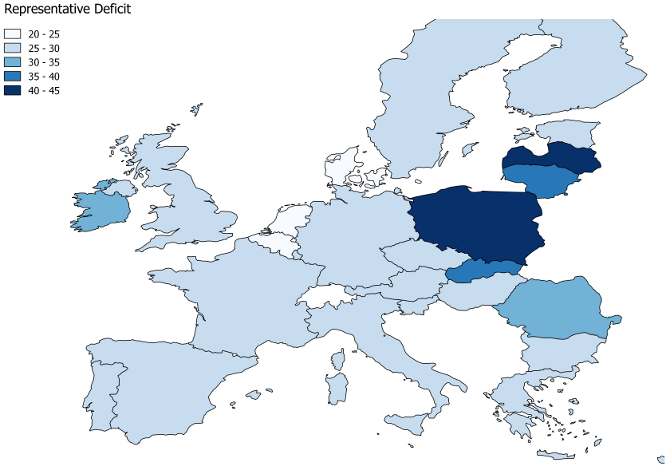

Figure: Representative deficit in different EU member states, measured as the average difference between citizens and parties in terms of policy preferences

Note: Countries with a darker colour have a greater ‘representative deficit’ than those with a lighter colour. For more information see the author’s recent article in European Union Politics.

Our article also seeks to collect evidence on the extent to which this change would be welcomed by European citizens. We do so using data gathered from the EU Profiler, a voting advice application which was created and run during the 2009 European Parliament election and which attracted hundreds of thousands of users. We would not expect everyone in Europe to want to vote for a party from another country, and our data show that these people are indeed in a minority: around 18 per cent of respondents indicated that they would be interested in doing this.

We found these people were more likely to be those who were dissatisfied with the state of their current national democracy; we also found that they were more likely to be people who could improve their representative fit by finding a party that more closely overlapped with their interests. Our data furthermore enables us to estimate the level of representative ‘deficit’ which could be found in each country, as measured by the extent to which preferences of voters are unrepresented by parties, shown in the figure above. Hence transnationalising European politics in this way would also have the added benefit of allowing people unhappy with their national politics to find better representation elsewhere.

—

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of Democratic Audit nor of the London School of Economics. It originally appeared on the LSE Europp blog. For more information on the research, see the authors’ recent article in European Union Politics. Please read our comments policy before commenting.

—

Jonathan Bright is a Research Fellow at the Oxford Internet Institute in the University of Oxford.

Diego Garzia is a Research Associate at the European Union Democracy Observatory (EUDO), European University Institute

Joseph Lacey is a Junior Research Fellow in Politics at University College, and is associated with the Department of Politics and International Relations, University of Oxford. He holds a PhD from the European University Institute and was a Fulbright Schumann awardee.

Alex Trechsel is Professor of Political Science and Head of the Department of Political and Social Sciences of the European University Institute.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Allowing transnational voting during European elections could alleviate the EU’s democratic deficit https://t.co/mmHmMvbgz5

Allowing transnational voting during European elections could alleviate the EU’s democratic deficit https://t.co/odgfV4xqNv

“Allowing transnational voting during European elections could alleviate the EU’s democratic deficit” https://t.co/YGDf8wIUC5 #democracy

Nice in theory! As you probably know, (foreign) EU nationals living in another EU country can choose to vote in their adopted EU country in the European Elections. E.g. a Spaniard living in the UK can apply to vote in EU elections in the UK. We say (in the UK at least) that they acquire the so-called ‘K’ franchise – until then they’re ‘G’ voters and they’re only eligible to vote in EU elections in their home country. When becoming a ‘K’ elector, there is supposed to be a system to prevent the elector from voting in their home country. Does it work? Does it heck! And that’s a relatively simple process compared to one you’re advocating. As I said, good in theory, but probably unworkable in practice.

The EU’s democratic deficit & potential benefits of using transnational #voting in Euro #elections https://t.co/jvhZUELovl @democraticaudit

Allowing transnational voting during European elections could alleviate the EU’s… https://t.co/erYr0MEwZe https://t.co/ClyQYStsjV